What Is Chemotherapy? The Ins And Outs Of Treatment, And How It Affects Cancer Patients

Chemotherapy dates back to World War II when, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS), the U.S. Army was studying a compound called nitrogen mustard. When this compound effectively worked against cancers, such as lymphoma and acute leukemia, researchers focused on discovering “drugs that block different functions in cell growth and replication.” Thus, chemotherapy was born.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that about 650,000 cancer patients receive chemo in outpatient oncology clinics in the U.S. each year. Yet, as commonplace as it is, and as much as researchers have learned of it since its initial debut, most people would struggle to tell you exactly how this cancer treatment works. Just how many chemo drugs are there, and is there a drug for every kind of cancer? Dr. Nimmi Kapoor, a surgical oncologist with RADNET, helps us break it down.

Attacking Cancerous Cells

Kapoor’s basic definition of chemotherapy is, “Medication given through the vein" that "often involves a combination of drugs that halt the growth of dividing cells.” Most treatments are adminstered intravenously, but there are cases where it's adminstered through an inserted catheter or port to lessen bruising, tissue damage, and make it possible to be treated at home. Since “cancerous cells are typically dividing fast,” she said chemo ultimately works to slow or stop their growth.

It’s estimated there are over 100 different kinds of these drugs today, possibly more as new drugs are regularly introduced. One subset of medication is known as immune-modulators, which Kapoor said helps “work with a patient’s own immune system while attacking cancerous cells.”

Other types of chemo drugs include alkylating agents, anti-tumor antibiotics, and corticosteroids (or simply steroids). Most drugs work to directly stop cells from reproducing, while others target the side effects of chemo.

Severe Side Effects

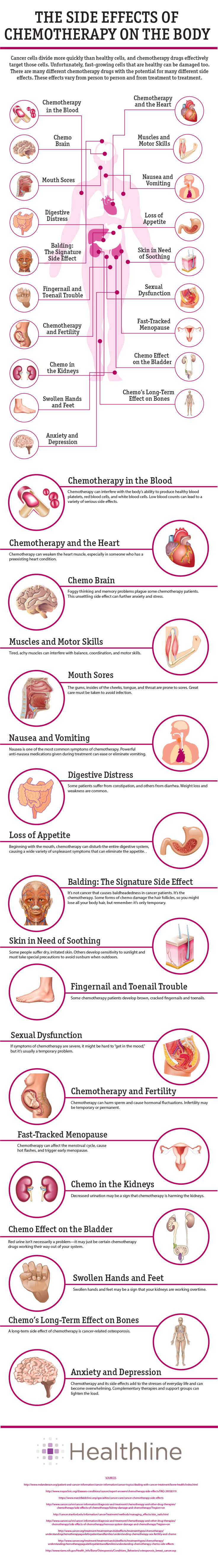

Hollywood does a pretty good job of portraying what cancer patient’s encounter during their sessions of chemo, such as hair loss, nausea, and life-threatening neutropenia, which means a person’s white blood cell count is so low they can’t fight off infection. The ACS would also add anemia, appetite loss, diarrhea, mouth and throat problems, and skin and nail changes among several others.

It’s important to note not every patient will have the same reaction to treatment.

“Everyone responds differently and some lucky patients can even hold a full-time job while undergoing treatment,” Kapoor said. “The biggest advances in chemotherapy in the last two decades have been the drugs available to combat some of the severe side effects.”

The aforementioned class of steroids can be helpful in deterring the nausea and vomiting that often comes with treatment — even allergic reactions. Other studies suggest vitamin C, exercise, and acupuncture may also help to alleviate side effects of treatment.

|

Which Patients, And Which Tumors Will Benefit

When chemo is effective, it can prolong a patient’s life for months to years, and even decades, Kapoor said. But at the same time, chemo isn’t for all patients and all cancers. Current cancer research is focused on this reality; on finding out which patients and which tumors stand to benefit the most from these drugs.

“Some breast cancers and the majority of all thyroid cancers, for example, do not need any chemotherapy, whereas the main treatment of blood cell cancers, such as leukemia and lymphoma, require very specific chemotherapy regimens,” Kapoor said. “Chemotherapy regimens can often consist of multiple drugs given in a variety of combinations. Over years of research and clinical trials, the type, order, and frequency of drug combinations for various cancers have been studied and improved for the best survival outcome with the least toxicity.”

The toxicity attached to chemo drugs is why some eligible patients refuse it in the first place. In the case of Connecticut teen Cassandra Fortin, the court deemed her too young to make a decision and ordered her into treatment. Though today Fortin is in remission, she explained on her Facebook she will never be OK with all that’s happened to her.

That said it’s not uncommon for prescribed rounds of chemo to be unsuccessful. One study found chemo can trigger healthy cells to secrete a protein that sustains, rather than inhibits cancer cell growth. And a separate study found some cells aren’t susceptible to chemo, especially in cases of acute myeloid leukemia.

Treating the Whole Person

Given the nature of chemo, patients might also be prescribed additional treatment and therapy in order to increase their chances of survival. Chemo is a “systemic therapy,” or a therapy that target’s the patient’s entire body, whereas other, local therapies, like radiation, focus directly on one area of the body.

“Typically,” Kapoor said, “radiation is focused external beams from a high-energy source directed to the area of cancer occurrence (or in some cases recurrence), such as the prostate gland, brain, or breast. The side effects of radiation are typically only local issues, such as a sunburn to the breast, swelling of a gland, irritation of local tissues and not [the] ‘whole body’ effects that you may get with [chemo].”

Patients should know local therapy has nothing to do with the type of systemic therapy they may need or get. Kapoor herself often reminds her patients that “oncologists focus systemic therapy on the biology of the tumor, and this may determine if patients may need, for example, a year of Herceptin-based chemotherapy followed by five years of tamoxifen for [hormone-driven] breast cancer.”

Continued Progress

Cancer sucks, and patients require a personalized approach to treating their specific cancer and their specific body. We have a good grasp on the general knowledge and side effects of treatments, like chemo, with most people agreeing the benefits of chemo outweigh the risks, but there’s still a lot we can learn (despite already coming so far since this era of treatment began).

“The approach to patient treatment has become more scientific with the introduction of clinical trials on a wide basis throughout the world,” the ACS reported. “Clinical trials compare new treatments to standard treatments and contribute to a better understanding of treatment benefits and risks. They are used to test theories about cancer learned in the basic science laboratory and also test ideas drawn from the clinical observations on cancer patients. They are necessary for continued progress.”