How Electrochock Therapy Helps To Treat Patients With Psychiatric Disorders And Depression

It doesn’t sound too pretty: A patient is hooked up to electrodes, which facilitate an electric current entering their brain’s prefrontal cortex. A minute-long seizure ensues. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is often a psychiatrist’s last resort to treat a patient suffering from psychiatric illnesses like major depressive disorder after medications or other forms of psychiatric treatment have failed.

ECT, or electroshock therapy, may conjure nightmarish memories of inhumane treatment in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, but today it’s actually a safe procedure that can effectively treat about 50 percent of the patients for whom it’s used. It’s a procedure that’s completed with the patient’s informed consent, and many times it’s the only thing that can help them.

Yet despite evidence that it works, ECT remains heatedly debated in the psychiatric world. As Irving Reti, director of the Electroconvulsive Therapy Service at The Johns Hopkins Hospital, writes in a report, “[ECT] is hands down the most controversial treatment in modern psychiatry … No other treatment has generated such a fierce and polarized public debate. Critics of ECT say it’s a crude tool of psychiatric coercion; advocates say it is the most effective, lifesaving psychiatric treatment that exists today.”

Here, we’ll try to break down how ECT works, and examine the ways that it harbors risks and benefits to patients with psychiatric illnesses.

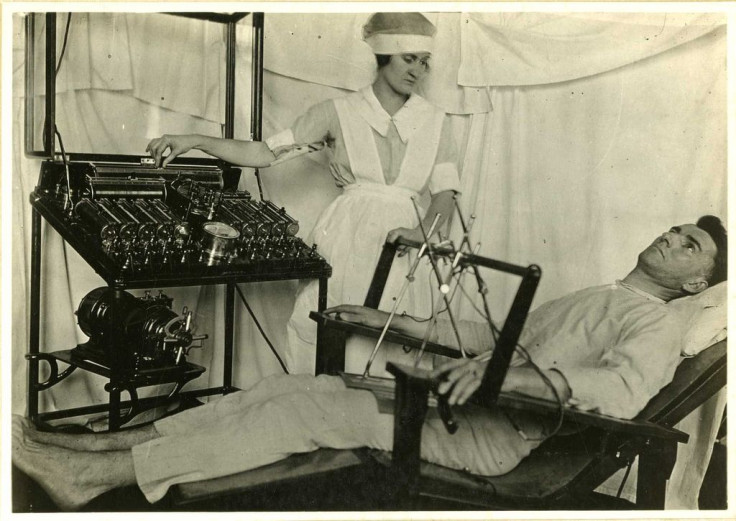

History

The notion that inducing seizures can treat psychiatric disorders has been around for much longer than you think, dating back to the 16th century. But ECT wasn’t used in a medical setting in the U.S. until the 1930s, when researchers injected patients with chemicals to induce seizures. Over time, the chemicals were replaced with electric currents.

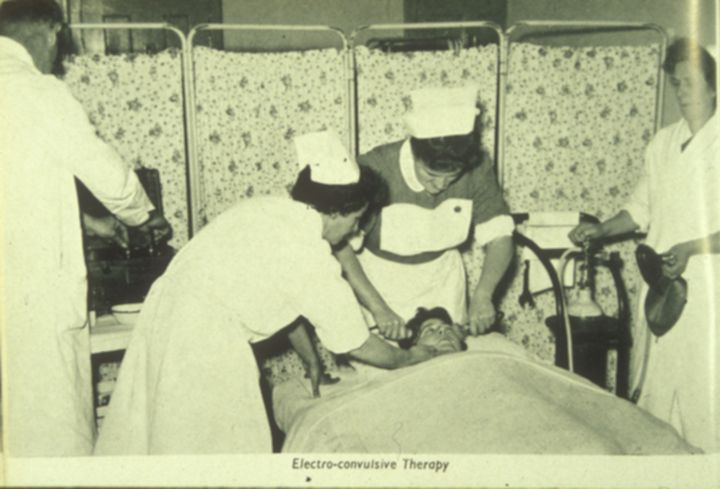

Throughout the 40s and 50s, before the use of antidepressants became widespread, ECT was delivered without any anesthesia or muscle relaxants. According to the Mayo Clinic, it’s ECT’s history — not its present state — that carries most of its stigma. The negative stigma is based on this early process, which involved sending high doses of electricity to the brain without anesthesia, often causing memory loss, fractured bones, and other cognitive problems.

Today, “the therapy is far more refined, with carefully calculated electrical currents administered in a controlled medical setting to achieve maximum benefits with minimal risks,” Reti wrote.

The Process

Before undergoing ECT, a patient must complete a full medical evaluation, including a physical exam, psychiatric assessment, blood tests, an electrocardiogram, and an anesthesia review. Since the patient is on anesthesia during the procedure, they aren’t allowed to eat or drink water after midnight the night before.

ECT itself only takes about five to 10 minutes and can be done as an outpatient procedure. First, a nurse inserts an intravenous (IV) tube into the patient’s arm, which delivers anesthesia, a muscle relaxant, and fluids. The anesthesia renders the patient unconscious, and the muscle relaxant helps reduce the effects of the seizure. Electrode pads are then placed on the patient’s head, depending on which part of the brain is being targeted. The electric currents can focus on one side of the brain (known as unilateral) or on both sides (bilateral), depending on what is being treated.

The doctor then places a blood pressure cuff around the patient’s ankle to prevent the muscle relaxant from reaching the foot. This way, the doctor can monitor the effect of the seizure by keeping an eye on the movement of the foot. During the procedure, the patient is sound asleep and experiences no movement or pain from the seizure. In addition to an oxygen mask, the patient is sometimes given a mouth guard to protect their teeth or tongue.

Finally, the doctor presses a button on the ECT machine, which sends the electric current to the brain, causing a seizure lasting about 60 seconds. While the patient’s brain activity increases significantly, there is no outward indication of it. Once the seizure ends, the medication begins to wear off, and the patient wakes up, typically feeling a bit groggy and confused.

Results And Side Effects

Patients often undergo several ECT treatments over the course of many weeks before seeing any improvement. But by then, their brain chemistry and activity will most likely have been altered. Some side effects include short-term memory loss, confusion, nausea, and headaches — these are all normal and can be handled with medications, or mitigated over time.

Despite the fact that ECT has been used (and improved) for decades, researchers and psychiatrists still aren’t sure how it works. They do know where to place the electrodes on the brain — as research has shown which regions of the brain are associated with depression and other mental illnesses. However, some research hints to why ECT is so effective for treating depression when all else fails.

One 2012 study conducted by researchers in Scotland, for example, examined the brains of nine people with profound depression. The patients showed no response to antidepressants or other therapies, and were therefore given ECT twice a week until their symptoms were alleviated. The researchers used fMRI to scan the patients’ brains before and after the ECT, and found that certain parts of the patients’ brains saw a significant decrease in connectivity, specifically the left side of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. This region has been linked to anxiety, criticism, negativity, and rumination, all of which are factors of depression. The right part of this region, meanwhile, has been associated with optimism and more uplifting ideas.

Researchers believe that ECT somehow rebalances the mix-ups that depression causes. In depressed people, the region associated with rumination and negativity is far more activated than the right side of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. In healthy people, on the other hand, approaching problems is handled with a balance of both the negative and positive areas of the brain.

“It is tempting to speculate that ECT might act to rebalance hemispheric activity [on the right and left side] through modulation of connectivity,” the authors state. In addition, ECT has been found to increase the levels of new brain cells.

Today, the debilitating side effects associated with archaic forms of ECT no longer appear. Patients with major depression, mania, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and catatonia can all be safely treated with the procedure, and in some cases it protects people from suicide attempts. Yes, it may cause short-term memory loss, but when comparing that to the life-threatening, excruciating mental pain caused by psychiatric illness, ECT offers hope to many patients.