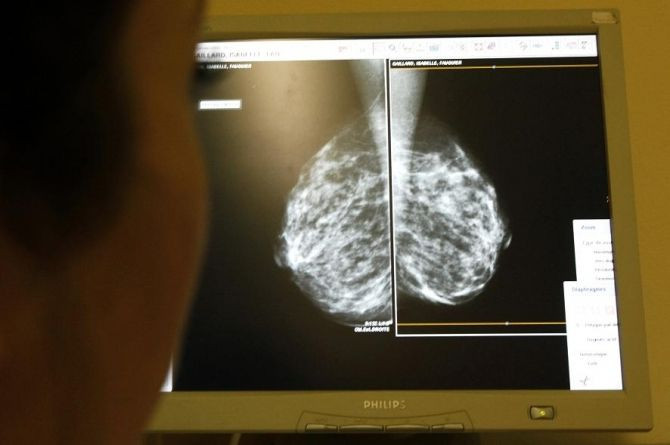

Breast Cancer DNA Analysis Divides Disease Into 4 Treatable Types

For years, breast cancer has been considered a single disease, but recent findings show a number of genetically distinct variations that may actually divide the disease into four differently treatable types.

The latest comprehensive analysis of the genetics and breast cancer, published in the journal Nature, may lead to more effective treatments of the disease with some drugs already in use like ones against ovarian cancer.

Not only did the research suggest that there are four distinct types of breast cancer which show hallmark genetic changes, they also reveal that certain breast cancers, like basal-like breast tumors, one of the deadliest subtypes of breast cancer, are genetically more similar to ovarian cancer than other breast cancer subtypes.

The latest findings add to the growing evidence suggesting that cancer tumors should be categorized and treated based on the tumor DNA rather than be based on where cancer arises in the body. Researchers hope that the research in the biology of tumors can reveal cancer's genetic weaknesses for more effective drug targeting.

"With this study, we're one giant step closer to understanding the genetic origins of the four major subtypes of breast cancer," lead author Dr. Matthew Ellis of the Washington University School of Medicine said in a statement. "Now we can investigate which drugs work best for patients based on the genetic profiles of their tumors," he said.

Scientists had analyzed the DNA of tumors from 825 breast cancer patients to look for abnormalities and found that breast cancers appeared to fall into four main classes with unique genetic and molecular signatures within each of the subtypes: luminol A, luminal B, HER2 and basal-like.

Researchers found that one class of breast cancer, basal-like breast tumors, showed remarkable similarities to ovarian cancers, suggesting that both diseases may be driven by similar biological developments.

"For basal-like breast tumors, it's clear they are genetically more similar to ovarian tumors than to other breast cancers," Ellis said. "Whether they can be treated the same way is an intriguing possibility that needs to be explored."

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, and a large proportion of cases are sporadic as opposed to genetic, meaning there is not a family history of breast cancer. Men can also develop breast cancer, but that only accounts for less than 1 percent of all breast cancer cases.

The American Cancer Society estimates there will be 226,870 women in the U.S. will develop invasive breast cancer and about 39,510 women will die from breast cancer in 2012, and the statistics from the World Health Organization shows that there are approximately 1.3 million new cases of breast cancer and 450,000 deaths worldwide annually.

"This research is geared toward finding ways to individualize cancer treatment," said Dr. Stephanie Bernik, chief of surgical oncology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, according to HealthDay. "When treating breast cancer, we offer specific therapies that have been tested on large populations of cancer patients. However, one treatment is not necessarily good for all."

Bernik said that the latest research helps "move us to the point where we will look at a tumor's genetic makeup and tailor a specific treatment that will attack the tumor cells based on the tumor's genetic fingerprint."

Dr. Donna-Marie Manasseh, director of breast surgery at the Maimonides Breast Cancer Center in New York City said the new study "provides hope to many woman and clinicians who battle breast cancer every day," according to HealthDay.

"Breast cancer is not just one disease and, therefore, requires not just one type of therapy but rather different disease types that require specific therapies targeted for each type," she added. "Targeted therapies allow for more effective treatment of tumors, while minimizing the treatment of tumors with less effective therapies and their subsequent side effects."

Published by Medicaldaily.com