What's In Secondhand Smoke? Lead, Formaldehyde, Ammonia, And 7,000 Other Chemicals

It’s pretty easy living in New York City to find yourself walking among a crowded group of people, with the one or two in the front puffing away on their cigarettes, and blowing smoke in your face. For those who don’t smoke cigarettes, the smell alone is unbearable. For children whose parents smoke in their home, the smell is extra potent, and in both cases, children and bystanders are inhaling some pretty nasty stuff. Secondhand smoke, essentially, is just as bad as the smoke someone inhales when taking a drag of their cigarette.

Whether it’s from cigarettes, cigars, or pipes, secondhand smoke is categorized as either the smoke that comes off the lighted end of the product (sidestream smoke) or the smoke exhaled from the smoker’s mouth (mainstream smoke), according to the American Cancer Society. They’re two different things, but both dangerous. Due to its passing through the smoker’s lungs, mainstream smoke tends to be a little less toxic, as at least some carcinogens are filtered out.

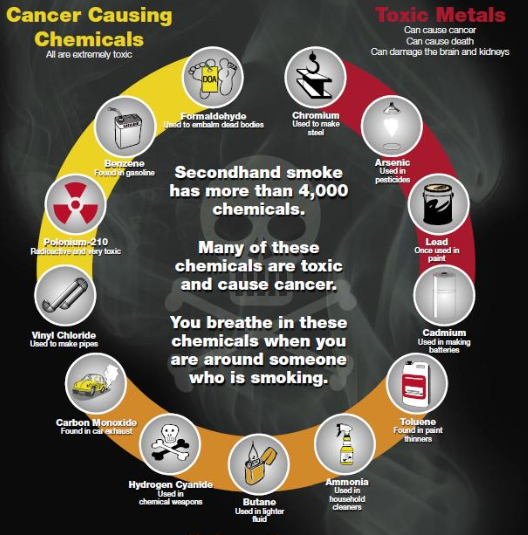

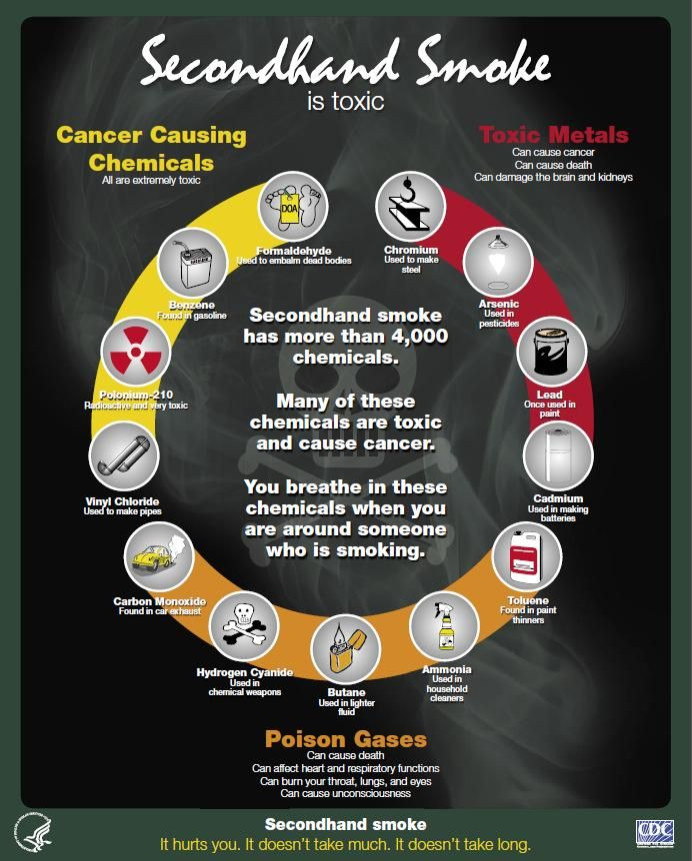

Either way, both contain harmful amounts of various substances that will make you want to hold your breath the next time you pass by someone smoking.

That’s only a snapshot of the substances, however, as there are anywhere from 4,000 to 7,000 chemicals, of which hundreds are toxic, and 70 have been found to cause cancer, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Since 1965, 2.5 million nonsmokers have died from secondhand smoke, and that’s not counting the thousands of others who developed heart disease, stroke, and lung cancer. Besides the obvious (cardiovascular disease, stroke, and cancer), secondhand smoke exposure has been linked to increased risk of hospital asthma readmissions, type 2 diabetes, and aggressiveness and antisocial behavior in kids.

Since 1965, when smoking rates were near their highest, with 42 percent of adults inhaling the toxic chemicals, secondhand smoke exposure has gone down. The CDC’s data shows that between 1988 and 2008, exposure to secondhand smoke dropped from 88 percent to 40 percent. Those rates illustrate the speed at which smoking is being stifled, as more people learn of the health risks associated with the products.

State governments are increasingly implementing new laws to help those who don’t smoke to avoid exposure. As of April 2014, 24 states and the District of Columbia required all non-hospitality workplaces, restaurants, and bars to be 100 percent smoke-free. Some local governments have even begun implementing laws banning smoking in public parks and beaches, such as in New York City.

Published by Medicaldaily.com