What Happens In Your Brain When You Have A Panic Attack? How The Brain’s Fear And Threat Centers Backfire

It happens to the best of us: an onslaught of emotions that quickens your heartbeat, cranks up perspiration, and blurs vision. A feeling that this, for better or worse, is it, and that you are now going to die.

Panic attacks are, according to health experts, exceedingly common. Some experience them once or twice in their lifetime; others have them whenever they’re speaking in public or preparing for an important phone call. In severe cases, sufferers may feel like they’re choking or coming close to fainting.

Aside from pharmacological solutions, the best way to conquer panic attacks is to make each episode your friend — but in order to do so, it is important to have a handle on what this phenomenon is all about, neurologically speaking. When the lights begin to go out, what’s really happening in your brain?

Panic Attacks and the Brain

As with anxiety, paranoia, depression, and other clinical terms that have entered everyday language, a panic attack can mean different things to different people. It may for this reason be useful to settle on a working definition before we go any further. The folks at Mayo Clinic, who usually know what they’re talking about, define a panic attack as: “A sudden episode of intense fear that triggers severe physical reactions when there is no real danger or apparent cause. Panic attacks can be very frightening. When panic attacks occur, you might think you're losing control, having a heart attack or even dying.”

This is how we will think about panic attacks as we try to unravel the brain chemistry that underpins them: brief spells of intense, visceral fear. The kind of fear that keeps you violently alive in the face of danger.

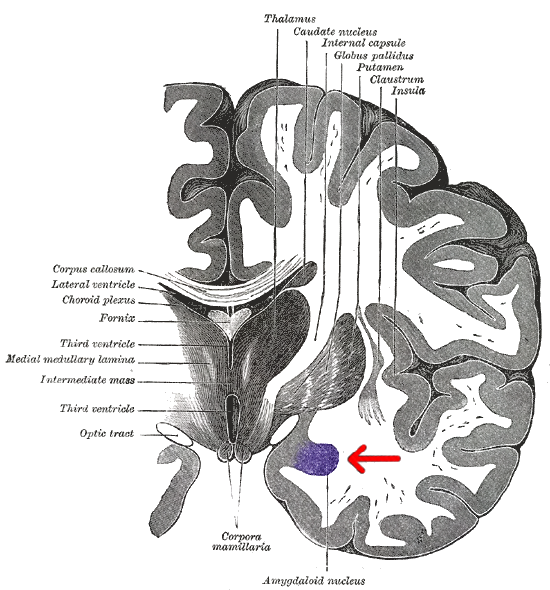

Here’s a layout of the brain region that contains the amygdala. The amygdala, which is made up of compact neuron clusters, is understood to be the integrative center for emotions, motivation, and emotional behavior in general, but is perhaps best known for its role in fear and aggression.

One theory of panic attacks and panic disorder is that they both stem from abnormal activity within this cluster of nerves. In a review of existing research published in 2012, Dr. Jieun E Kim and his colleagues cite several animal studies that link stimulation of the amygdala to behavior analogous to human panic attacks.

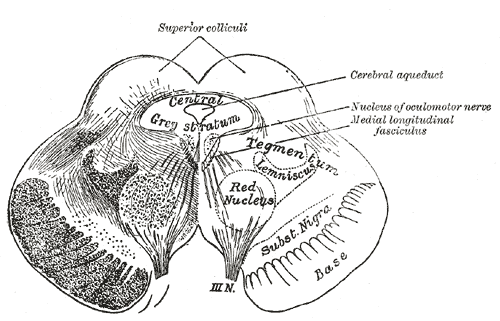

Writing for Scientific American, Dr. Paul Li of the University of California, Berkeley, offers another possible culprit: a midbrain section known as the periaqueductal gray, which regulates defense mechanisms like running or freezing. In one study, functional MRI scans found that this area lights up with activity in response to imminent threats.

“When our defense mechanisms malfunction, this may result in an overexaggeration [sic] of the threat, leading to increased anxiety and, in extreme cases, panic,” Dean Mobbs, a researcher at Columbia University and lead author of the study, explained.

What To Do About It

Symptoms that arise from this type of brain activity can typically be treated with medication. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), for example, are frequently prescribed for people who suffer from persistent panic attacks and anxiety. However, psychotherapy can also be very effective, as it teaches you to separate panic sensations from threat responses.

In addition, simple lifestyle adjustments can have tremendous benefits. Sufferers often find comfort in physical activity, sufficient rest, relaxation techniques like yoga, as wells as talking to others with similar problems.

Published by Medicaldaily.com