On Memorial Day, A Look At How The Causes Of War Casualties Have Changed Through American History

Americans have been involved in a lot of conflicts, from the Revolutionary War to recent military excursions in the Middle East. Military technology has changed significantly in the past 200+ years of U.S. existence, and so have war medicine and the causes of conflict-related death and casualties. Until more recent decades, at least, disease and lack of proper medicine/sanitation played a huge role in American casualties. Here’s a brief history on causes of war death across some of the major wars in which the U.S. has played a part.

Revolutionary War: 1775-1783

Physicians during the Revolutionary War still held onto medical notions first proposed by Hermann Boerhaave, who believed that illness was caused by an imbalance of humors in the body. Most diseases were treated either by ingesting or draining fluid, like blood or sweat. Medical care for wounded soldiers during the war, then, was relatively primitive compared to modern standards, and most doctors were untrained or had only experienced book knowledge and never acted on real patients.

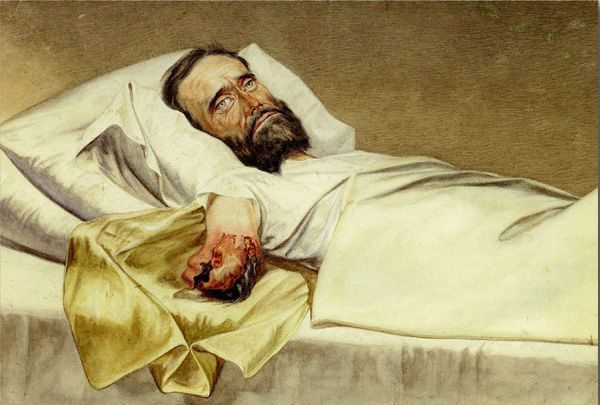

During the Revolutionary War, amputation was considered the “antibiotic of the day,” a procedure that doctors believed was the only saving grace for body parts that had been wounded or diseased. Wounds were caused by musket balls or bayonets, and it was common to save limbs with amputation — administered without anesthesia or sterilization. Soldiers had to stay awake during the procedures, only occasionally receiving rum and brandy or a wooden stick to bite down on to help them bear the pain. But because of the gruesome manner in which amputations were carried out, most patients went into shock, and only about 35 percent survived them. Infections and gangrene were common after-effects of amputations and often led to death.

There aren’t too many statistics on who died from what during the Revolutionary War, but aside from battle and medical wounds, smallpox was a major killer. The disease was so widespread, in fact, that George Washington ordered mandatory inoculation (the primitive version of vaccination) for all troops, hoping to prevent infantries being wiped out. And south of New England, malaria was especially destructive.

“The most feared ailment north and south, however, was smallpox, which could be both disfiguring and fatal,” PBS writes. “The roughened skin of facial smallpox scars were a common sight in Revolutionary America, although artists tended to render these blemishes as rosier-than-normal cheeks in portraiture of the time.”

Civil War: 1861-1865

The Civil War was the single most deadly conflict in American history, claiming the lives of around 625,000 people throughout the course of four years. That number accounted for 91.2 percent of total American war deaths in the first 100 years of U.S. existence.

Of the casualties that occurred during battles, 50.6 percent were committed by muskets, or light guns with long barrels fired from the shoulder. Around 5.7 percent of soldiers were wounded or killed by cannon fire, and others were taken down by pistols, sabers, and bayonets. Still, some 42.1 percent of soldiers died due to unknown causes during battles, or likely a combination of all the others.

But the greatest killer during the Civil War was disease. In fact, two-thirds of the 625,000 casualties — around 400,000 — died of disease, not injuries. Most soldiers died of dysentery, or infectious diarrhea, which caused intestinal inflammation and bloody diarrhea. Other common diseases that wiped out large populations of infantry included typhoid fever, ague, yellow fever, malaria, scurvy, pneumonia, and smallpox. These diseases spread easily through camps primarily due to poor hygiene, reusing dirty pots to cook food, garbage in camps, overcrowding, and contaminated water.

In addition, disease was widespread during the Civil War era because medicine still hadn’t caught up with warfare technology; germ theory hadn’t developed yet, and doctors were rare and untrained. A common, misguided technique was to transfer pus from one person’s infection to another, thinking it was a sign of healing; or quick-and-dirty amputations. This led to rampant infections that killed plenty of soldiers, as the notion of keeping things sanitized to avoid bacterial spread still hadn’t been fully accepted. As George Worthington Adams, author of Doctors in Blue: the Medical History of the Union Army in the Civil War , wrote: “The Civil War was fought in the very last years of the medical middle ages.”

World War I: 1914-1918

World War I was the turning point for wartime medical treatment. Not only had war technology advanced from muskets to machine guns and artillery, but medicine had finally moved forward as well. In general, there were more doctors involved in the war, who were better trained and equipped than ever before.

Compared to past wars, when amputees or patients who had been shot would die from loss of blood, doctors during WWI had figured out a way to transfuse and store blood for emergency surgeries. In 1917, Captain Oswald Robertson, a U.S. Army doctor, started the first blood bank on the Western Front. Being able to provide wounded soldiers with blood on the battlefield was a game changer. In addition, while the discovery of antibiotics didn’t occur until 1928, doctors were already experimenting with antiseptics during WWI, sanitizing wounds to prevent infection.

As battle wounds were more efficiently tended, the spread of disease among soldiers was dropped significantly. The typhoid vaccine, for example, reduced the number of typhoid cases from 20,000 during the Spanish-American War (1898) to only 1,500 in WWI. But that doesn’t mean that soldiers in the trenches were protected from everything: Many suffered from trench foot, caused by standing in water for a long time and losing circulation, or having socks grow into their skin; trench fever, which was caused by lice; and shell shock, a mental disorder caused by the loud explosions and chaos of battle.

World War II: 1939-1945

World War II sped up medical advancements even more: “If any good can be said to come of war, then the Second World War must go on record as assisting and accelerating one of the greatest blessings that the 20th Century has conferred on Man — the huge advances in medical knowledge and surgical techniques,” Brian J. Ford wrote. “War, by producing so many and such appalling casualties, and by creating such widespread conditions in which disease can flourish, confronted the medical profession with an enormous challenge — and the doctors of the world rose to the challenge of the last war magnificently.”

Battle deaths from gunshot wounds, bombs, gas, or injuries as well as accidents and diseases played a role in American war deaths in WWII. But medical advancements, like the use of Penicillin and vaccination, drastically changed both the way soldiers were treated and survival rates. Still, WWII ended up being the deadliest war in world history, though it ranked second in American casualties next to the Civil War.

Penicillin was one example of a medical advancement that didn’t fully take sail until triggered by the war. An urgent need for mass production of the antibiotics spurred companies to start making them on an industrial scale. It saved countless lives from gangrene and infections, bolstered by the first skin grafts used in war. Tetanus immunization, which had already begun to take hold during WWII, was refined into even more effective vaccination.

Vietnam War: 1955-1975

It was during the Korean War and Vietnam War that emergency field medicine made bounds forward. The use of helicopters increased a wounded soldier’s chance of getting medical help before it was too late. In 1969, nearly 200,000 casualties were transported to hospitals through helicopters, reducing the time of waiting to get treatment from 1-2 hours to under 40 minutes. Vietnam also spurred the start of Mobile Army Surgical Hospital (MASH) units, which consisted of a fully functional hospital that would bring experienced surgeons closer to the front. This served as a highly successful alternative to field and general hospitals in WWII, with severely wounded soldiers cared for at a MASH unit having a 97 percent chance of survival. Whereas before soldiers were dying from untreated wounds, infection, or waiting too long before treatment, now soldiers were mostly dying from immediate impact bombs or gunshots. Wounded soldiers had a decent chance at survival.

Disease, however, still remained rampant in the jungle. According to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), 70.6 percent of hospital admissions were disease-related, with battle casualties only making up 15.6 percent. Environmental hazards like pesticide and herbicide spraying put troops at risk, and the tropical weather/humidity led to many cases of jungle rot, which consisted of skin lesions caused by dampness-related infections. Other tropical diseases like malaria and diarrhea affected thousands of soldiers. Fortunately, “ the good survival rates seen were attributed to rapid evacuation, the ready availability of whole blood and well-established semi-permanent hospitals,” the VA states.

The VA also notes that many of the causes of death for Vietnam War soldiers occurred years after the war. Due to Agent Orange and other herbicides used in Vietnam, there are eight VA-recognized cancer conditions that are considered to be related to military service during the war: soft tissue sarcoma, non-Hodgkins lymphoma, Hodgkin’s disease, chloracne, porphyria cutanea tarda, respiratory cancers, prostate cancer, and others.

But perhaps the greatest impact of the Vietnam War on American soldiers wasn’t physical, but mental and emotional. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a lack of support on the home front, and a growing drug and substance abuse problem among troops were major problems for American troops during the Vietnam War, leading many to suffer from mental illness and even commit suicide years later. In fact, PTSD wasn’t even fully recognized until after the Vietnam War. It’s well-known that Vietnam War veterans have a much higher risk of suicide than the general population, with tens of thousands having committed suicide since returning from the war. It appears that the Vietnam War was one of the turning points in which wounded soldiers were surviving and living longer, but the main war-related killers didn’t show up until years later.

Afghanistan/Iraq: 2001-2012

Like every past war, the most recent American wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have also led to advancements in combat medicine and trauma care. “There is no doubt” that it has, Dr. Vikhyat Bebarta, interim director of the U.S. Air Force Enroute Care Research Center, told Medscape in an interview. “Mortality is the lowest in the history of war. Armor and vehicles have a lot to do with it, but it also has to do with the clinical care we are providing. We have changed the way combat medicine is delivered.”

Some of that involves the use of tourniquets, the critical care air transport team, ultrasound and intraosseous needles, and improved treatment of blast injury.

In a 2004 study, researchers measured how much a difference medical care made in soldier survival rates. They found that as casualties and war technology increased over time, so did survival rates. “ Though firepower has increased, lethality has decreased,” the authors wrote.

They continued: “In World War II, 30 percent of the Americans injured in combat died. In Vietnam, the proportion dropped to 24 percent. In the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, about 10 percent of those injured have died. At least as many U.S. soldiers have been injured in combat in this war as in the Revolutionary War, the War of 1812, or the first five years of the Vietnam conflict, from 1961 through 1965. This can no longer be described as a small or contained conflict. But a far larger proportion of soldiers are surviving their injuries.”

However, the psychological and substance abuse that surfaced after the Vietnam War continues today. The most lethal effects of combat now appear to be mental illness, opioid abuse, and suicide, another reason why Memorial Day should be about both giving American soldiers our thanks — and recognizing how much we owe them when it comes to proper care and treatment.