Vaginal Ring With Antiretroviral Drug May Protect Against HIV Infection, Especially Among Young Women

Monday, two new studies presented during the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections in Boston revealed a potential HIV prevention method for young women — and it works like standard birth control.

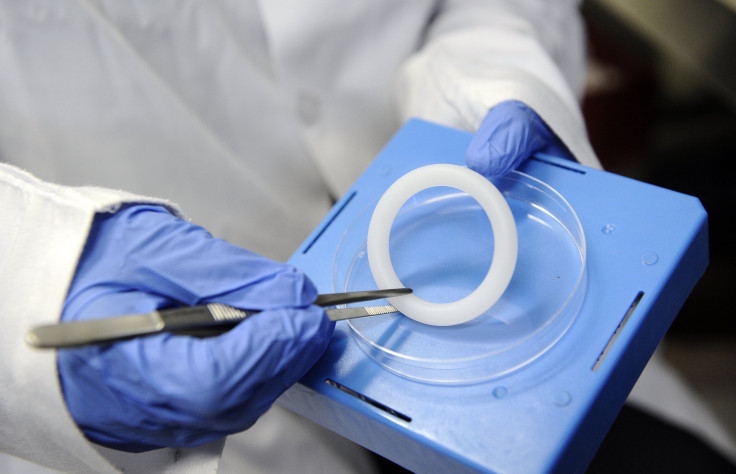

For the studies, called The Ring Study and ASPIRE, investigators are testing the efficacy of a monthly vaginal ring containing an antiretroviral drug called dapivirine. Your standard vaginal ring, like the NuvaRing, is a form of hormonal contraception, in which women are required to place a small ring in their vagina once a month for three weeks. But with this new vaginal ring, developed by the nonprofit International Partnership for Microbicides, the hormone is replaced with the antiretroviral drug. It works by blocking HIV's "ability to replicate itself inside a healthy cell."

"The vaginal ring delivers the drug directly to the site of infection, with very low systemic exposure. This, along with the ease of use, could increase the ring’s appeal for many women," Dr. Sharon L. Hillier, of the University of Pittsburgh and principal investigator of the MTN, said in a statement. "The ring could provide more options for women to reduce their own risk of HIV."

The majority of women in the Ring Study and ASPIRE were young, unmarried, and at "very high risk for HIV." The Ring Study in particular was conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa countries, which reportedly account for 70 percent of the global total. Women in each study were randomly assigned to one of two groups; one used the dapivirine ring and the other used a placebo ring.

Of the 1,300 women involved in the Ring Study, 77 acquired HIV in the dapivirine group compared to 650 in the placebo group. Similarly, in the ASPIRE group, 71 of the 1,308 women using the dapivirine ring acquired HIV compared to the 97 of 1,307 women using the placebo.

Overall, the Ring Study showed the dapivirine ring helped reduce HIV risk by 31 percent and 37 percent among women ages 21 and older. The ASPIRE study, on the other hand, showed the dapivirine ring reduced HIV risk by 61 percent in women older than 25 and 56 percent in women older than 21 compared to the placebo group.

Researchers speculated these percentage differences may have to do with the fact that women older than 21 were using the ring more consistently. Adherence was measured by dapivirine levels in women's blood plasma and residual drug left in used rings.

"This is a glass half-full moment," protocol chair of the ASPIRE study, Dr. Jared Baeten, of the University of Washington, said in a statement. "The HIV prevention field for women has struggled in the last few years — at times the glass had seemed almost completely empty. Now, for the first time, we have two trials demonstrating that a female-controlled HIV prevention method can safely help reduce new HIV infections. I'm optimistic about what these results might mean for women worldwide."

That said, little to no protection was seen among women ages 18 to 21 across both studies — and in sub-Saharan African, unprotected heterosexual sex is the primary driver of the epidemic. While protection and adherence improved over time, researchers are still "working to understand how ring use, and potential biological and other factors may have influenced the different levels of protection seen by age in these studies."

Source: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI). 2016.