A Brief History Of The Menstrual Period: How Women Dealt With Their Cycles Throughout The Ages

If stigma around menstruation exists today, you can rest assured it was much worse in earlier times throughout history. Without much knowledge about biology or the human reproductive system, ancient and medieval humans simply saw menstruation as females bleeding without being injured — a phenomenon that appeared to correspond to changes in the moon. For thousands of years, menstruating women were wrapped up in labels and misinformed religious beliefs — at times considered holy and mystical, at other times seen cursed and untouchable.

Often, menstruation was completely omitted from man’s documented history, relegated to the “woman’s sphere.” So here’s a brief history of menstruation in both scientific and cultural life, considering the fact that there still remains far more to discover about the subject.

ANCIENT

Though females have experienced menstruation since before humans even fully evolved as a species, there’s very little documentation about periods among ancient peoples. This is likely due to the fact that most scribes were men, and history was mainly recorded by men. As a result, “we don’t know whether women’s attitude [about menstruation] was the same [as men’s] or not,” Helen King, Professor of Classical Studies at the Open University, writes. “We don’t even know what level of blood loss they expected… but the Hippocratic gynecological treatises assume a ‘wombful’ of blood every month, with any less of a flow opening up the risk of being seen as ‘ill.’”

It’s very likely that women in ancient times had fewer periods than they do now, due to the possibility of malnourishment, or even the fact that menopause began sooner in earlier eras — as early as age 40, as Aristotle noted. However, there’s little evidence surrounding how ancient women handled blood flow.

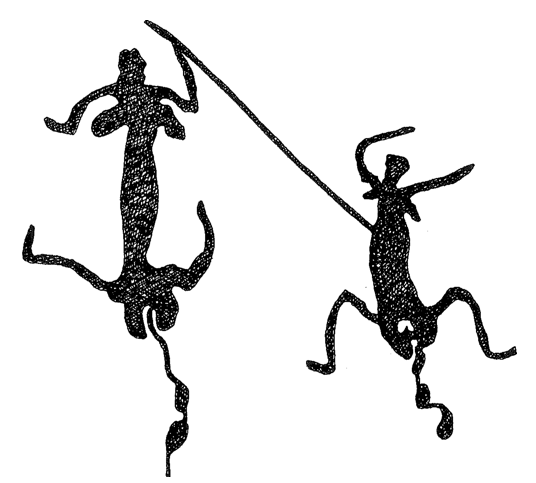

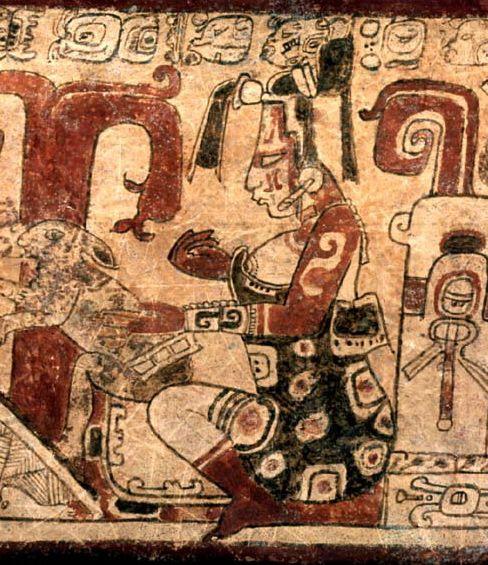

Historians do know that in many parts of the ancient world, menstruating women were strongly associated with mystery, magic, and even sorcery. For example, Pliny the Elder, a Roman author and natural philosopher, wrote that a nude menstruating woman could prevent hailstorms and lightning, and even scare away insects from farm crops. In Mayan mythology, menstruation was believed to have originated as a punishment after the Moon Goddess — who represented women, sexuality, and fertility — disobeyed the rules of alliance when she slept with the Sun god. Her menstrual blood was believed to have been stored in thirteen jars, where it was magically transformed into snakes, insects, poison, and even diseases. Interestingly, in some cases, the ancient Mayans believed the blood could turn into medicinal plants too.

Period blood held plenty of different meanings in ancient cultures, and was often used as a “charm” of sorts based on a belief that it had powerful abilities to purify, protect, or cast spells. In ancient Egypt, the Ebers Papyrus (1550 BC) hinted at vaginal bleeding as an ingredient in certain medicines. In biblical times, ancient Hebrews upheld laws of Niddah, in which menstruating women went into seclusion and had to be separated from the rest of society for seven “clean” days.

Despite these mythological or even medicinal hints at menstruation, however, it’s generally unknown what women used as ancient tampons or pads. Assumptions of ragged cloths that were re-washed, tampons made of papyrus or wooden sticks wrapped in lint, or “loincloths” in Egypt have circulated, but no one really knows what women in fact used during this time.

MEDIEVAL

Once again, hundreds of years passed without much documentation about menstruation in the Middle Ages, so historians don’t have much to work with other than speculation. The scholar who has probably written the most about the subject is Dr. Sara Read. Read explored how European women in the Middle Ages and early modern area dealt with menstruation, and generally concludes that aside from using rags or other absorbent materials on occasion (hence the term “on the rag”), many medieval European women simply bled into their clothes.

Not surprisingly, there was plenty of religious shame associated with menstruation, particularly in medieval Christianity. “With a certain amount of shame attached to menstruation as a process, and genuine horror affixed to the blood itself, it’s no surprise that women took pains to mask their cycles from public view,” Greg Jenner, a British public historian, writes on his blog. “In medieval Europe they carried nosegays of sweet-smelling herbs around their necks and waists, hoping it would neutralize the odor of blood, and they might try to stem a heavy flow with such medicines as powdered toad. However, pain relief was not readily permitted by the Church: God apparently wanted each cramp to be a reminder of Eve’s Original Sin.”

MODERN

1879. Sometime in the late 19th Century, concern grew around the notion of whether bleeding into one’s clothes was healthy and sanitary. One German doctor wrote in the book Health in the House: “It is completely disgusting to bleed into your chemise, and wearing that same chemise for four to eight days can cause infections.” Around this time, a report in the British Medical Journal described a new tampon-like device to be inserted into the vagina, though it’s not clear if it was meant to be used for periods.

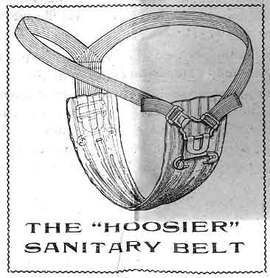

Enter the Hoosier sanitary belt, an odd contraption worn under women’s garments. From the late 1800s until the 1920s, women could purchase washable pads that were attached to a belt around the waist.

1888. The first commercially available disposable menstrual pads appear, known as Lister’s Towels and developed by Johnson & Johnson. Around the same time, nurses began using wood pulp bandages they found in the hospital as disposable pads. Because it was a highly absorbent material normally used to bandage wounds, and was cheap and disposable, it worked well to soak up menstrual blood flow. This same material was later used for the first Kotex pads.

1929. But the first tampon wasn’t invented until 1929, developed by Dr. Earle Haas. Haas originally got the idea for the tampon after learning his friend in California used a sponge tucked into the vagina to absorb blood. He had the idea to take strips of cotton fibers connected to a cord that extended out of the vagina for the person to pull out. Around this time, in order to purchase commercial "feminine" products, women had to clandestinely place money into a box at the store instead of buying in front of the salesperson, as shown below.

1980s. The belted sanitary napkin, like the Hoosier belt, was almost entirely faded out by the 1980s. Pads by now had adhesive strips on the bottom that could be attached to underwear, and in the next few decades the ergonomics were tweaked in order to make pads more absorbent and avoid leaking.

Of course, biological knowledge about menstruation has largely improved since the early 20th century, and most women in developed countries have access to clean and safe period products. We’ve even come so far as to develop a new type of underwear specifically designed for periods, known as Thinx. But in many parts of the world, menstruation is still stigmatized and considered taboo — and thousands of women don’t have access to sanitary products. In India, for example, women in certain rural areas are still viewed as "untouchables" who are dirty and unpure during their periods. It goes without saying that the vast majority of these women must use homemade sanitary cloths or none at all, which of course over time gets to be quite unhygienic. It will take some time before menstrual hygiene and education can be brought to all corners of the globe, providing women with safe and non-shameful ways to deal with their periods.