Opinion: Nutrition Facts Labels May Soon Include Added Sugar Info; Food Companies Protest Despite Risks Of Obese, Diseased America

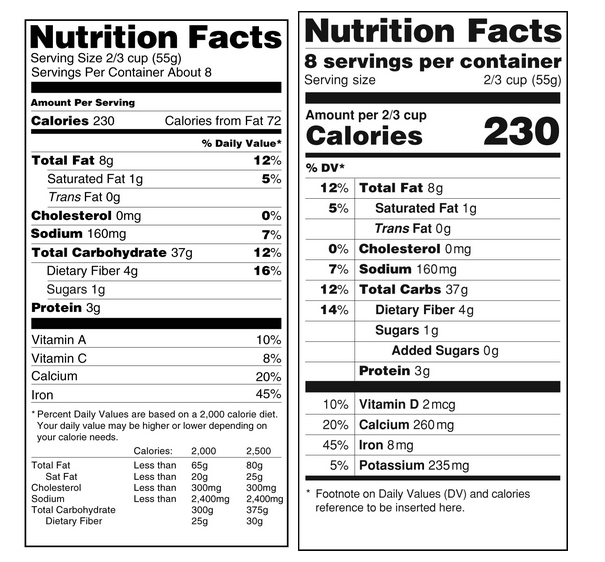

Calories, sugars, fats, and carbohydrates have all been blamed for America's obesity epidemic. But as it turns out, the problem may have just been a matter of miscommunication this whole time, as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is in the process of a nutrition fact labeling overhaul. When the average American looks on the back of a cereal or juice box, they have no concept of what a gram looks like. Four grams of sugar equals 1 teaspoon, but you shouldn't have to be a dietician or mathematician to figure out how much you're eating.

Why Is There Convoluted Information Hidden On The Back Of The Package?

Added sugar is the sugar that’s literally added to a product after it’s made, while naturally occurring sugar is found in fruits, along with healthy fiber, yet both are calculated together and put on nutrition labels. Out of 600,000 food items in a grocery store, 80 percent contain added sugar, and it's hidden in foods we'd never think to double check. Take a can of Campbell's tomato soup for instance. One cup of soup contains 3.5 teaspoons of sugar; of course, that's the translated version and not what the label actually says. Instead, the soup's label says it has 14 grams of sugar in half a cup — one serving size. But with many people unable to determine what 14 grams of sugar is, it's likely they're not aware of, or paying attention to, serving sizes, either.

It's no wonder why Campbell's Soup Company has written letters to the FDA requesting it be exempt from the added sugar ruling. It's not alone. The FDA has been overcome by requests from every food company, from the National Yogurt Association to the National Frozen Pizza Institute. The people at Ocean Spray Cranberries, Inc. wrote a letter to the agency saying, “Cranberries ... are naturally low in sugar, giving them a distinctively tart, astringent, and even unpalatable taste,” which is why their products need so much added sugar — consumers just won't understand. The American Beverage Association agreed, stating that a transparent added sugar label “may carry an unfair negative connotation that undermines the factual nature of nutrition information.”

Nutrition labels were introduced 20 years ago, with the intention of providing consumers with an easy-to-use breakdown of what they were eating. The FDA has looked at the labels currently in place, reflected upon the new needs of the American public, and as a result, made some important proposal changes. Foods that are intended to be eaten in one sitting, such as an ice cream bar or small bag of chips, should be labeled as one serving, with calories, sugars, fats, carbohydrates, etc. calculated and listed specifically for the product. The agency has also proposed emboldening and enlarging calorie and serving size listings, which makes sense. But among all of the proposals, the one for added sugar has worried food companies the greatest.

When the FDA welcomed comments regarding the proposals this past summer, demands from expert groups, citizen petitions, federal agencies, and the general public came flooding in about added sugar labels. According to the FDA, added sugars provide no nutritional value and are often referred to as empty calories. The average American consumes 22 teaspoons of added sugar a day, totaling 350 extra calories, according to the Harvard School of Public Health. Meanwhile, the American Heart Association is also concerned, because of sugar's contribution to cardiovascular diseases. It recommends we consume no more than 6 teaspoons a day.

What Is Sugar, Really?

Sugar is made of two different molecules — fructose and glucose. When digestion breaks it down, glucose separates and circulates in our body, feeding our muscles and brain. But fructose targets the liver, and when eaten in excess, the body has no other choice but to convert the sugar into liver fat. Thus it causes obesity, and continued consumption fuels development of some of the most dangerous chronic diseases, including heart disease, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers. If "fructose" sounds familiar, there's a good chance you've heard of high fructose corn syrup, which is almost chemically identical to added sugar, along with 255 other sugar look-alikes with alias names listed on ingredients labels.

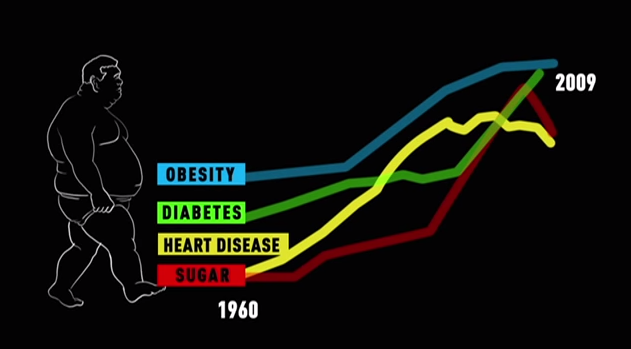

As consumption of sugar grows, so do Americans' bodies. Is it really a coincidence that rates of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and the use of sugar have increased at a nearly identical pace? In the 80s and 90s, experts blamed dietary fats for causing high rates of cardiovascular disease. But after we eliminated them from our diets, and still saw that our health was at risk, doctors and nutritionists finally realized there was another, more dangerous culprit to blame: sugar.

A Half-Baked Attempt At Social Responsibility

Let's rewind 15 years, to a historic meeting in Minneapolis, during a time when obesity was only an emerging problem, a blip on a few people's radars. The heads of America's biggest food corporations, including Kraft, Coca-Cola, General Mills, Nabisco, and Nestle, met in Pillsbury's headquarters to discuss obesity. It was a rare convergence of enemies, each fighting the other for eye-level spots on grocery store shelves and primetime commercial slots. The meeting was intended to discuss a growing fear, the obesity epidemic.

Their fears were rational. After all, they had just seen the tobacco industry settle a costly lawsuit that found it liable for causing death and disease among consumers. The food execs looked at slide shows of obesity rates spreading across the U.S. like a mysterious plague, and they were concerned they would be held responsible for the growing epidemic. When they left the meeting, they had decided that they'd fulfill their social responsibility quota by offering consumers low-fat or low-sugar options. But numbers don't lie, and they saw that the healthier options weren't enough to sway consumers past the temptation of what they really liked. These products go beyond tasting better; marketing psychologists design the products with certain colors and phrases to subconsciously catch our eyes, and drive our hands deeper into our size 16 jean pockets in search of some cash.

More than one-third of U.S. adults are obese, and following close behind are American children, which is surely a greater concern. In the last 30 years, childhood obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. These children are the future of our country, yet we allow food companies to prep their young taste buds with sugar-laden cereals, fried chicken products, and trans fat-filled snacks. But it makes sense that they'd target our children, the future consumers of their products. After all, if the goal is to make money, then a playpen is a goldmine. Securing snacktime, then, becomes a guaranteed way to surpass the competition.

If I owned a juice company and had no moral obligations, there's no way I'd want parents to find out how much sugar was being poured into their kid's drinks. I'd fight the FDA for special treatment so that my drink's contents can hide behind a confusing nutrition label. Hopefully, the FDA can look past the money being offered by food-giant lobbyists, or else we may all find ourselves at risk of disease, and growing old with a lower quality of life.