A History Of Leprosy, The Debilitating Disease Of Separation [PHOTOS]

Throughout history, lepers have been shunned and scorned, ostracized and feared. They were — and in some parts of the world still are — branded with an illness known as the “separating sickness,” which many people feared due to the way it disfigures skin and limbs. Throughout most of history, if you had leprosy, you were doomed to a life of isolation — and could expect to never hold, or even see, your children or family members ever again.

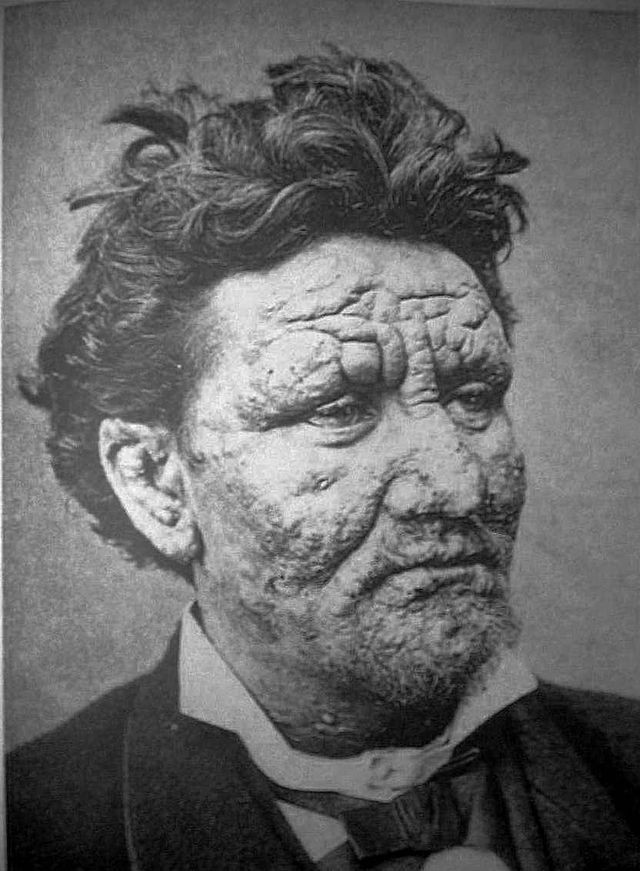

The chronic infection is caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae, or Mycobacterium lepromatosis. The disease starts slow and is very gradual, with symptoms often not occurring for 20 years, and it attacks the granulomas of the nerves, the respiratory tract, and the skin, leading to weakness and deformities. While it’s not very contagious, it’s typically spread through contact with fluid between people.

Ancient

It’s difficult to decipher the first medical recording of leprosy, but some scientists believe it goes as far back as 1550 B.C., when ancient Egyptians wrote about a disease similar to leprosy in a Papyrus document. What researchers are more sure of, however, is that it was written about in the Sushruta-samhita, a medical work from India that was created around 600 B.C.; but it’s likely leprosy existed in India as well as far back as 2000 B.C., according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Thus, there’s general consensus that leprosy likely originated in India or Africa.

But how did it spread throughout Europe and the rest of the world? Some believe that Alexander the Great’s army brought the illness back from India in the 4th century B.C. on their way back to the Mediterranean. Others believe that Pompey’s army brought it from Egypt to Italy in the 1st century B.C. A 2005 study examined origins and distribution of leprosy using comparative genomics, and traced the disease where it originated in Africa and migrated to India, the New World via the slave trade, and Europe.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, there weren’t exactly leprosy colonies per se — rather, shelters existed that were known as leprosy asylums, or leprosaria. Lepers who were wealthy often stayed at home in isolated parts, but poorer lepers were sent to these asylums, where they were mixed in with a larger number of poor, depraved, or ill people. These asylums were run by monks, and were almost always associated with spiritual or religious significance. By the year 1200, there were some 19,000 leprosy colonies throughout Europe.

As if the skin disfiguration and boils of the disease weren’t enough to stigmatize the victims, people in the Middle Ages believed that leprosy was a punishment from God and that patients were literally embroiled in sin. People with the disease were considered dead to society — and their disease was known as the “living death.” Lepers often carried a bell they rang to warn healthy people that a diseased person was coming.

Modern

Between 1200 and 1600, however, the disease in Europe began to decline, though scientists aren’t entirely sure why. In 1873, a Norwegian scientist known as G.H. Armauer Hansen discovered the leprosy bacillus, which led to a societal change in how leprosy was viewed and approached. Leprosy was thus named Hansen’s disease, both after the scientist and also in an attempt to de-stigmatize the illness. Before this time, the only way to “treat” the disease was to separate the victims from the rest of healthy society. Oils for the skin were previously largely used in an attempt to treat boils from the disease, but not much research exists as to whether they were very effective. Targeting the infection itself, however, wasn’t put in place yet.

Throughout the 1800s and 1900s, leper colonies sprouted up in the U.S., particularly in Louisiana and Hawaii. Perhaps one of the most famous leper colonies was Kalaupapa, a tiny settlement on the Hawaiian island of Moloka'i shielded by jaw-dropping cliffs on one side and the wide expanse of the Pacific Ocean on the other. Described as a "prison fortified by nature" by Robert Louis Stevenson, Kalaupapa was home to 1,200 lepers in exile at its peak (back then, laws existed that forced lepers to live in isolation). It was also the home to the famous Father Damien, a Belgian Roman Catholic priest who arrived in 1873 to care for the leper colony and died of leprosy himself.

Currently, there are a few leper colonies that still exist in the world — such as Romania and China — where elderly patients remain after decades of isolation and being removed from their families. They stay because they have nowhere else to go, and they made a life for themselves relying on medical staff and village friends.

Today (Treatment and Cure)

There’s no doubt that laws and attitudes about leprosy have changed in the past century, but stigma still remains in many parts of the world. According to a study released this year, leprosy patients worldwide suffer from discriminatory laws that prevent them from working, traveling, and even marrying, particularly in Thailand, Nepal, and Singapore. The disease continues to affect some 10 million people, and infect 250,000 new cases around the world.

In the U.S., leprosy rates are very low — and they’re typically confined to people who were infected while travelling abroad, or were infected before moving to the U.S. People from the South Pacific who travelled to Hawaii, for example, have the highest rates. According to a 2014 CDC report, approximately 100 new cases of leprosy appear in the U.S. each year, and they’re mostly found in Texas and Louisiana, states that are known for their leprosy rates and still contain some leper colonies. In some cases, people are known to be infected with leprosy by armadillos, who are the only known animals outside of humans to be able to carry the disease.

Today, leprosy is highly treatable and even curable — and getting infected is quite difficult, as the pathogen is notorious for being a weak bug that can’t survive long outside the body. This is why the stigma of fear, discrimination, and isolation that has surrounded the disease for thousands of years must be completely eradicated; doing so will help eradicate the disease itself. In September 2010, the United Nations Human Rights Council passed a resolution to end discrimination against lepers, and while some countries are still lagging behind these guidelines, it’s important that we overcome indifference to remove the outdated perspective on leprosy.