What Does Marijuana Do To Your Brain And Body? THC Interacts With Memory, Time Perception

As more and more state lawmakers consider the pros and cons of decriminalizing or legalizing marijuana, the science surrounding the drug runs a constant risk of becoming politicized. For this reason, it may be in everyone’s best interest to review what we currently know about America’s favorite illegal thing.

To do this, we will look at delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC — the active ingredient in cannabis. This chemical interacts with a wide range of systems, giving rise to an equally wide range of effects. The “high” is therefore a pretty diverse one, with users reporting everything from euphoria and calm to paranoia and anxiety.

Cannabinoid Receptors

When you smoke marijuana, THC passes from the lungs to the bloodstream, where it is eventually picked up by two types of receptors — cannabinoid receptor (CB) 1 and 2. These long, rope-like proteins weave themselves onto the surfaces of cells all over the body, which helps explain increased heart rate, red eyes, pain relief and other effects that are not purely psychological.

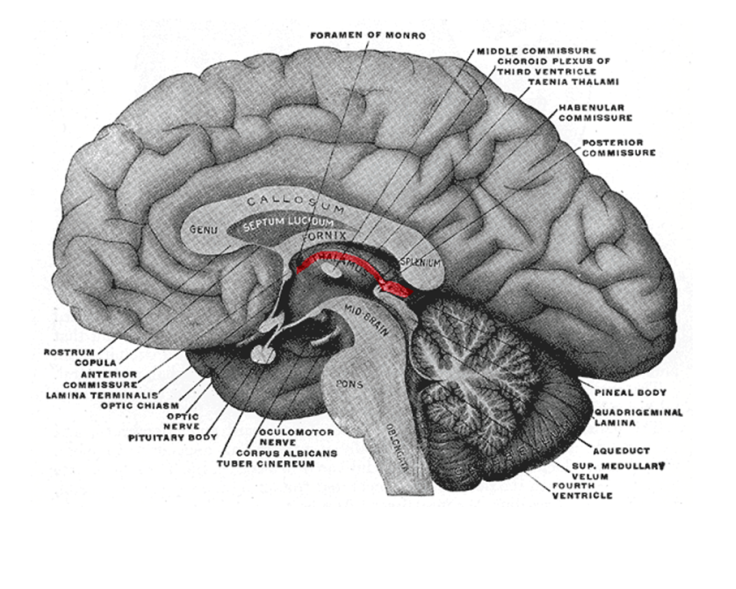

That said, most of the action takes place in the central nervous system, where THC is carried by CB1. Here, the compound typically has about two to four hours to toy with a range of neurological functions — including, but not limited to, memory formation, appetite, and time perception.

Memory

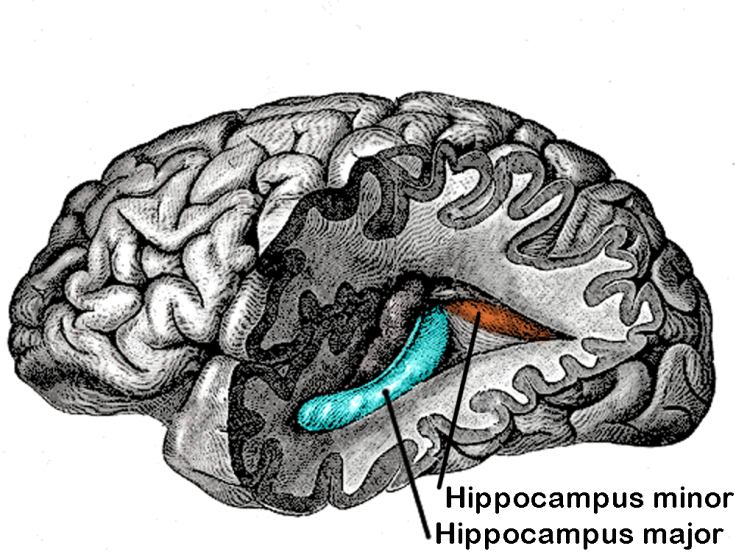

Numerous studies have examined the ways in which marijuana inhibits short-term memory formation. Most point to disrupted activity in the hippocampus — the brain area thought to control working memory. Because the hippocampus contains so many cannabinoid receptors, it is rapidly weakened during marijuana use.

Although these memory problems are typically considered temporary, a 2013 study from Northwestern University found that heavy users who start in their teens may develop structural abnormalities in certain brain areas. “The study links the chronic use of marijuana to these concerning brain abnormalities that appear to last for at least a few years after people stop using it,” lead author Matthew Smith wrote.

Hunger

The hippocampus is far from the only brain center affected by THC. As most stoners inevitably know, the compound also riles up the hypothalamus — that is, the area of the brain tasked with regulating appetite. For users who are otherwise healthy, this does little more than promote excess weight gain. However, for patients struggling to gain weight, this particular side effect can be indispensable.

In a study published in 2011, researchers from the University of Alberta in Canada found that marijuana may help cancer patients whose appetite and sense of smell has been impaired by the disease. "This is the first randomised controlled trial to show that THC makes food taste better and improves appetites for patients with advanced cancer, as well as helping them to sleep and to relax better,” lead author Wendy Wismer explained. “We are excited about the possibilities that THC could be used to improve patients' enjoyment of food.”

Time

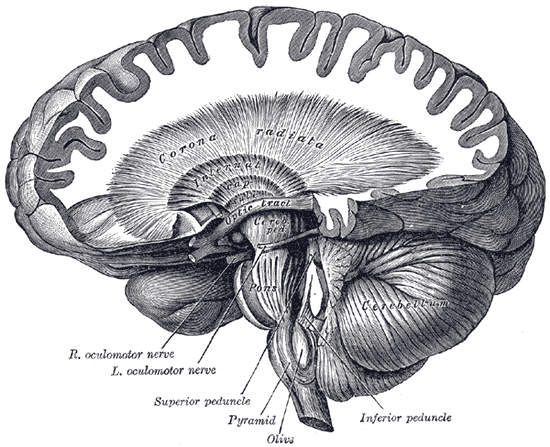

A distorted sense of time is one of the most frequently reported effects of marijuana among users. In one study from 1998, researchers used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine that this side effect may stem from altered blood flow to the cerebellum, which has been linked to an internal timing system.

“There was a significant increase in cortical and cerebellar blood flow following THC, but not all subjects showed this effect,” the authors wrote. “Those who showed a decrease in cerebellar CBF also had a significant alteration in time sense.”

Published by Medicaldaily.com