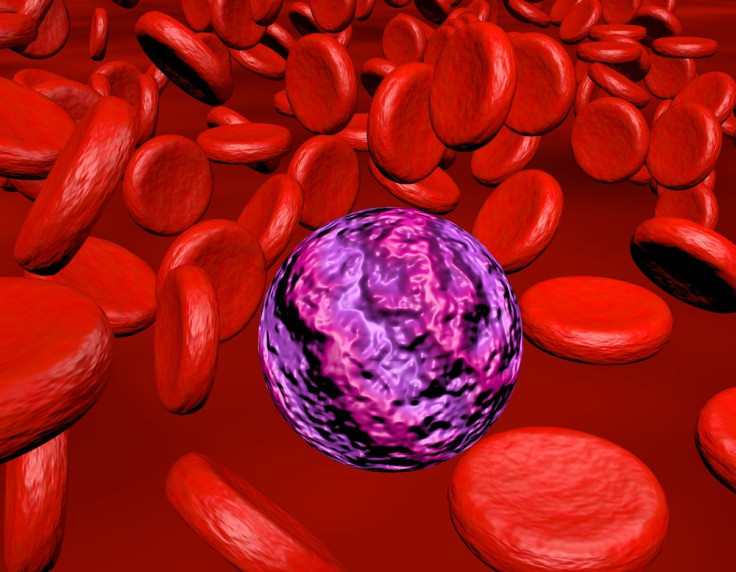

Non-Toxic Leukemia Treatment Kills Cancerous Cells While Avoiding Normal Cells

Chemotherapy is considered the most popular form of cancer treatment; however, patients tend to experience powerful side effects due to the death of normal cells that surround cancer cells. Scientists from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute conducting research at the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine and the Harvard University Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology have discovered a treatment that targets leukemia metabolism and destroys cancerous cells while avoiding other types of cells.

"It's been known for decades that cancer cells use energy differently than most cell types," senior author Dr. David Scadden said in a statement. "So we thought, maybe there are metabolism differences between blood stem cells and their immediate descendants; and are they so different from cancer that you might be able to manipulate energy sources with something that could have an effect on cancer and not harm normal cells?"

Scadden and his colleagues analyzed the nutrients of blood stem cells and blood progenitor cells, which are a direct offspring of blood stem cells with limited ability to differentiate. Two methods for manipulating the nutrients in cells were studied: one that acted as an on-off switch for glucose and a second that acted as a volume dial by raising or lowering glucose. While switching glucose off caused stem cells to die, raising glucose levels resulted in favorable energy production in progenitor cells.

In the next step of the study, corrupted genes were introduced to the parental blood stem cells and progenitors, which turned them cancerous. After exposing cancerous cells to the on-off switch mechanism and the volume dial mechanism, researchers determined that leukemia cells were sensitive to both forms of manipulation. These results show that targeting the metabolism of leukemia could be an effective way to kill only cancer cells and avoid normal cells.

"That was an interesting distinction between these two cell types," Scadden said. "They have very different functions, and you might imagine they're going to use their nutrients very differently, but nobody had defined that before. Cancer cells are not like normal cells in a lot of ways, but one of them is that they get locked into a particular way of behaving. These cells are so singular in the way they handle glucose that they create a unique opportunity to intervene. Normal cells don't get so disrupted because they have other energy mechanisms in place."

According to the American Cancer Society, side effects experienced by people who take chemotherapy drugs or endure radiation therapy, include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, anemia (having a lower red blood cell count than normal), sexual side effects, infertility, and a condition that causes a buildup of lymph fluid in the fatty tissues under the skin, known as lymphedema. Private drug manufacturers are currently looking into medication options that target cancer metabolism in solid tumors.

"One of the major hurdles for cancer therapy is that while the drugs are effective in killing cancer cells, they are toxic to normal cells," said study first author Dr. Ying-Hua Wang, a postdoctoral fellow in the Scadden Lab. "In this study, we found a way to differentiate sensitivity between normal and malignant cells, suggesting a potential therapeutic angle."

Source: Dongjun W, Wang Y, Scadden D, et al. Cell state-specific metabolic dependency in hematopoiesis and leukemogenesis. Cell. 2014.