New Dietary Guidelines Bring Back Saturated Fat, Cholesterol; Why Experts Don't Owe An Apology For Backtracking

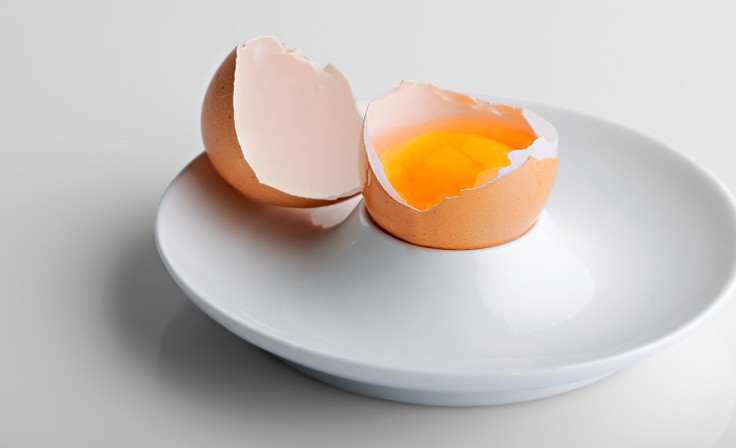

“Ask, and ye shall receive,” right? Following an increasingly fierce fight against added sugars and cholesterol (the latter fight being whole eggs, plural), the U.S. Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS) have proposed new federal dietary guidelines. The gist of the 571-page-long report is egg yolks are back from exile; drinking coffee doesn’t up risk for disease; moderate alcohol consumption is OK, too; and so are low amounts of saturated fat.

The key word here is proposed: The Atlantic reported that the recommendations aren’t finalized until the end of the year, and that’s after a two-month comment period open to the public at Health.gov. But for the most part, the committee’s findings are consistent with what’s already in place. This is to say a diet high in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, as well as moderate to low amounts of dairy, alcohol, meats, sweets, and refined grains, is the way to eat for optimal health.

Some of you may be thrilled, if only because now you can stop pretending to like egg whites; no disrespect to Ben Affleck. On the other hand, some of you may want an apology from the nutritionists, experts, and institutions who have long warned you against fatty cholesterol and heart disease-causing saturated fat. If you fall into the latter category, I’m sorry, but no.

Redemption Song

Cholesterol has been on a sort-of blacklist since 1961, after the American Heart Association (AHA) published what became a defining study that found too much cholesterol in the blood — courtesy of foods like butter, eggs, and cheese — increased risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) and heart attack. Yet, in later years, it emerged that cholesterol could be essential in the right amount. For example, one study from the University of Connecticut found dietary cholesterol through egg yolks can actually boost a person’s HDL, or good cholesterol. In this case, only those with preexisting conditions, like diabetes, should err on the side of caution.

Longstanding warnings against saturated fat have also started to unravel.

“When you consume a very low-carb diet, your body preferentially burns saturated fat,” said Jeff Volek, a professor of human science at The Ohio State University, in a press release for a study he conducted. “We had people eat two times more saturated fat than they had been eating before entering the study, yet when we measured saturated fat in their blood, it went down in the majority of people. Other traditional risk markers improved, as well.”

It’s worth noting Volek’s study was done on a small scale, involving only 16 overweight or obese men and women between the ages of 30 and 66, with one participant dropping out of the study after developing high blood pressure. And while a larger meta-analysis on saturated fat published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition echoed Volek’s findings, researchers conceded “the available data were not adequate for determining whether there are CHD or stroke associations with saturated fat in specific age and sex subgroups.” But already, resources such as the AHA have acknowledged that full-on avoiding saturated fat is misguided; they now propose it can be part of a healthy diet.

This is science, Dr. Corey Hilmas, senior vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs at the Natural Products Association, told Medical Daily. It takes time for science to evolve and, as my co-worker previously explored, “more often than not, finding links is the best science can do.” That’s not to say initial guidelines got it completely wrong, though this answer will vary depending on who you’re asking. It means we’re getting to a point where science and research are more refined and efficient — this is weird to apologize for.

What’s Right To Eat

I understand the search for an apology stems from the way basic principles of healthy eating are pushed. In a word, aggresively. No eggs. No meat. No this or that. Given every one of us is different, meaning different bodies, health conditions, and general taste, it’s frustrating and confusing to be told — worse yet, shamed for — what you can and can’t eat.

Yet, it gets tricky when you focus on new links and developments singularly. Take saturated fat, for example. The fact that its link to heart disease has come into question shouldn’t give anyone license to go, ahem, ham. Animal protein is a rich source of this type of fat, and red and processed meat is problematic in its own right. Studies have shown increased meat consumption may increase risk for heart disease, breast cancer, and type 2 diabetes. However, if you enjoy a lean cut of organic, grass-fed hamburger, paired with vegetable-heavy sides and whole grains, the nutrional quality of the dish suddenly improves. Saturated fat, cholesterol, and other nutrients of concern will impact us differently depending on how they're sourced and served. A balanced diet is essential, Hilmas said.

Guidelines are just that, guidelines. Healthy eating requires an individualized approach. It also requires some common sense. A diet promising to help you lose weight in five days is hyperbole; Hilmas said losing a half-pound to a pound per week is the healthier approach to weight loss and improved health. In fact, this is where current guidelines come up short for him. There are so many hyperbolic, nutrient-exclusive diets out there (many of which were recently ranked) that the committee didn’t evaluate; Hilmas would have liked added clarity there.

Nutritional information and data is ever-evolving. When the committee reconvenes five years from now (as they do every five years), the guidelines may redeem another nutrient of concern. Or perhaps they’ll condemn ambivalent products, like diet soda. The Atlantic reported the proposal found “aspartame is probably okay in moderation, though artificial sweeteners should not be promoted in approaches to weight loss.” That diet soda wasn’t exclusively explored in the report was another concern for Hilmas; “the latest research says it can lead to a 36 percent increase in the chance of metabolic syndrome and diabetes.”

Until then, until this end-all be-all research is conducted, science, the AHA, and other resources are acknowledging and incorporating new ideas and evidence into their own guidelines and recommendations. Reluctance to adhere to this notion is a personal problem.