Anti-HIV Vaginal Ring May Be on the Horizon

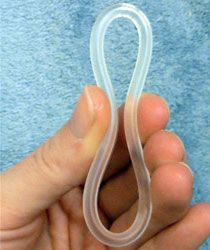

Researchers from the Center for Biomedical Research in New York, Rockefeller University in New York, Tulane University in Louisiana, and the National Cancer Research Institute in Maryland have developed a vaginal ring that can prevent transmission of HIV.

In the study, female macaque monkeys either received a vaginal ring with anti-HIV medication or a ring with a placebo. Then, researchers inserted both HIV and SIV, the primate equivalent of HIV, into the monkeys' vaginas through use of a catheter. The rings were either inserted two weeks or 24 hours before HIV and SIV were introduced to their systems.

Of the monkeys with the anti-HIV vaginal ring, two out of 17 monkeys, or 11.7 percent, contracted HIV. Comparatively, of the monkeys with the placebo, 11 of 16 monkeys, or 68.7 percent, became infected. That means that the ring was 83 percent more effective at preventing the disease than the placebo was.

The vaginal ring contained an anti-retroviral drug called MIV-50 and was effective whether the rings were inserted two weeks or 24 hours before contracting the virus. But researchers say that the vaginal ring needs to be inside the body in order for it to work. When they removed the ring just before they inserted the virus, 4 out of 7 monkeys contracted the disease, marking an infection rate of 57 percent.

The concept of a vaginal ring is not a new one. A vaginal ring called NuvaRing is on the market today and is used as birth control.

Oral antiretroviral drugs, microbicide gels, and condoms can be used to effectively prevent transmission of HIV. But antiretroviral drugs need to be taken daily in order to be effective, gels need to be applied every time a person has sex, and women are not always able to make a man put on a condom. Doctors were hoping to create a tool that a woman can leave in for three months without worrying about its efficacy.

Researchers hope that the ring can also be used to prevent against other sexually transmitted infections, such as herpes and the human papillomavirus (HPV).

They hope to conduct a human trial in as little as two years.

The study was published in a recent issue of Science Translational Medicine.