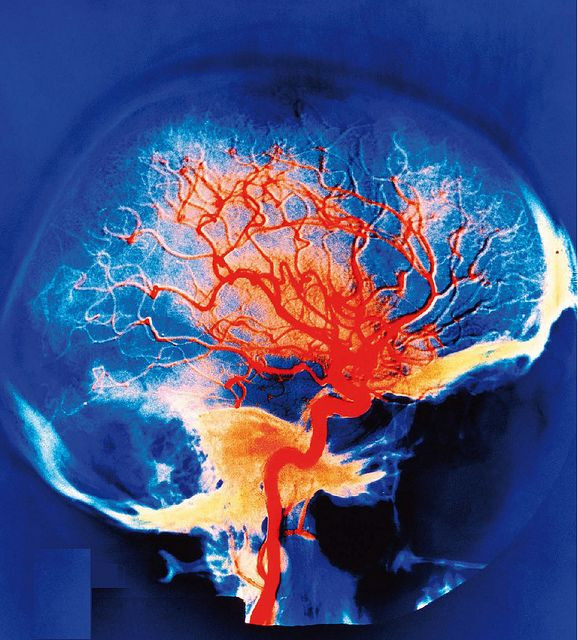

Glioblastoma Diagnosis Usually Comes Late, But New Discovery May Predict This Brain Tumor 5 Years Earlier

People who are diagnosed with a malignant brain tumor known as glioblastoma survive just 14 months on average. Though this brain tumor typically produces symptoms only 90 days before detection, a new Ohio State University study found changes in immune system proteins may occur a full five years before diagnosis, while other alterations begin even earlier.

“We have identified an interaction between [two proteins] and glioma that is present long before tumor diagnosis,” wrote Dr. Judith Schwartzbaum, lead author and associate professor of epidemiology, and her colleagues.

Glioblastomas make up 60 percent of all brain tumors diagnosed in American adults. Though about 10 percent of all patients will survive up to five years following surgery and other treatments, the overwhelming majority will live for just about a year following diagnosis. Why are these tumors so deadly?

One reason is they have the power to suppress the immune system and grow undetected for years. Any cancer caught late is less likely to be cured. However, a team of researchers led by Schwartzbaum suspected this very same power might also spell defeat for the lift-threatening brain tumors.

Allergies & Brain Tumors

The basis for their suspicions could be found in one of their previous studies. Men and women with allergies and asthma have an almost 50 percent lower risk of developing glioma, within 20 years, when compared to people without allergies, Schwartzbaum and her colleagues had discovered back in 2012. Seemingly, there had to be a connection between allergies and brain tumors.

To begin their new study, the researchers gained access to the Janus Serum Bank in Norway. This blood bank contains samples collected over the last 40 years from annual medical evaluations and volunteer blood donors. Because Norway has registered all of its cancer cases since 1953, the research team could cross-reference patients diagnosed with cancer (anonymously identified by number) with the previously collected blood samples.

Next step: Schwartzbaum and her colleagues analyzed protein in the blood samples of 487 people diagnosed with glioma (315 of which were glioblastoma) and 487 people without brain cancer. (Samples spanned about 15 years prior to diagnosis.) Specifically, the researchers examined proteins called cytokines, which are activated by the immune system in response to allergens (the cause of an allergy).

What did they observe? In blood samples taken from 55 patients, the team saw decreased interactions among cytokines five or fewer years before diagnosis of glioma or glioblastoma. In other words, the immune system proteins of patients began to send fewer signals compared to those of healthy people. Mathematicians who have modeled immune function changes in glioma patients believe this weaker signaling means the tumor is starting to suppress (or even beginning to direct) local immune system activation, the study noted.

In the end, the researchers do not know whether allergies reduce cancer risk or if a growing cancer which interferes with the immune response thwarts allergies. Either way, this new information, once supported with additional evidence, “may eventually allow prevention, earlier diagnosis or a better understanding of gliomagenesis,” wrote the authors.

Source: Schwartzbaum J, Seweryn M, Holloman C, et al. Association between Prediagnostic Allergy-Related Serum Cytokines and Glioma. PLOS ONE. 2015.