Electric Brain Stimulation Helps Stroke Patients Improve Motor Skills During Rehabilitation

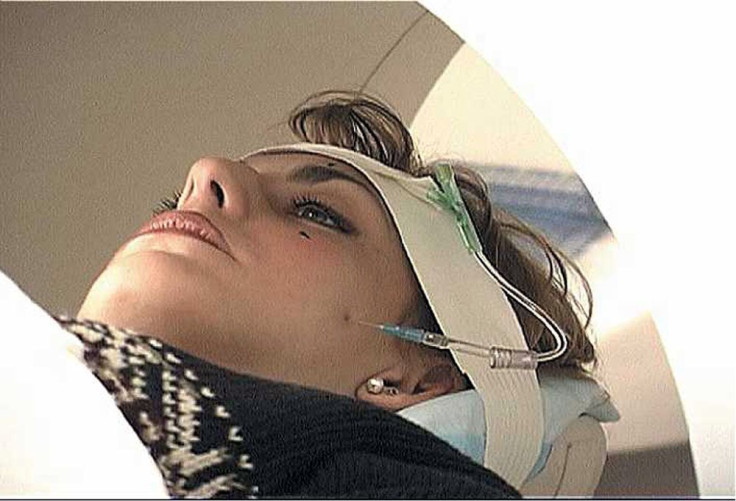

Electrified, our brains work better. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a painless treatment that uses electrical currents to stimulate parts of the brain. A new study from Oxford University researchers investigates this method of jumpstarting the mind. Their results suggest the use of tDCS effectively supports patients during rehabilitation after stroke.

Specifically, participants who received electrical brain stimulation in addition to rehabilitation therapy following a stroke showed more improved motor skills than participants treated only with the usual rehabilitation. Improvements were lasting, as well, said the researchers.

Transcranial direct current stimulation is not a new idea, say the authors of a scientific article published in 2012. The physician of Roman Emperor Claudius described placing a live torpedo fish on one’s scalp to deliver a strong electric current for headache relief. Ancient medical researchers recount other assorted attempts to harness electricity for therapy, while in the 11th Century, a Muslim physician suggested using a live electric catfish to treat epilepsy.

Once the electric battery was introduced in the 18th Century, researchers began experimenting more and more with electrical stimulation and discovered a variety of different effects it had on human physiology. In the past two centuries, psychiatrists introduced the use of electric currents as a treatment for brain disorders, while scientists experimented with their use to alleviate musculoskeletal disorders and peripheral pain. Over the past hundred years, the basic technique of tDCS has been refined. The most recent scientific evidence verifies that stimulating the brain in this way can induce changes in neuropsychological, psychophysiological, and motor activity.

For the current study, Professor Heidi Johansen-Berg, Dr. Charlotte Stagg and their colleagues used a variant of electric stimulation known as ipsilesional anodal tDCS. Here, a positive (or anodal) current is applied, via a cathode placed on the skull, to the side of the brain where damage has occurred. Previous research suggests similar types of stimulation have improved the learning of motor skills in healthy people.

The Oxford researchers theorized these same effects might reinforce the rehabilitation training offered to stroke patients who are re-learning how to use their bodies.

Placebo tDCS?

The study evaluated 24 people whose hand and arm function had been affected by a stroke. Split into two groups, one group received nine days of motor training plus tDCS; the other group also received nine days of motor training but they were fitted with fake electrodes unable to deliver tDCS. “Placebo” tDCS is necessary to rule out any possible psychological boost from receiving extra treatment. Before, during, and up to three months after the training, the researchers measured participants’ motor skills to see how much they had improved.

Three months after training, the group that had received tDCS showed greater improvements in all areas measured compared to those in the control group. The tDCS patients displayed better use of their hands and arms for movements such as lifting, reaching, and grasping objects, the researchers noted.

Brain scans also indicated those in the tDCS group had more activity in the brain areas relevant to motor skills than the others.

“These findings suggest that brain stimulation could be added to rehabilitative training to improve outcomes in stroke patients,” concluded the researchers.

Source: Allman C, Amadi U, Winkler AM, et al. Ipsilesional anodal tDCS enhances the functional benefits of rehabilitation in patients after stroke. Science Translational Medicine. 2016.