Wasabi And Tear Gas Are Teaching Scientists About Pain Medication Development

Thanks to a high-resolution imaging technique, scientists working with compounds in pain medication are now able to create a 3D image of the so-called “wasabi receptor,” a protein that acts as a gatekeeper for ions that trigger pain signals. Now that they can see how the protein is structured, they can develop smarter compounds to stop pain more effectively.

Current pain medications either work through blocking the brain’s perception of pain or limiting the signal itself by targeting inflammatory responses. When the nerve cells detect a chemical signal, either from outside agents like wasabi and tear gas or from within the body, various chemical processes send fluid to the pain site to act as a cushion. This is the inflammation. The wasabi receptor, formally known as TRPA1 (pronounced “Trip-A1”), senses these responses and opens. Unfortunately, the research into TRPA1 hasn’t been able to see how it opens in sufficient detail, so developing pain drugs has largely been a game of guess and check.

“We've known that TRPA1 is very important in sensing environmental irritants, inflammatory pain, and itch, and so knowing more about how TRPA1 works is important for understanding basic pain mechanisms,” said Dr. David Julius, co-author of a new study and physiology professor at the University of California, San Francisco, in a statement. With the enhanced technique, called electron cryo-microscopy (cryo-EM), Julius and his team were able to view the TRPA1 receptor at a resolution of about four angstroms. For perspective, one angstrom is equal to one 10-billionth of a meter.

“This provides important insight into how this one major class of drugs interacts with TRPA1 and thus how it may work to block channel function,” Julius said.

Prior use of cryo-EM had yielded disappointing results. For years, the finest detail scientists could achieve was a resolution of about 15 angstroms. The pictures were far too coarse to make out important molecular structures, leading some scientists to dub the method “blob-ology.”

In 2013, however, Julius and his latest co-senior author Dr. Yifan Cheng, an associate professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UCSF, published a study in Nature showing cryo-EM could faithfully pick up a related ion channel called TRPV1. According to Cheng, the findings “sent shockwaves through the field of structural biology.” The technology was longer doomed to the unhelpful realm of fuzzy images. So, the team set their sights on TRPA1.

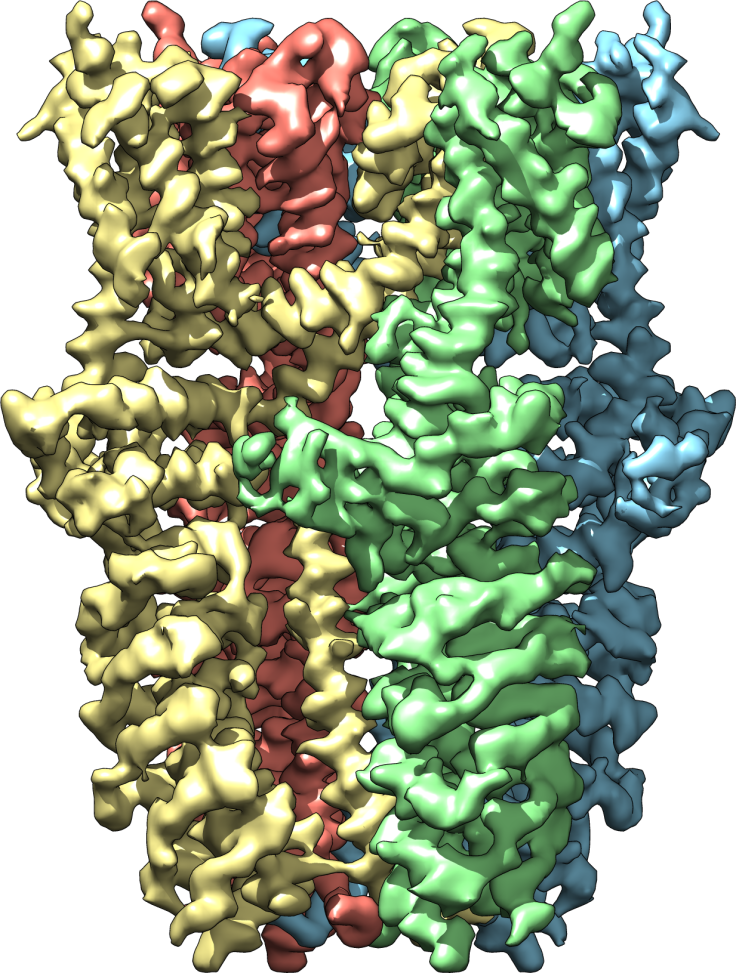

In their study, the team extracted the desired proteins and froze them in a thin sheet of glassy ice. They took some 100,000 pictures of the proteins, so that eventually they could assemble the 2D images into a 3D rendering. The new picture shows the protein in three different states: open, partially open, and closed. From the new perspective, they can see exactly which channels let ions through — a development that could facilitate much quicker production of pain-relieving medication.

“Cryo-EM has undergone a ‘resolution revolution’ that has enabled us to literally see TRP channels in all their glory,” Julius said. “We've had some idea what TRPA1 might look like, but there's something elegant and satisfying about obtaining the structure, because seeing really is believing.”

Source: Julius D, et al. Nature. 2015.