Does Music Make You Smarter? Brain Imaging Technology Says Yes, In More Ways Than One

Music teachers everywhere are going to print this out and read it to their students: A study out this week shows that executive brain function — the strongest predictor of academic success — is better in musicians than in non-musicians.

Of course, mounds of previous research has also suggested that playing music makes people smarter, but proving a direct link isn't so easy. Socioeconomic status is a predictor of school grades, but it's also a predictor of being able to afford clarinet lessons. Or maybe people who have the patience and aptitude for music are the same people who have the patience and aptitude for getting good grades — correlation isn't causation.

For example, one study in 2011 tested the intelligence quotient of musician and non-musician children, ages 9-12. They also tested the children for indicators of executive brain function, that is, their proficiency at high-level thinking. Some of these indicators could include their ability to multitask, make good decisions, inhibit bad behavior, and solve problems.

The author, E. Glenn Schellenberg, of the University of Toronto Mississauga, found that music and IQ were correlated, but the relationship between music and executive function was inconclusive. "These results provide no support for the hypothesis that the association between music training and IQ is mediated by executive function," Schellenberg wrote. Yet the neuroscientists behind the current research weren't so sure about that.

The team from Boston Children's Hospital wanted to compensate for the shortcomings of other research. So they removed two important variables: matching the 57 study participants in their control and test groups for equivalent IQ and socioeconomic background (things like the education level of their parents and family income). In the end, they had two groups of children and two groups of adults, similar in many ways — except one group had significant musical training, and the other had very little.

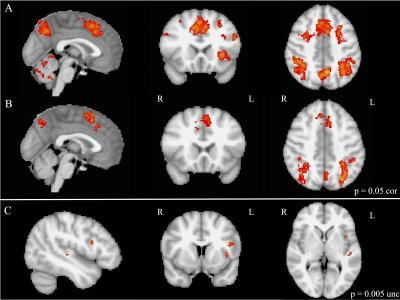

The doctors hooked everyone up to an MRI while administering a series of quizzes — like brain teasers — using things like letters and colors. Meanwhile, they took pictures of their brains in action. The image, above, shows what the scientists discovered. Musicians' brains were more active than the non-musicians' brains, and they performed better on cognitive tests. The results appeared Tuesday in the journal PLoS One.

"Since executive functioning is a strong predictor of academic achievement, even more than IQ, we think our findings have strong educational implications," said lead author Dr. Nadine Gaab in a summary of the findings. "While many schools are cutting music programs and spending more and more time on test preparation, our findings suggest that musical training may actually help to set up children for a better academic future."

This study also furthers the notion that musical training in children with learning disabilities and the elderly could improve their brain function. In a separate 2007 study, 16 adults in a senior home took piano lessons for six months. By the end of it, those 16 had better working memory and multitasking skills than 15 seniors who weren't given piano lessons. "Future studies have to determine whether music may be utilized as therapeutic intervention tools for these children and adults," Gaab said.

But what about causation? This study doesn't actually prove that the musical people weren't predisposed to their talent. In other words, their exceptionally quick thinking and problem solving might be the reason they're so good at music, and not the other way around. The team says its next study will be more like the senior home study, testing people over time to determine which came first, the music or the brains.

Source: J. Zuk, C. Benjamin, A. Kenyon, N. Gaab. Behavioral and Neural Correlates of Executive Functioning in Musicians and Non-Musicians. PLoS One. 2014.

Published by Medicaldaily.com