Skipping Meals Promotes Belly Fat Storage, Increases Risk For Insulin Resistance

Anyone looking to lose weight knows they have to restrict the amount of calories they consume, but how much and when they restrict those calories can make all the difference. A recent study conducted at Ohio State University has revealed that skipping meals not only leads to abdominal weight gain, but it can also lead to the development of insulin resistance in the liver.

"This does support the notion that small meals throughout the day can be helpful for weight loss, though that may not be practical for many people," Martha Belury, professor of human nutrition at Ohio State University, said in a statement. "But you definitely don't want to skip meals to save calories because it sets your body up for larger fluctuations in insulin and glucose and could be setting you up for more fat gain instead of fat loss."

Belury and her colleagues divided mice into two groups: one group that was put on a restricted diet and a second group that was put on an unlimited diet. Mice from the restricted diet group received half of the calories that were given to the unlimited diet group in the first three days before having additional calories added. Although mice in the restricted diet group initially lost more weight compared to those from the unlimited diet group, they regained that weight as calories were added back into their diet.

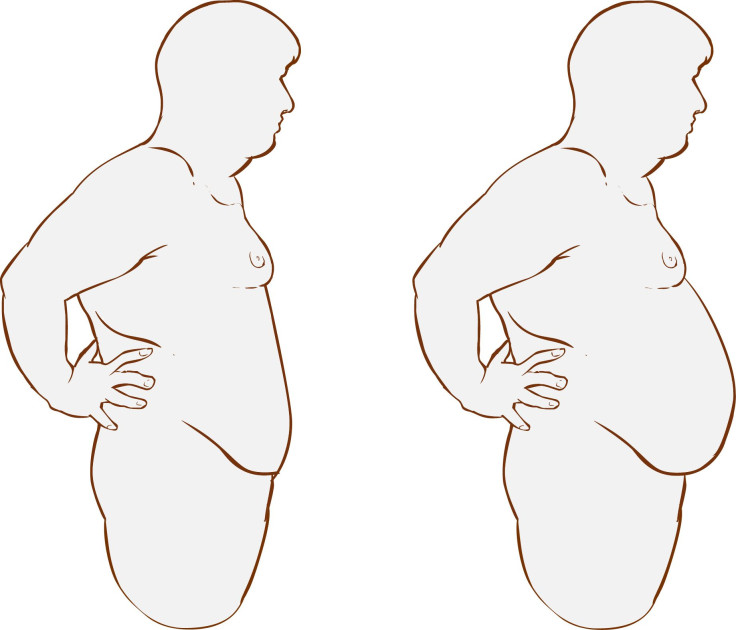

By the end of the study, the weight of the restricted diet group was similar to the unlimited diet group. However, restricted diet mice had gained more weight around their midsection. Weight around the midsection of mice was likened to belly fat in humans, which is often associated with insulin resistance and higher risk for type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

"With the mice, this is basically binging and then fasting," Belury exaplined. "People don't necessarily do that over a 24-hour period, but some people do eat just one large meal a day. Under conditions when the liver is not stimulated by insulin, increased glucose output from the liver means the liver isn't responding to signals telling it to shut down glucose production. These mice don't have type 2 diabetes yet, but they're not responding to insulin anymore and that state of insulin resistance is referred to as prediabetes."

As the study continued, mice developed gorging eating habits that caused them to finish their daily amount of food in around four hours and fast for the remaining 20 hours of the day. Gorging and fasting among mice led to a spike and then a severe drop in insulin that causes a variety of metabolic issues. Mice from the restricted diet group often experienced elevations in inflammation and a higher activation of genes that lead to the storage of fatty molecules and plumper fat cells — predominantly in the midsection.

"Even though the gorging and fasting mice had about the same body weights as control mice, their adipose depots were heavier,” Belury added. “If you're pumping out more sugar into the blood, adipose is happy to pick up glucose and store it. That makes for a happy fat cell — but it's not the one you want to have. We want to shrink these cells to reduce fat tissue.”

A similar study conducted at the Oregon Research Institute (ORI) found that skipping meals or restricting the number of calories you consume each day can actually make unhealthy food more attractive. When adolescents who willingly curbed their eating habits were shown pictures of unhealthy but appetizing food, brain imaging showed a spike in hyperactivity.

So, no matter the reason, skipping meals is depriving the body of essential nutrients.

Source: Kliewer K, Ke J, Belury M, et al. Short-term food restriction followed by controlled refeeding promotes gorging behavior, enhances fat deposition, and diminishes insulin sensitivity in mice. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com