Children with Disabilities Are More Vulnerable to Abuse and Violence in the Developing World

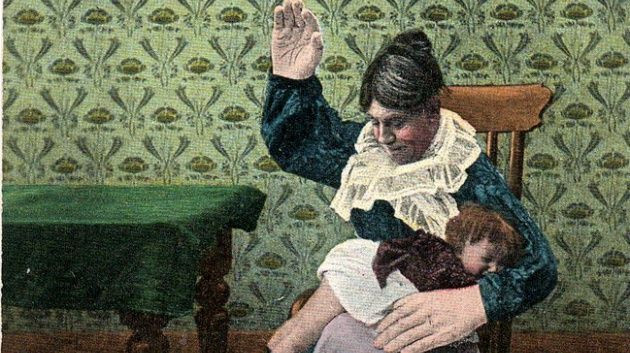

Children with disabilities in developing countries are at a greater risk of receiving harsh punishment from parents due to misconceptions about disabilities, according to a new study.

Researchers hailed from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), Duke University, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. They used data from the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF)'s Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey, which collects data to monitor conditions of children and women with the goal of providing information as a basis for policy decisions and interventions.

This was the largest study to analyze how having a form of disability can affect the type of punishments or discipline inflicted on children in developing countries. The study reviewed the use of discipline by 46,000 parents and caretakers of children between the ages of two and nine, who were living in low- and middle-income countries.

The researchers provided parents and caregivers with a questionnaire that evaluated what type of disability their children had (cognitive, language, sensory, or motor); it also asked how the parent used discipline — whether verbal, emotional, or physical aggression (spanking, hitting or beating). The results showed that children with disabilities were more likely to be physically beaten than they were to experience nonphysical discipline. This type of physical punishment was more likely to occur in poorer countries.

According to UNESCO, more than one billion people around the world — 93 million of whom are children — have some form of disability.

Interestingly, but not surprisingly, attitudes about disability vary between cultures. While in some countries, people with disabilities are stigmatized and discriminated against, in certain areas of Nepal and India, children with cognitive disabilities are seen to have divine qualities. Likewise, the Hmong people — a mountainous culture originating in China, Vietnam, and Laos — see epilepsy as a form of spiritual gift.

"The findings suggest that policies and interventions are needed to work toward the United Nations' goals of ensuring that children with disabilities are protected from harsh physical treatment and abuse," said NICHD researchers Charlene Hendricks and Marc H. Bornstein.

The United Nations states that all necessary measures should be taken to "ensure the full enjoyment by children with disabilities of all human rights and fundamental freedoms on an equal basis with other children" and that "the best interests of the child [with disabilities] shall be a primary consideration."

The researchers stressed the importance of education about disabilities, noting that if parents were better informed, they could move forward with improved ways of disciplining their kids.

"Parents may believe that children with disabilities won't respond to less harsh forms of discipline," Jessica Lansford, research professor at the Duke University Center for Child and Family Policy, told DukeToday. "Or they may be frustrated, and may not know what else to do. If that's the case, then community-level interventions could make a difference in changing community perceptions of disabilities."