Opioid Use For Chronic Pain Greater Among Vets, Whether They Need It Or Not

Military veterans returning from deployment face bouts of chronic pain and consume prescription opioid painkillers at rates far higher than the civilian population, a new study finds, although that pain may still be undertreated on a wider scale.

The agonies of war aren’t confined to the battlefields. Soldiers return home, to the loving embrace of their families, but often face hardship when it comes to reintegrating into civilian life. Part of this struggle is overcoming physical wounds sustained during deployment, from shrapnel injuries to overstressed nervous systems. Now a growing body of research is interested in learning what happens to these overworked brains and bodies, particularly as the nation’s health care system wanes in veteran compassion.

"War is really hard on the body," study author Lt. Cmdr. Robin Toblin, a clinical research psychologist at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., told Health Day. "People come home with a lot of injuries, and as you can imagine they experience a lot of pain. There seems to be a large unmet need of management, treatment, and assessment of chronic pain."

Toblin and his co-researchers collected data on nearly 2,600 soldiers in the same infantry brigade. These soldiers filled out anonymous questionnaires related to feelings of chronic pain and experiences with prescription painkillers. Roughly 44 percent of the soldiers reported chronic pain even three months after returning home, which was just about double the civilian rate of 26 percent.

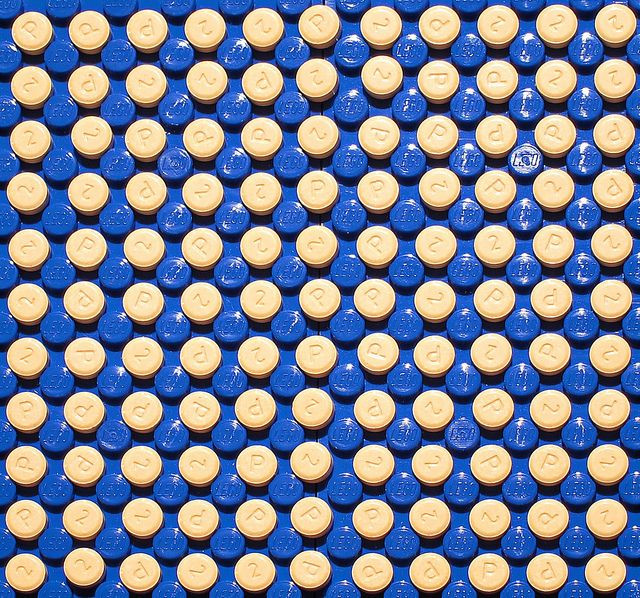

Perhaps more alarming were the 15 percent of vets who took painkillers to treat their pain, compared to the four percent of the rest of the population. And in the same way many doctors write prescriptions for their patients as a kneejerk reaction to pain, as opposed to non-pharmacological options, experts believe there’s even greater cause for concern when those patients are soldiers. Dr. Wayne Jonas, a retired Army lieutenant colonel and president of a non-profit health organization, commented in a related editorial that injury and a sense of weakness too often go hand in hand.

“The nation’s defense rests on the comprehensive fitness of its service members,” he wrote, which needs to be joined in “mind, body, and spirit.” And treating chronic pain with medication may be a dangerous path to travel. Prior research has shown that pain meds do their best work for acute pain — mild headaches, sore joints — and long-term alternative therapies offer the greatest relief for chronic pain. As Jonas points out, these include yoga, t’ai chi, and music therapy, but also more advanced techniques such as electrical stimulation and implants.

Some other startling facts arose from the study. Among those with chronic pain, 48 percent said their pain had lasted a year or longer, and 55 percent said they suffered daily or constant pain. But what alarmed Toblin and Jonas the most were the 44 percent of soldiers using painkillers who hadn’t experienced pain within the last month. This, they argued, could signal addiction.

"When you need pain relief, you can throw something at it,” Toblin said, “but it's not necessarily good for you to use them all the time." More important is teaching soldiers how to self-manage their pain, instead of craving the escape to pills. Among a population whose brains are already splintered from the horrors of war, introducing another substance that messes with brain chemistry may only spell disaster.

Source: Toblin R, Quartana P, Rivierie L, Walper K, Hoge C. Chronic Pain and Opioid Use in US Soldiers After Combat Deployment. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014.