HIV/AIDS Treatments Improve Survival, But The Death Toll Is Still Too High

Incidents of HIV/AIDS have been on the decline in recent years, offering many people hope that the disease may no longer be the death sentence it once was. While this may be true, and new forms of treatment and education are keeping the rates of infection low, recent research suggests that there is still much room for improvement.

A new study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases gathered 30 years of data from more than 20,000 HIV/AIDS patients in San Francisco, concluding that our work is not done yet; in the years between 1997 and 2012, 35 percent or about one-third of AIDS patients still died within five years of being diagnosed with their first opportunistic infection. Researchers feel this is not an acceptable statistic.

“While recent research suggests that many opportunistic infections in the U.S. are now less than common and, oftentimes, less lethal, we cannot forget about them,” said Dr. Kpandja Djawe of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in a press release. “We need to keep them in mind, even in the context of the changing epidemiology of HIV.”

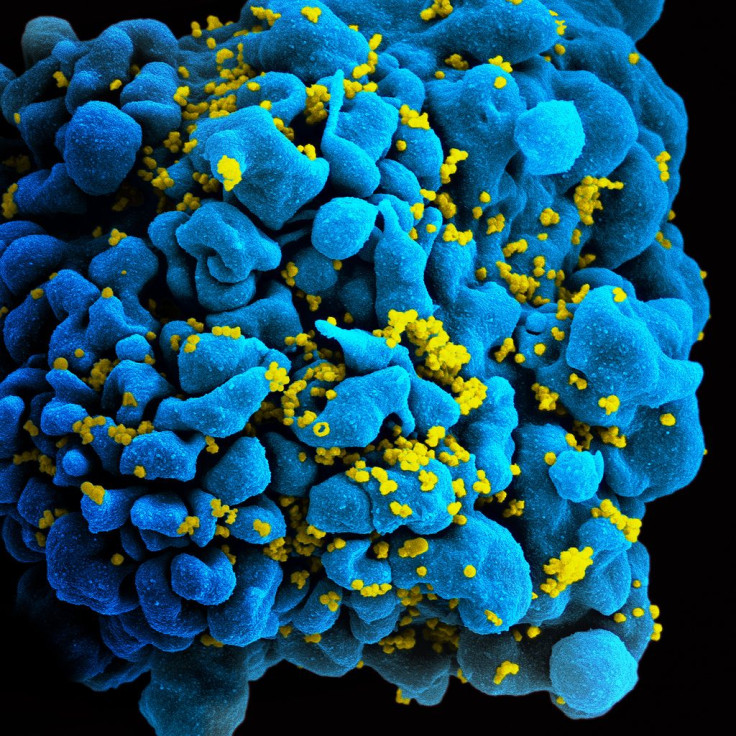

Opportunistic infections, which can often be fought easily by healthy immune systems, pose the greatest risk to HIV patients, especially when the condition has progressed to AIDS. When this progression does occur, the patient’s immune system is too weak to fight off the common bugs we catch every day, leading to severe complications and sometimes death. The study, which gathered HIV surveillance data starting in 1981 from the San Francisco Department of Public Health, found that during the years 1981 to 1986 when the epidemic first rattled the United States, only seven percent of patients in San Francisco diagnosed with their first opportunistic infection survived for more than five years.

The survival rate, luckily, has increased significantly in the years since. Thanks to novel treatments like antiretroviral therapy (ART), which can stop the virus from progressing, increased availability in HIV testing and better treatments for opportunistic infection, 65 percent of patients diagnosed with their first opportunistic infection between the years 1997 to 2012 are surviving past the five-year mark in San Francisco.

This still leaves 35 percent who will not survive — a number researchers believe to still be too high. “Better prevention and treatment strategies, including earlier HIV diagnosis, are needed to lessen the burden of AIDS opportunistic infections, even today, in the combination ART era,” said Dr. Sandra Schwarcz, senior HIV epidemiologist at the San Francisco Department of Public Health.

The CDC notes that across the United States, 13,712 people died due to AIDS complications in 2012 and 50,000 people still get infected each year. This percentage tends to vary among different places in the United States, but is the highest in urban areas, like San Francisco, with more than 500,000 people.

The cause for worry, according to researchers, is that certain opportunistic infections are still exceedingly hard to combat. Diseases like progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), along with infection-related cancers like brain lymphoma still carry a high mortality rate today. Researchers also caution that results in San Francisco are not indicative of the whole country, and areas still remain where HIV/AIDS prevention methods are not as available.

“The results of San Francisco are encouraging, but highlight the need to remain focused on the potential for opportunistic infections to cause devastating disease,” said Dr. Henry Masur and Dr. Sarah Read of the National Institutes of Health. While 35 percent is an improvement from the past, researchers will not be content until that number reaches zero.

Source: Djawe K, Masur H, Read S, et al. Mortality Risk After AIDS-Defining Opportunistic Illness Among HIV-Infected Persons—San Francisco, 1981–2012. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com