The Truth About Pressure Points: Which Ones Can Kill You And Which Ones Are Just Myths

Pressure points have been present throughout pop culture; in Star Trek, Spock applied the “Vulcan nerve pinch” on the base of a person’s neck to knock them unconscious. The fictional “pinch,” Star Trek fans and writers explained, supposedly blocked blood from reaching the brain and thus caused instantaneous unconsciousness. Scientifically, of course, there’s no such thing as a “Vulcan nerve pinch” that knocks people out. Yet somehow we find ourselves clenching when someone rubs our temples too hard or a masseuse presses deep on the muscles in our neck, near our jawline.

Movies have shown us that pressing down on certain parts of the body can knock you out or even kill you — but how much of this is backed by science? There remains some confusion and controversy as to what exactly “pressure points” are, and whether putting pressure on them is good or bad. The fact is, pressure points are sensitive parts of the body that can either be used for healing or pain — whether massaged or struck, they can help you feel better, but they can also impair you. Whether or not touching pressure points can lead to death is unknown and usually dismissed by scientists but explored a little below.

Martial Arts vs. Medicine

The notion of pressure points originally began in Japanese martial arts. It was Minamoto no Yoshimitsu, a Japenese samurai who lived from 1045 to 1127, who reportedly was the first to introduce the idea of pressure points into martial arts fighting. Yoshimitsu dissected the bodies of men killed during battle in order to better understand what little spots in their body were important to either cause pain or death, if hit or touched correctly. This fine art of fighting and killing, of course, took years of training to master; not just anyone could know which angle to strike the right nerve or joint, and where and when to do it.

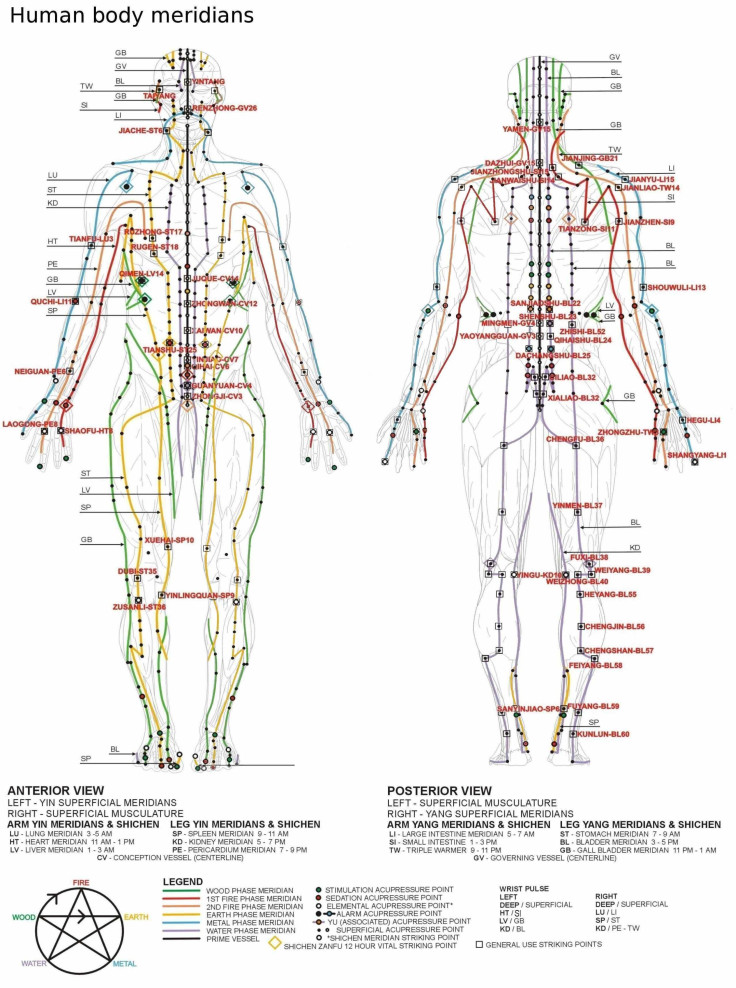

But pressure points weren’t only used for ways to kill or maim people; they were also incorporated into traditional Chinese medicine, which believes that “meridian points” are the locations in the body through which life energy, or qi, flows. Acupressure, thus, involves placing pressure on these meridian points in order to bring about better balance, circulation of fluids like blood and lymph, and metabolic energies in the body.

Critics refer to meridian points as pseudoscientific, though a 2006 study on acupressure stated that it helped reduce lower back pain. And at times, pressing or massaging certain pressure points on the body can help reduce tension headaches — which are caused by stress-induced muscle knots and jaw clenching. For example, rubbing your temples, the back of your neck, or even the webbed part in between your thumb and index finger has been shown to be helpful to relieving headache pain.

The temples and the area right below the Adam’s apple are two examples of sensitive areas that may cause pain if struck. In fighting, the goal of learning pressure points is often helpful in knowing the best places to impair an opponent rather than flat-out kill them; for example, knocking someone in the knee joint can cause their legs to crumple, or hitting the wrist at the right angle can force their hand muscles to drop their weapon.

The 'Death Touch'

But some unanswered questions remain about the most controversial so-called pressure point, what is known as the “Death Touch,” or dim mak.

“Known in Cantonese as dim mak and in Japanese as kyusho jitsu, the touch of death is said to be something like acupuncture’s evil twin,” Cecil Adams writes on his column Straight Dope. “The idea is that chi, or energy, flows through the body along lines called meridians. A blow or squeeze applied to certain pressure points on these lines will supposedly put the whammy on the victim’s chi, leading to incapacitation or death.”

Some martial artists believe that dim mak, if executed correctly, can lead to a delayed death — meaning that the pinch of an artery or meridian could lead to organ failure and sudden death after a day or two. Others believe that dim mak can simply cause instantaneous death after pressure is applied to the carotid artery or other essential spots. The stomach-9 point, for example, is believed to be a pressure point that can lead to damage of the carotid artery — which is located in the neck and essential to providing blood to the brain.

Getting knocked out is typically caused by lack of oxygen, a sudden drop in blood pressure, or blunt trauma to the brain. There is essentially little to no scientific evidence that the “Death Touch” or the pressing of other pressure points can lead to death — but it’s fair to say that certain fighting movements, like a heavy blow to the temple or an obstruction of the breathing tubes, can certainly lead to dizziness, lack of oxygen, unconsciousness — and in severe cases, death.

However, these are usually caused by losing oxygen or traumatic brain injury, not a simple touch to a pressure point. Some rare cases of trauma to the carotid artery, or even events called commotio cordis — also known as cardiac concussion, which involves a heavy blow to the chest that messes up the heart’s electrical current and leads to sudden heart failure — have brought up the question as to whether or not Japanese samurai fighters were perhaps onto something when they made claims about the “Death Touch.” But most of this remains shrouded in mystery, with more scientific studies needed to better understand it. In other words, while pressure points may exist as sensitive spots on the body that can aid in both fighting and healing, touching or pressing on them probably can't kill you. Still, use pressure points as a way to help relax your muscles, reduce tension and stress, and overcome painful headaches.

“Case reports suggest that incidents [in which pressure or trauma is applied to the carotid artery and someone dies] are mostly accidents, more often than not unrelated to martial arts training or theory,” Adams writes. “The question remains: Can some dim mak practitioners achieve these results at will? I’m skeptical, but sometimes you have to wonder.”