The Curious Life Of Conjoined Twins: How Sharing A Body Changes The Way They Think, Drive, And Date

Conjoined twins are human anomalies. With their lives reliant on their physical connection to one another, their chances of survival are low. Despite the lack of scientific investigation on conjoined twins, medical knowledge continues to grow with each surgery, autopsy, and laboratory test. The life of a conjoined twin is complex, extraordinary, and emblematic of public intrigue, driving experts to want to pry into the intimacy of their lives and ask the questions: How do they feel, think, write, run, and engage in sexual activity?

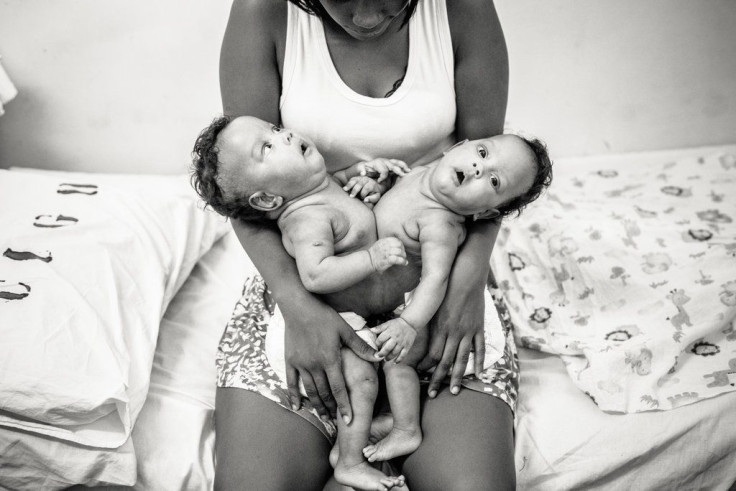

One in every 200,000 live births results in a set of conjoined twins, and their chances of survival are between just 5 and 25 percent. According to the University of Maryland Medical Center, 40 to 60 percent of conjoined twins are stillbirths, and another 35 percent only survive a day after they’re born.

Conjoined twins are born from the same egg which does not fully separate once it’s fertilized. During the first few weeks of gestation, the egg develops into an embryo that begins to split into identical twins, but the partially separated egg stops splitting and begins growing into a conjoined fetus. There are nearly a dozen different types of conjoined twins, but one of the most commonly connected twins — thoracopagus twins — are attached at the upper portion of the torso. They share a heart, making it nearly impossible to surgically separate them without one or both twins dying. Roughly 40 percent of all conjoined twins are thoracopagus.

The second most common type of conjoined twins is connected from the breastbone to the waist. In the case of omphalopagus, which makes up 33 percent of all conjoined twins, they may share a liver, gastrointestinal tract, and reproductive organs, but rarely share a heart. The rarest type of conjoined twins is connected at the head. The case of craniophagus makes up only 2 percent of conjoined twins born alive.

Experts aren’t sure why, but females are three times as likely to survive than male conjoined twins, which is why 70 percent of all living conjoined twins are females. There are fewer than 12 pairs of conjoined twins living in the world today.

If the twins are born alive against the odds, doctors use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, and angiography to determine what organs the twins share. Next, they examine the scans to weigh the possibility of separating the twins through surgery. But the procedure is highly complex and dangerous. Since the surgery was first performed in 1950, the success rate continues to promise only one twin survives separation roughly 75 percent of the time.

Sharing Life

Living life as a conjoined twin completely eliminates the possibility of true privacy. Being physically attached to your sibling via the chest, hip, or head changes the type of bodily functions they share.

Thinking And Writing

For 98 percent of all sets of conjoined twins, each person has their own separate and distinct thoughts and feelings. But in the case of a set of craniopagus twins, which occurs in only one in 2.5 million births, they share neural activity because their skulls are connected. In the case of 8-year-old Tatiana and Krista Hogan, twins born conjoined and connected at the tops of their heads, their mental processes affect each other. If one twin’s leg is touched, the other would feel it. When they write, their mind is prompted to anticipate the next word. Tatiana hates ketchup and will scream when Krista eats it.

The girls are developmentally delayed because they’re attached at the thalamus — a region of the brain that involves sensory perception and motor function. The girls are still too young to investigate their neurological wiring, but from the MRI scans, doctors have determined this “thalamic bridge” links one sister’s sensory input to the other, creating a conscious loop. Essentially, if one thinks a happy thought, the other can perceive it. When one sees an image through her eyes, the other receives the image milliseconds later.

Their pediatric neurologist Dr. Juliette Hukin, from BC Children’s Hospital, described their brain structure as “mind-blowing.”

Yet, tracing and deciphering what their neural pathways will do is still largely unknown, especially because craniopagus twins are so rare with little literature published on their brain structures and abilities.

Driving And Dressing

In the case of 25-year old Abigail “Abby” Hensel and Brittany Hensel, each twin fully controls her half of the body — one leg and one arm on either side. They are symmetric conjoined twins with normal proportions. Each twin has her own heart, stomach, spine, lungs, and spinal cord, but share a bladder, large intestine, liver, diaphragm, and reproductive organs.

Unlike Tatiana and Krista, their sense of touch is limited to their half of the body. If you touched Brittany’s arm, Abby would not feel it. But even though they have their own stomachs, if one has a stomach ache the other feels it. Since infancy, Abby and Brittany had to learn how to coordinate with one another in order to perform simple tasks, such as clapping, crawling, and eating.

As adults, they are able to eat and write separately and simultaneously without speaking with one another to execute motions. They’ve developed their own fashion style and have their own unique personalities — Abby being the outgoing sister, and Brittany the more subdued. Physical activities like running, biking, and swimming must be a joint team effort. They can also type on a keyboard at a normal rate and drive a car. However, because they’re considered two different people, they each have their own licenses. Same goes for their college degrees — each has their own certified teaching degree from Bethel University.

"I don't think there's anything that they won't try or something that they couldn't be able to do if they really wanted to," said Paul Good, principal of the school where Abby and Brittany work. "To bring that to children, especially kids who might be struggling, that's very special. That's learnt through lived example."

Sex And Dating

This sensitive subject has rarely been investigated because, perhaps unsurprisingly, these questions are highly private and complex. There aren’t enough adult sets of conjoined twins to conduct a study with a large enough population, and even if they did, it’s a conflicting topic to broach. People — whether conjoined or not — tend to keep their sex lives intimately their own. Yet that doesn’t stop the public from inquiring.

In cases when twins are good candidates for surgical separation, doctors sometimes discuss the opportunity to have private sex lives as a motivation. If they are biologically unable to be separated without running the risk of losing one or both of the twins, the question of their sex lives will continue to remain largely unanswered. If one twin is sexually stimulated, does the other feel it? Of course, it depends on their body structure, but regardless of whether or not they share genitals, arousal releases hormones into the bloodstream and all twins share a circulatory system. Without evidential research, we are left to speculate.

Bioethicist Alice Dreger, a professor at Northwestern University and expert on conjoined twins, shines some light on this dimly lit subject:

“Although there are no real studies of the sex lives of conjoined twins, we can safely assume that conjoined twins want — and occasionally feel conflicted about wanting — sex, as we all do. Conjoined twins simply may not need sex-romance partners as much as the rest of us do. Throughout time and space, they have described their condition as something like being attached to a soul mate. They may just not desperately need a third, just as most of us with a second to whom we are very attached don’t need a third — even when the sex gets old.”

But even if they have their soul mate by their side, conjoined twins have a history of seeking out a partner outside of their siblinghood. When Millie and Christina McCoy were born in North Carolina in 1851, doctors discussed whether the conjoined twins could marry. But they quickly concluded: "Physically there are no serious objections, but morally there was a most decided one.” They were kidnapped and brought to England by an exhibitor who advertised them as one girl with two heads. Instead of continuing a discussion on their rights, the girls were objectified and taught to sing, dance, and play musical instruments in front of crowds.

In a similar circumstance, Violet and Daisy Hilton were sold as an exhibition at carnivals and fairs at the age of three. In 1931, the 23-year-old twins won a battle for their freedom against the show’s owner. Violet became the first to attempt the marital feat when she applied for a marriage license. She was repeatedly refused, demonstrating the public’s outward objection to such a union. But by 1941, Daisy’s marriage to a dancer named Harold Estep was recognized as legal.

"Mentally we have found a way to live separate and private lives, but it's almost impossible to convince other people of that,” Daisy said following the marriage approval. “We were denied marriage licenses in twenty-seven different states because they saw it as bigamy. All our lives we've had to bury every normal emotion. I'm not a machine; I'm a woman. I should have the right to live like one."