How Habits Are Formed, And Why They're So Hard To Change

During the American Psychological Association’s 122nd Annual Convention on Thursday, Wendy Wood, a psychology professor at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, will explain that writing off behavior as a force of habit isn’t a cop out — it's science.

“There is a dual mind at play,” Wood said in a press release ahead of the convention. "Our minds don't always integrate in the best way possible. Even when you know the right answer, you can't make yourself change the habitual behavior.”

Habits are formed after a person has learned something new, like how to parallel park. This process engages the basal ganglia, or the part of the brain located in the prefrontal cortex that works to start and control movement and emotions. From there, it’s a three step process that Charles Duhigg, a reporter for The New York Times and author of The Power of Habit, refers to as a “habit loop.” There’s a cue, or trigger, which signals to your brain to turn a behavior into an automatic routine (parellel parking), followed by the actual routine of the behavior (each time someone finds themself in New York City), and then the reward. The reward, Duhigg told NPR, is the brain’s own personal cue for when it should recall the automatic behavior.

Once that happens, the brain takes a break. "In fact, the brain starts working less and less," Duhigg said. "The brain can almost completely shut down. And this is a real advantage, because it means you have all of this mental activity you can devote to something else." For example, Wood cited one study, which found that participants in the habit of eating popcorn at movies would eat just as much stale popcorn as those who were eating fresh popcorn. "The thoughtful intentional mind is easily derailed and people tend to fall back on habitual behaviors," she said. "Forty percent of the time we're not thinking about what we're doing."

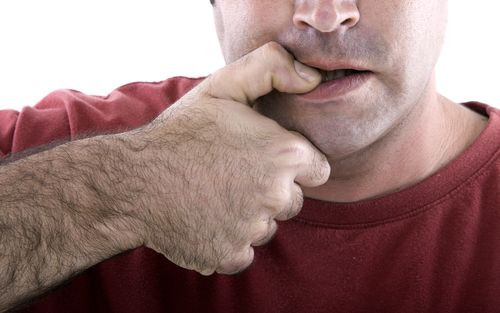

If you're not thinking about what you're doing, how can you possibly change bad habits, like nail-biting, procrastination, and a need for snacks on snacks on snacks? According to Wood, you need to create a window of opportunity to act on new intentions. Think of the fresh start that comes with moving to a new city. Changing your environment, whether it’s across country or in the kitchen, can disrupt old behaviors, making it easier to create new ones.

What not to do: set a deadline. Some researchers suggest it takes 15 days to create a new habit, others suggest over 250 days. Do, however, give your brain context clues. Repeating a behavior in the same context is what makes it easier for your brain to coast on pilot mode.

"What we know from lab studies is that it's never too late to break a habit," Duhigg said. "Habits are malleable throughout your entire life. But we also know that the best way to change a habit is to understand its structure — that once you tell people about the cue and the reward and you force them to recognize what those factors are in a behavior, it becomes much, much easier to change."

Source: Wood W. Habits in Everyday Life: How to Form Good Habits and Change Bad Ones. At The American Psychological Association's 122nd Annual Convention. 2014.

Published by Medicaldaily.com