Tetris Turns 30: Psychologists Say The Video Game Fulfills Our Desire For Order

Who knew in 1983 that Tetris would survive Michael Jackson? The venerable video game turns 30 today on what fans celebrate annually as “World Tetris Day,” a testament to the human desire for order, at least one psychologist says.

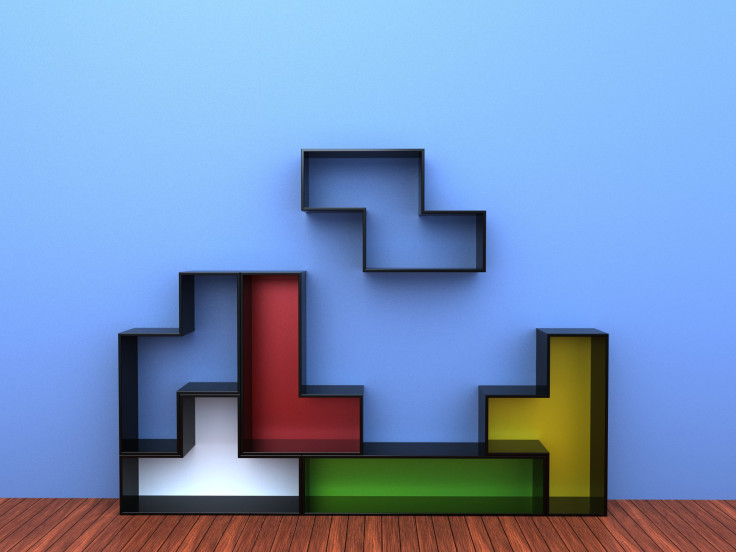

With simple graphics from the dot-matrix era of computing, Tetris challenges the player to tessellate multi-shaped bricks falling steadily downward, forever risking the asymmetry of “game over.” The vintage game tickles the brain’s basic pleasure in solving mental problems such as those presented in this “world of perpetual uncompleted tasks,” said Tom Stafford of the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom.

Essentially, the game leverages the "Zeigarnik effect": The brain is most interested in unresolved problems. “It shows how our minds are organised around goals and that our memory is not just a filing system where information is passively stored, but it adjusts dynamically according to our purposes,” he told The Courier. “It involves us in a compulsive loop of completing and generating new tasks and that keeps us endlessly playing.”

Past research on the subject shows that players solve the tasks in one of two ways. Whereas some rotate the shapes mentally to consider possible moves, most others click to rotate the shape visually for a comparison. But both methods seek to accomplish the same goal: laying multi-shaped objects onto a plane with no overlaps and no gaps.

“Tetris is pure game: there is no benefit to it, nothing to learn, no social or physical consequence,” Stafford said. “It is almost completely pointless, but keeps us coming back for more.”

True to its vintage appeal, the game originated in the former Soviet Union — with approval for export coming from the KGB. In a profile in The Guardian, programmer Alexey Pajitnov describes working for the Academy of Sciences of the USSR during that era, when he developed an interest in the rudimentary video games born early in the decade.

"I've loved puzzles ever since I was a child, especially pentominoes," he said. "In June 1984, it occurred to me that they might be a good basis for a computer game."

Thirty years after its release, the simple game has found new life on smartphones around the world as a classic application in killing time.

Published by Medicaldaily.com