Preventing Bipolar Disorder In High Risk People May Begin With Neuroplasticity, A Natural Rewiring Of The Brain

A family history of illness increases a person’s risk of developing bipolar disorder, yet many people at high genetic risk never develop this mental illness. Researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai have discovered a possible reason why: Some high risk people show naturally occurring rewired connections in their brains that compensate for inherited abnormalities.

"Our findings suggest that resilience to genetic risk of bipolar disorder may reflect the capacity to adapt network connectivity to ameliorate the effects of underlying network dysfunction," wrote the researchers.

Someday, this new research suggests, neuroplasticity may become the basis for new and innovative treatments to help those who suffer from this often debilitating illness.

Bipolar disorder, also known as manic-depressive illness, causes fluctuations in mood, energy, and activity levels, explain the researchers. In severe cases, patients may lose their ability to carry out day-to-day tasks. Heritability is high, ranging between 60 percent and 85 percent, yet the underlying genetics of this mental illness are complex. While patients with bipolar disorder and their unaffected relatives may have similar genes, brain abnormalities that can be seen on a scan (neuroimaging) may or may not be shared.

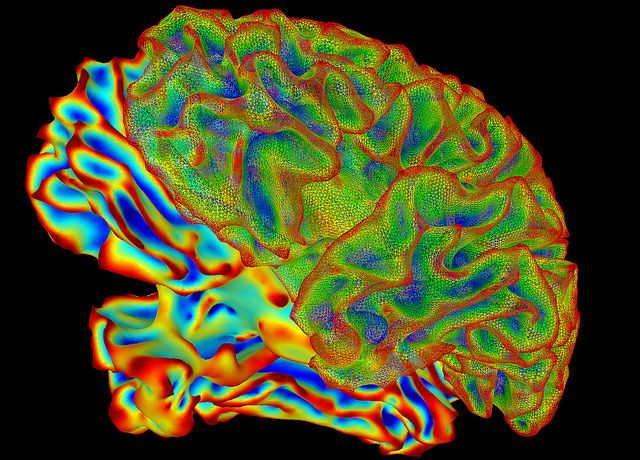

When a neuroimaging abnormality is present between two siblings, this is considered a genetically-driven marker of risk. When an abnormality is present in a patient but not in the relative, this is considered a marker of disease expression. To figure out which abnormalities indicate risk and which indicate disease, the Mount Sinai research team conducted an experiment using fMRI brain scanning technology.

For comparison purposes, they mapped the connectivity patterns of three distinct groups: bipolar disorder patients; siblings of patients who did not develop the illness; and unrelated healthy people. While having their brains scanned, each participant was asked to perform two separate tasks, one emotional and one non-emotional. Each task tapped into a different aspect of brain function affected by bipolar disorder.

Emotional processing is where the researchers saw a difference. The patients and their resilient siblings showed similar abnormalities in the wiring of their emotional brain networks. However, within these networks, the siblings displayed additional modulations in the wiring of their brains — a rewiring had occurred to compensate for the inherited abnormality.

The researchers say resilient siblings have a natural mechanism, a form of adaptive neuroplasticity, that helps them overcome the disease. These siblings remain well “even though they still carry the genetic scar of bipolar disorder when they process emotional information,” Dr. Sophia Frangou, lead author and a professor of psychiatry, said in a press statement.

Source: Dima D, Roberts RE, Frangou S. Connectomic markers of disease expression, genetic risk and resilience in bipolar disorder. Translational Psychiatry. 2016.

Published by Medicaldaily.com