1 In 7 College Students Abuse 'Smart Drugs' To Improve Concentration, Grades

College students experience a tremendous amount of pressure, pulling all-nighters to cram for mid-terms and finals, and churning out papers after papers. To boost brain power, an increasing number of healthy students are popping pills, specifically called "smart" drugs, in order to gain an edge, and the grades they need in their classes. One in seven healthy Swiss college students have been found to enhance their cognitive performance with the use of prescription medication, legal drugs, or illegal drugs during their academic careers, according to a recent study.

Practicing what's known as neuroenhancement, on college grounds, typically refers to the use of prescription drugs or other psychoactive substances by healthy individuals who seek to fight off fatigue, and improve concentration. These stimulants are mostly used when individuals find themselves in situations where stress is placed on individual performance and the person, therefore, fears they may not excel.

Stimulant drugs such as methylphenidate and amphetamines are commonly referred to when focusing on the field of neuroenhancement. These two stimulants are often prescribed to treat individuals with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with the purpose of inducing a calm and focused effect in patients, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. But for healthy individuals, taking the drugs increases wakefulness, focus, and attention — something the students don't need help with — which makes them the drugs of choice for those who want to enhance cognitive performance. The availability of these effective drugs, and the increasing tolerance for neuroenhancement practices, may present a growing drug problem for students, especially those in college, the researchers said.

A team of Swiss researchers sought to investigate whether the prevalence of neuroenhancement drugs was similar to those in other countries, along with other relevant factors, such as study-related stress, which could induce drug abuse among college students. More than 28,000 students from three different educational institutions in Switzerland were asked to complete an online survey about the use of psychoactive substances. The final sample size of the study included over 6,000 college students.

In the study, neuroenhancement was identified as the use of prescription drugs or other psychoactive substances — cannabis, for example — to directly or indirectly enhance brain function, particularly concentration, alertness, while also reducing nervousness. Prescription drugs, alcohol, and illicit drugs taken with the intent of improving mental performance were termed “neuroenhancers.” Non-prescription drugs, food supplements, and caffeine-containing products were regarded as “soft enhancers” in the study.

In the survey, the participants were asked to rate the degree of stress and performance pressure they felt with regard to education, work, leisure, and family on a scale from one to five. The subjects were asked whether they had ever used one or more of the substances listed on the survey without having a clear medical reason for doing so, among other questions.

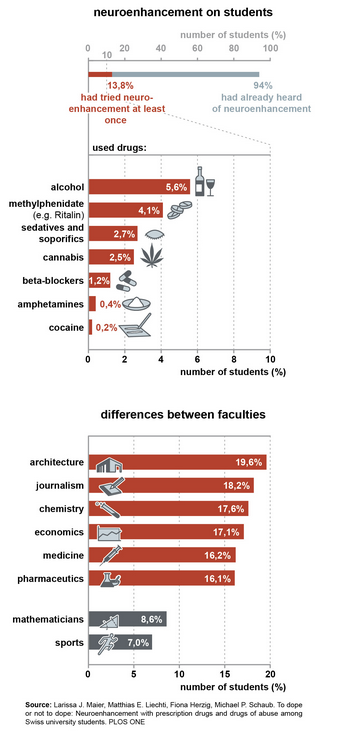

About 14 percent admitted to improving their cognitive performance with prescription medication, legal drugs, or illegal drugs at least once during their degrees. In descending order, they used Alcohol 5.6 percent of the time, followed by methylphenidate, such as Ritalin (4.1 percent); sedatives and soporifics, such as Ambien (2.7 percent); cannabis (2.5 percent), beta-blockers (1.2 percent), amphetamines, such as Adderall (0.4 percent); and cocaine (0.2 percent), according to the news release.

Students used these substances most often during examination periods, or when they felt general stress during their studies. The daily intake of neuroenhancement remained relatively low at almost two percent. Meanwhile, the majority of students were found to consume "soft enhancers" such as caffeinated products, non-prescription vitamin products, or herbal sedatives before their last big exam — with a third consuming them every day.

The use of performance-enhancing drugs was found to be most prevalent among advanced students who had jobs alongside their studies, and therefore, reported higher stress levels. The areas of study that were more likely to abuse “smart” drugs were architecture (19.6 percent), journalism (18.2 percent), chemistry (17.6 percent), economics (17.1 percent), medicine (16.2 percent), and pharmaceutics (16.1 percent), far from the level of drug-use in those who studied mathematics (8.6 percent) or were sports students (seven percent).

"The development of neuroenhancement at Swiss universities should be monitored as students constitute a high-risk group that is exposed to increased stress and performance pressure during their degrees," Michael Schaub, study leader and head of the Swiss Research Institute for Public Health and Addiction, said in the press release. "However, there is no need to intervene as yet."

The high lifetime prevalence rate of neuroenhancement found in the study is contingent with the researchers’ definition of “neuroenhancement,” which included drugs with sedative effects. This interpretation impacted their results.

In a similar study published in the Journal of American College Health, researchers found 34 percent of over 1,800 undergraduate students admitted to the illegal use of ADHD stimulants. These stimulants were typically used during periods of high academic stress. The participants saw them as a means to reduce fatigue while increasing concentration.

As college students continue to be a high-risk group for “smart” drug abuse, these studies suggest that they be closely monitored by health officials.

Sources: Herzig F., Liechti ME, Maier LJ et al. To Dope or Not to Dope: Neuroenhancement With Prescription Drugs and Drugs of Abuse Among Swiss University Students. PLOS ONE. 2013.

DeSantis AD, Noar SM and Webb EM. Illicit Use of Prescription ADHD Medications on a College Campus: A Multimethodological Approach. J Am Coll Health. 2008.