Alzheimer’s Disease Early Diagnosis: Eye-Tracking Tests Could Help

Eye-tracking tests to detect Alzheimer’s entered the realm of possibility this decade with the development of visual screening tests for this incurable disease. All these different types of tests share one aim: finding a better way to diagnose Alzheimer’s in its early stages.

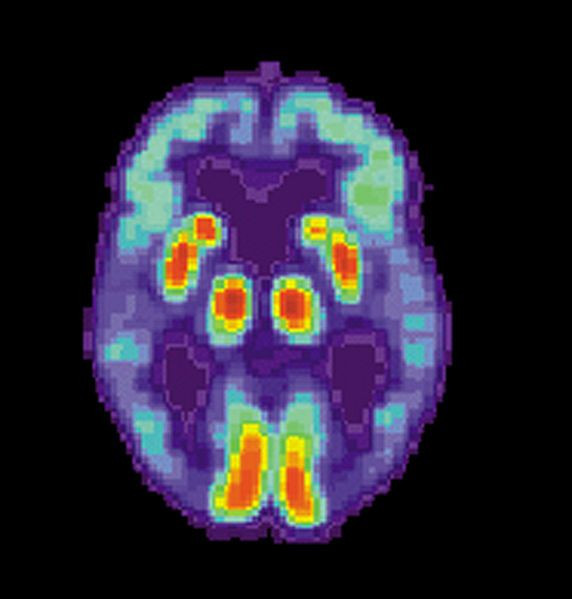

Most Alzheimer's patients are diagnosed after a detailed medical exam and extensive tests that determine mental function. Other tests can detect signs of Alzheimer’s and help pinpoint the preclinical window for therapeutic intervention. These tests such as spinal fluid analyses and positron-emission tomography (PET) scans are, however, both difficult and very expensive.

As yet, there is no cheap, fast, non-invasive test that can accurately identify people at risk of Alzheimer's.

On the other hand, a number of studies reveal people with Alzheimer's show signs of eye movement impairment before any cognitive symptoms appear. For one, a person’s inability to direct his gaze in the appropriate direction is often present at the very early stages of Alzheimer's. Standard eye tracking tests can reveal this sign of dementia.

In the new study, researchers set out to accurately detect people with a form of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) that predisposes them to Alzheimer's. MCI is a small decline in memory and reasoning, not serious enough to interfere with a person’s daily activities. It is, however, apparent to the person who develops the condition.

It’s well known Alzheimer's often evolves from MCI. Some studies suggest 46 percent of people with an MCI diagnosis developed dementia within 3 years. By comparison, only 3 percent of adults of the same age experience Alzheimer's during the same time span.

MCI has two forms: amnesic (aMCI) and nonamnesic (naMCI). The former refers to impairment that predominantly affects memory; the latter affects other cognitive skills.

Having aMCI increases the risk of Alzheimer's significantly more than naMCI.

This means detecting Alzheimer's as early as possible improves a person's brain health. It might also reduce their symptoms, especially if a reversible form of MCI is the cause.

Researchers at the School of Sports, Exercise, and Health Sciences at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom embarked on a project to develop an accurate method of diagnosing the subtypes of MCI.

Led by Thom Wilcockson, the team set out to use eye tracking technology to distinguish between aMCI and naMCI.

Analysis of the data involving more than 250 participants revealed it was possible to distinguish between the participants who had aMCI and those who had naMCI from their eye tracking results. In additoin, the eye tracking results of persons with aMCI closely resembled the scores of those with full blown Alzheimer's.

"The work provides further support for eye tracking as a useful diagnostic biomarker in the assessment of dementia," said the authors of this first-of-its-kind study in the journal, Aging.

"Given that people with MCI are more likely to develop dementia due to [Alzheimer's] than cognitively healthy adults, and, in particular, that people with [aMCI] are at the highest risk of progressing to a full dementia syndrome, this may also offer an additional prognostic tool for predicting which people with a diagnosis of MCI are more likely to progress to [Alzheimer's]."

Published by Medicaldaily.com