Skin-Like Device Uses 3,600 Crystals To Monitor Heart Health, Moisture Levels

A tiny new patch could deliver important information regarding users’ heart health and skin moisture levels, based on successful early efforts by researchers from Northwestern University and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

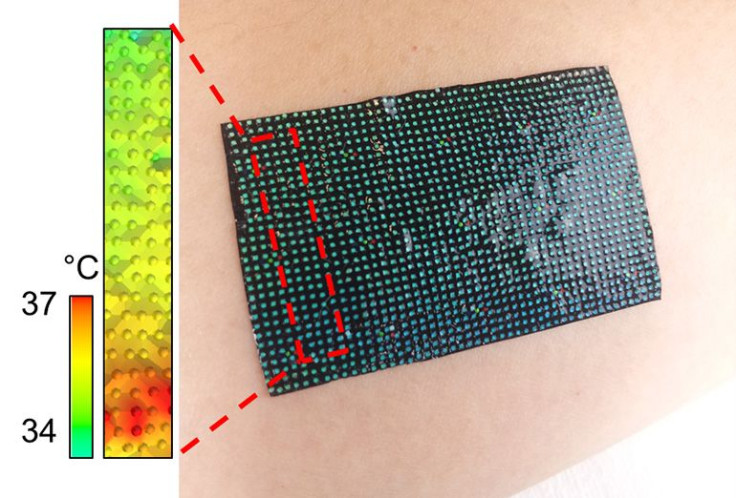

A new study shows the patch is flexible, durable, and able to be worn around-the-clock — qualities, the researchers argue, which make it ideal for wireless health monitoring. Changes in the device’s color signal a temporary loss or increase of blood flow, which may be of clinical significance in matters of skin hydration and cardiovascular health.

Right now, the patch is still in the lab-testing phase. More research needs to be done to hone the particulars, such as how the user can easily obtain the relevant data. In the meantime, the researchers sing the device’s praises for its victories in proving the principle.

“These results provide the first examples of ‘epidermal’ photonic sensors,” said John A. Rogers, the paper’s corresponding author and professor of materials science and engineering at the University of Illinois, in a statement. “This technology significantly expands the range of functionality in skin-mounted devices beyond that possible with electronics alone.”

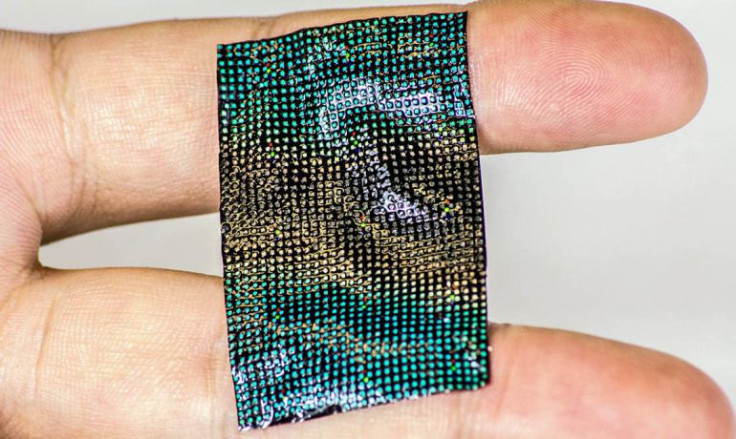

The magic of the device is in the 3,600 liquid crystals that live on its surface. Each one half a millimeter square, the crystals provide individual temperature points that react with the presence or absence of heat under the skin. Hospitals currently make use of expensive infrared technology to accomplish the same task. The new device is both portable and low-cost, the team asserts.

“Our device is mechanically invisible — it is ultrathin and comfortable — much like skin itself,” said Northwestern’s Yonggang Huang, one of the senior researchers. Huang and the team tested the device on people’s wrists. Along with its clinical significance, Huang points out, the patch could also have aesthetic advantages.

“One can imagine cosmetics companies being interested in the ability to measure skin’s dryness in a portable and non-intrusive way,” Huang said. “This is the first device of its kind.”

Skin temperature has been well-studied and confirmed as a predictor of blood flow quality. As the brain’s hypothalamus detects changes in external temperature — like extreme heat, for example — it emits nerve impulses that tell blood vessels to open, letting more heat reach the skin, which can then escape as heat loss.

When the heart fails to supply this blood in sufficient quantities or at consistent rates, the new sensor will change color. It detects these changes through a wireless heating system powered by electromagnetic waves present in the air. Further tests will confirm the patch’s effectiveness and improve upon its ability to avoid error. As for the convenience factor, the research team is confident that part is already secured.

“The device is very practical,” said Yihui Zhang, co-author and research assistant professor. “When your skin is stretched, compressed, or twisted, the device stretches, compresses or twists right along with it.”

Source: Gao L, Zhang Y, Malyarhcuk V, et al. Epidermal photonic devices for quantitative imaging of temperature and thermal transport characteristics of the skin. Nature Communications. 2014.