'Bite Size' Documentary: Childhood Obesity And The Wall Kids, Parents, And Schools Face

Obese children live behind closed doors of pain and shame. They eat their emotions and encounter health issues their peers may never have to face in life. Bite Size, the newest childhood obesity documentary set to release March 24, produced by Eric Gallegos and directed by his best friend Corbin Billings, follows four kids struggling with obesity and the health consequences that accompany their size. Gallegos, who grew up with a type 2 diabetic father and a family history of obesity, wanted to pull back the curtain and let his audience see what it’s like for, not only the children that are suffering, but the parents, coaches, and school systems who battle to fight the epidemic.

Viewers first meet Davion Bland, a 12-year-old football player who has to routinely run off the field to get his blood sugar checked, trips during practice runs, and is unable to complete jumping jacks. But it isn’t his athletic hurdles that will upset viewers. Instead, the film shows the boy's realistic comprehension of his health.

“I have diabetes already, so I may not live that long,” Davion said. “I want to live as long as everybody else. But some people don’t live that long.”

A 12-year-old should never have to contend with the inevitability of his fate the way Davion does. But as viewers meet the other film’s stars, it becomes abhorrently apparent it’s a common trend in most obese children’s lives. Over the last 30 years, obesity rates have tripled among children and quadrupled among adolescents, and 13-year-old Emily Patrick is no exception to the rule.

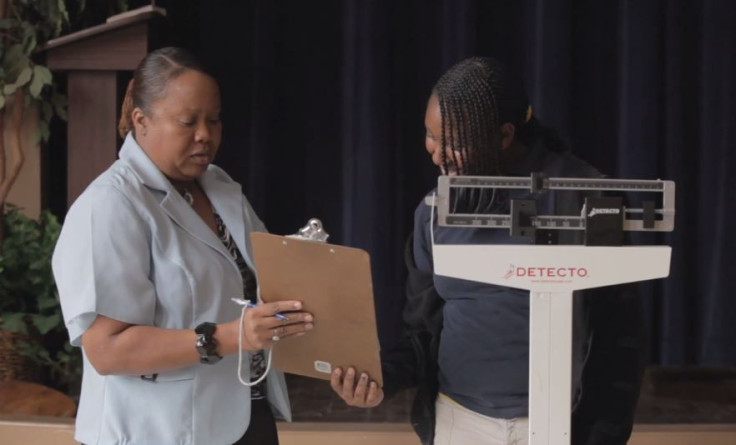

The Struggle For Health

“It takes effort to become 213 pounds at 12 years old,” Emily said. “The doctor told me I was going to die because of my weight. I just couldn’t ignore it anymore. I was looking for weight loss schools, and then I found MindStream. It was like the biggest loser for kids.”

Emily lived on a ranch with other kids, surrounded by personal trainers and beautiful rolling green hills. There, children are taught how to read food nutrition labels properly, get up, and run at 6:15 every morning, in addition to exercise programs throughout the day. They're also closely monitored and fed calculated meals, snacks, and drinks. Her trainer encouraged her to join a cross country or track team when she leaves camp, because, after all, the most difficult part of the process will be reentering a society that has taught instant gratification and overconsumption as the American way of life.

“Food addiction’s like a drug. Drugs are hard to get off of,” Emily said. “Drug addicts go to rehab to wean off drugs. We go to MindStream to wean off food addiction.”

It was Emily’s second trip to the camp, and after she left she promised herself she wouldn’t return. Bets were made on who would be back, and she was the winning horse. Her parents, who had spent all of their savings, had taken out loans, cashed out their IRAs and 401Ks, and retirement savings just to send Emily to the camp, are trying to follow her lead toward a healthier lifestyle for the entire family. Emily’s two older sisters are both obese, and although she hates to call them that, it’s a reality of her upbringing. Her father pours their liter bottles of diet soda down the sink and mom says goodbye to their long relationship with diet soda.

Next, viewers meet 11-year-old Moises “Moy” Gutierrez in Los Angeles, where his mother tries to change her family’s lifestyle and save her son from a full-blown type 2 diabetes diagnosis. However, viewers begin to realize just how responsible parents are for the health condition of their child.

Moy’s father tells the camera he’s a “fat little pig,” always eating, watching TV, and playing video games on the computer. It is not uncharacteristic for boys to indulge in games and action movies, but as his father jokingly chastises his unhealthy behavior, he commits the same fouls. After his father grabs at his chest until the ambulance comes from a stroke scare, he realizes “it’s not a joke anymore.”

A Cycle of Sickness

Children are being raised by parents who grow up with the same health problems, catching generations of families in a cyclical lineage. Obesity hits minorities at overwhelmingly high rates, nearly 50 percent of Hispanic blacks, followed by 42.5 percent Hispanics, and 32.6 percent whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Keanna Pollard is a 13-year-old stuck in the same unhealthy circuit her family was raised in. Her father takes no responsibility for what Keanna puts on her plate night after night at the dinner table, and says every individual has the right to choose, despite the environment that surrounds them.

“My best friend wants to lose weight and I do, too,” Keanna said. “But it’s hard to get out of that temptation of eating chips, cookies, drinking juices, eating chips and cookies back to back. We’ve been eating it like that for a long time.”

Keanna and her friends love to dance, says their school guidance counselor Lisa Ross. The girls talk and giggle about how they’re no longer allowed to dance like they used to, thanks to all of their “jelly” and “fatness.” Ross said the girls know they’re overweight, but they won't truly feel the effects until they become asthmatic or develop diabetes.

“I’m sick and tired of sticking my fingers every single day,” Ross says as she checks her insulin levels. “I’m sick of us suffering from preventable diseases. I don’t ever want them to suffer from diabetes. Who wants to suffer and lose their legs, their eye sight? No. I told them that we would be a group and need a name, that would describe the metamorphosis from where we are to where we need to be.”

That’s how the school’s weight loss program “Si Se Puede” was started, which translates to “we can do it” or “yes we can.” Keanna is enrolled in the program and signed a contract promising she wouldn’t touch another bag out of favorite chip snack. She laughs with her friend as she writes out her contract, and they agree they’re big, but they love being big.

This is a problem. Women in higher income brackets are less likely to be obese than low-income women, according to the CDC. Fast food, soda, chips, packets of doughnuts, and other highly processed foods are inexpensive and temporarily filling, which is why parents on a tight budget default to them to feed their families. But it’s only a short-term solution to a long-term health consequence that’s bound to catch children and their parents in the form of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, certain cancers, stroke, and hypertension.

“You’re getting your money’s worth when you eat healthy,” Ross said. “Poverty affects the choices that they make. We have to show them how much the state of Mississippi spends on diabetes health care, heart disease health care. We are the fattest part of the fattest state. We’re also the poorest part.”

Childhood obesity is a very complicated problem of misappropriated funds, poor patient compliance, and the manipulation of a billion-dollar food industry. Food is marketed to Americans unlike most countries, and we feed into the psychologically mouthwatering sign colors to the fad diet lures. The 17 percent of obese children and adolescents of this country are likely to group up to become obese adults, adding to another generation of life-threatening health consequences.