Age Progression Software Is So Good People Can’t Tell The Difference Between Real Photos And Mock-Ups

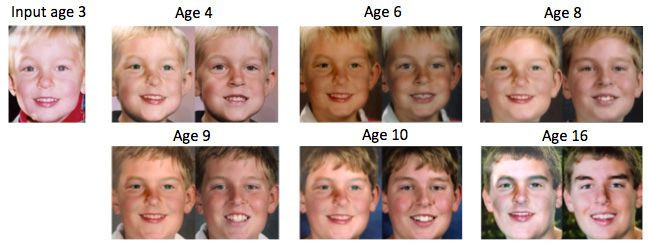

It might as well be fortune-telling: Scientists at the University of Washington have developed a piece of age progression software that can so accurately predict how a person will age that when people were asked to discern between real and fake photographs, they might as well have been flipping a coin.

The team’s study, to be presented at the IEEE Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition conference in June, has far-reaching implications for parents and law enforcement trying to locate missing children, especially those who haven’t been seen for years. Current technologies offer a passable likeness, but they require a lot of time to generate a rendering. The latest software can produce a lifetime of faces in 30 seconds.

Among the other challenges for the current technology is capturing long-term resemblances from portraits under five years old. Babies naturally share more common features than older people, before their skulls concretize and their jaws pronounce. Researchers are confident they can take a picture of a teenager or an infant and create an equally accurate rendering for both.

“Aging photos of very young children from a single photo is considered the most difficult of all scenarios, so we wanted to focus specifically on this very challenging case,” said Ira Kemelmacher-Shlizerman, UW assistant professor of computer science and engineering, in a statement. Part of that challenge is using candid photographs, not posed portraits, to generate a future likeness. Seldom are kids captured in the optimal light or position, adding an extra layer of difficulty to the team’s project.

Ultimately, their software ended up with thousands of photos on file, each used in some capacity, depending on age and gender, to create a composite image of the target subject as he or she ages. An algorithm the team developed culls the correct details from each bracket written into the software and assembles them into a full image, adjusted for lighting cues, wrinkles, and facial shape. They then took these rendered images to 82 study participants to test their authenticity.

Participants were given several options when it came to interpreting the pictures in front of them. They could choose which of the two was the researchers’ concoction, which one was real, if both were real, or if neither was real. In the end, subjects chose the researchers’ approximately 37 percent of the time, the real one 44 percent of the time, both 15 percent of the time, and neither five percent of the time.

“Our extensive user studies demonstrated age progression results that are so convincing that people can’t distinguish them from reality,” said co-author and UW professor Steven Seitz.

Up next for the research team is advancing the software’s wrinkling and hair whitening capabilities, not to mention including other ethnicities. “I’m really interested in trying to find some representation of everyone in the world by leveraging the massive amounts of captured face photos,” Kemelmacher-Shlizerman said. “The aging process is one of many dimensions to consider.”