Artificial Jellyfish Creation Raises Possibilities of Manufactured Organs

Scientists have created an artificial jellyfish using heart cells from rat and a thin sheet of silicone.

The scientific team from Harvard University and California Institute of Technology, that created the artificial jellyfish, has named it "medusoid."

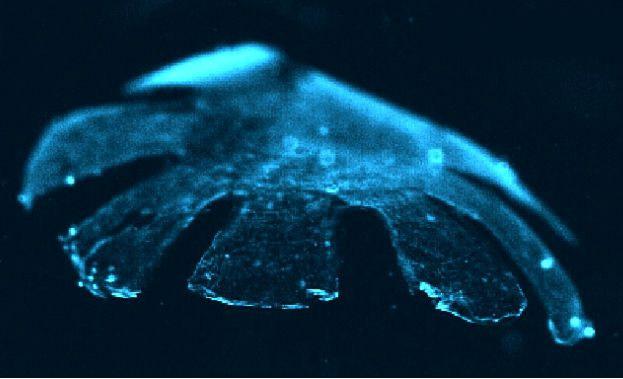

The jellyfish has 8 arms and is made up of a thin sheet of rat heart muscle cells and a thin silicone polymer. It can be "shocked to move" by applying current that causes it to propel itself in a conducting liquid.

The jellyfish propels itself through water by pumping almost similar to how a heart pumps blood in the body.

Next step, engineering organs

Scientists say that this study will help build artificial hearts that can replace damaged hearts in people. According to Kevin Kit Parker, PhD from Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, co-author of the study, the inspiration for building the artificial jellyfish came from the frustration that he had towards the present state for heart transplants. He then began looking at organisms that pump to survive.

"It occurred to me in 2007 that we might have failed to understand the fundamental laws of muscular pumps. I started looking at marine organisms that pump to survive. Then I saw a jellyfish at the New England Aquarium and I immediately noted both similarities and differences between how the jellyfish and the human heart pump," said Parker in a statement.

Previous research has shown that skin cells and stem cells can be turned into beating heart muscle cells. But, the present invention takes artificial organs to a whole new level by incorporating biological functions with an inanimate matter like silicone. Medusoid shows that a reverse-engineering a biological system is possible.

"A big goal of our study was to advance tissue engineering. In many ways, it is still a very qualitative art, with people trying to copy a tissue or organ just based on what they think is important or what they see as the major components—without necessarily understanding if those components are relevant to the desired function or without analyzing first how different materials could be used," said Janna Nawroth, a doctoral student in biology at Caltech and lead author of the study, in a statement.

Researchers say that will be putting a ‘brain’ in the jellyfish and give it more complex mechanisms like enabling it to respond to light or seeking out food or energy, according to a statement.

The study was published in Nature Biotechnology.

Published by Medicaldaily.com