A Brief History Of Bathing: The Importance Of Hygiene, From Ancient Rome’s Sophisticated Showers To The Modern Day

One might imagine that before the modern age, humans were dirty and barbaric, not showering for days, weeks, or even months at a time. But of course history is never so simple, and plenty of ancient cultures had their own sophisticated bathing rituals — whether for hygienic, religious, therapeutic, or even social purposes.

Amazingly enough, the ancient Greeks were the first to develop showers, where water actually flowed through lead pipes over people’s heads. The Romans expanded on this pipe system, creating expansive aqueducts that supplied indoor plumbing and bathhouses with water. Public bathhouses were essentially the ancient form of spas, offering massages, exercise, and entertainment, while also being the meeting place to socialize.

Though humans throughout history didn’t have all the scientific evidence showing the medical importance of hygiene like we do today, cleanliness was still often associated with power, spirituality, and even beauty. Strangely enough, although we view bathing as a private matter today, it was a shared ritual for thousands of years — a way to build community and human connection.

ANCIENT

3000-2001 B.C. In prehistoric times, the sea and rivers served as the most raw and original — and perhaps the purest — form of a bath. Waterfalls were showers. But as communities and societies formed in the ancient world, public baths became the main form of bathing, simply because they were a convenient way to wash when people didn’t have access to private bathing facilities. Archaeologists list the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro as one of the earliest public baths in history. Located in Sindh, Pakistan, the bath dates back to the ancient Indus Valley Civilization — one of the three oldest human civilizations, next to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Two stairwells led into the bath, which measured nearly 40 feet by 22 feet.

1500 B.C. Ancient Egyptians placed high importance on the rituals of washing, bathing, and applying cosmetics, as it was believed that the cleaner and well-oiled the person was, the closer they were to the gods. Hygiene, makeup, and clothing was also considered essential when burying the dead, as it would assist them during the Judgment of the Dead, their gateway to the afterlife. Egyptians used a scented paste consisting of ash and clay for soap, and the Ebers Papyrus, a source for medical knowledge, instructed people to mix animal and vegetable oils with alkaline salts for washing and treating skin diseases. Many washed themselves several times a day, including after rising and before and after meals, though “washing” typically meant rinsing their hands, faces, or feet in water basins with the aforementioned pastes. Plucking and shaving all of their hair (instead choosing to wear wigs and draw on eyebrows) was also a popular trend of beauty among both men and women.

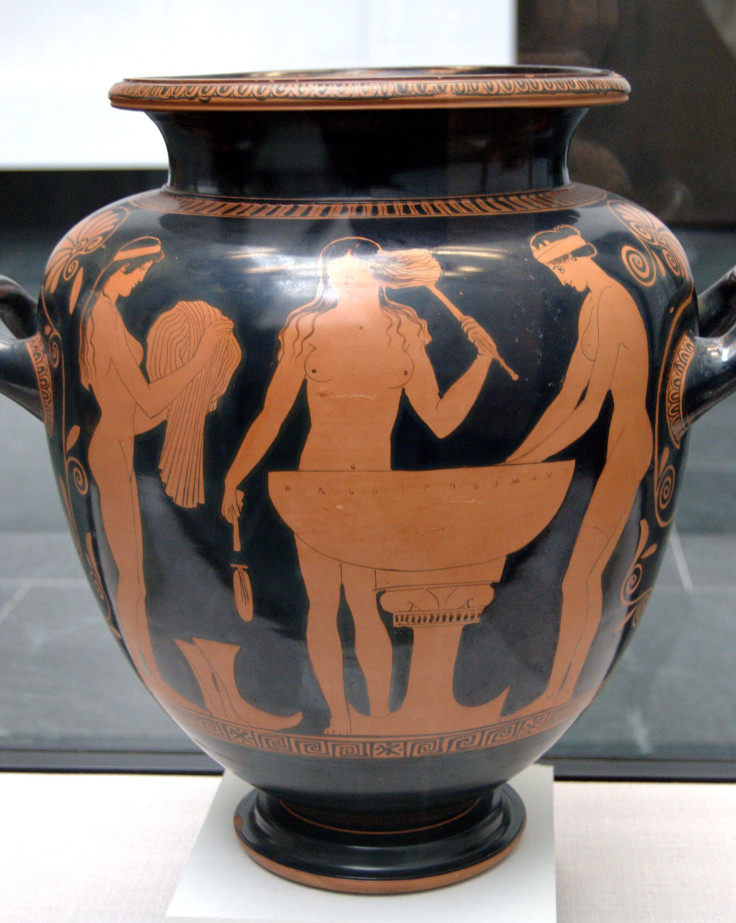

500-300 B.C. “Showers” in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia involved rich people having private rooms in which servants poured cold water out of jugs over them, but the ancient Greeks were really the first to pioneer what we now consider the modern shower. The gymnasiums of classical Greece were places for men to train in sports and participate in public games. Because the ancient Greek term “gymnós” actually means “naked,” athletes competed there in the nude as a way to appreciate the male form. Gymnasiums had to provide athletes with a place to bathe after their exercises, so showers and indoor plumbing appeared in gymnasiums first.

The Roman era. The city of Bath, known as Aquae Sulis during ancient Roman times and located in what is now England, was perhaps a quintessential example of bathing culture in Rome during its heydey. Notorious for being a city of bathing, Bath contained an array of amazing public baths with hydrothermal springs and sophisticated water systems.

In many ways, Roman bathhouses were the center of the town or city — hubs for exercise, relaxation, and socializing. They were highly complex buildings; often the first thing to be built in a new town, they contained a series of rooms with different temperatures ranging from cold to hot. They also featured special areas for changing clothes, restrooms, massages, exercise, and even areas to eat and drink wine. Heating was provided in the bathhouse through hypocausts, hollow spaces underneath the floors through which hot air traveled from furnaces, and water was supplied through pipes, drains, and sewers.

“The Roman bath house was one of the foremost buildings in a Roman town,” according to Historic England. “Private bath houses in towns were rare, and usually the preserve of the rich. The majority of the populace used public bath houses,” which consisted of “a series of rooms of graded temperatures with associated plunge baths.”

Men who attended these baths would first exercise to work up a sweat, then scrape off their perspiration with a little tool called a strigil. Afterward, they’d go from a tepid bath to a hot one, followed by a plunge into a cold bath. The bathhouses even provided medical treatment and haircuts as barbers back then could also pull teeth and do minor surgeries.

MEDIEVAL

476 A.D. When the Roman empire collapsed and the Dark Ages rolled in, the Roman aqueducts and indoor plumbing fell into disuse and disrepair. As a result, a lot of showers, public bathhouses, and private bathing facilities disappeared, ushering in a new era of uncleanliness throughout Europe.

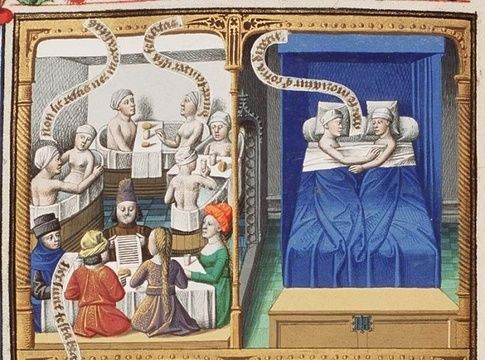

700s A.D. But despite the popular belief that the Medieval era were a cesspool of absolute filth, public bathhouses in the Western world still existed — some in very strange ways. Public bathhouses, despite some disapproval from the Catholic Church, carried on as centers of socialization and relaxation. People would even have dinner parties in baths, with a plank placed over the top of the bath as a table for food, and a musician entertaining them nearby. Some bathhouses gained a reputation for being similar to brothels, where people could engage in sexual acts.

Einhard, a scholar and scribe of Charlemagne, described the King of the Franks’ bath parties: “[He] would invite not only his sons to bathe with him, but his nobles and friends as well, and occasionally even a crowd of attendants and bodyguards, so that sometimes a hundred men or more would be in the water together.”

710-1300s A.D. In Asia, the bathing culture can be traced back to Buddhist temples in India, where priests bathed for religious reasons. This bathing culture spread to China and then to Japan during the Nara period, practiced mainly by Buddhist priests. These steam baths were called yūya, which meant “hot water shop,” but they began to expand when sick people started flocking to the water as a form of healing.

Bathing as religious ritual had existed for thousands of years, primarily among Jews, Muslims, and Buddhists. The need to remove both bodily and spiritual impurities predated the germ theory of disease by thousands of years, and scientists aren’t sure what motivated people to associate holiness with cleansing.

1340s-1350s . The Bubonic Plague changed the way a large chunk of Europeans viewed bathhouses. As there was yet no scientific or medical understanding of germs, people worried that open pores could allow illness to enter their bodies, and believed that dirt all over their skin would block disease. In addition, the Church’s moral viewpoints began painting public bathhouses as dens of sin where men and women could mingle in the nude and have sex. These two things deterred more and more people from bathing in communal places.

Of course, the level at which medieval people continued to bathe depended on their level of wealth, status, and personal preferences. It’s said that the Benedictine monks of Westminster Abbey bathed only four times a year — once on Easter, once at the end of June, once at the end of September, and once on Christmas — according to monastic rules. But others bathed far more frequently, particularly kings and the wealthy. In 1351, King Edward III purchased hot and cold taps of water to be provided for his personal bathtub at Westminster Palace.

In the Western world, the bubonic plague had scared people from being in water, but Eastern countries and religions still maintained unbroken standards for hygiene and cleanliness.

MODERN

18th century. The notion that bathing and hygiene could serve medical purposes and lead to better health didn’t arrive until the 18th and 19th centuries; in fact, doctors didn’t even wash their hands before surgery until they accepted Ignaz Semmelweis’ findings on germs in the late 1800s. In the 1700s, the idea that water could be used for therapeutic purposes — termed hydrotherapy — gained some popularity, and several books were written on the cold water cure.

1767. The first modern mechanical shower was invented by William Feetham in England. The contraption involved a pump that pushed water into a vessel that hung above a person’s head; the person could then pull a chain to release water from the vessel.

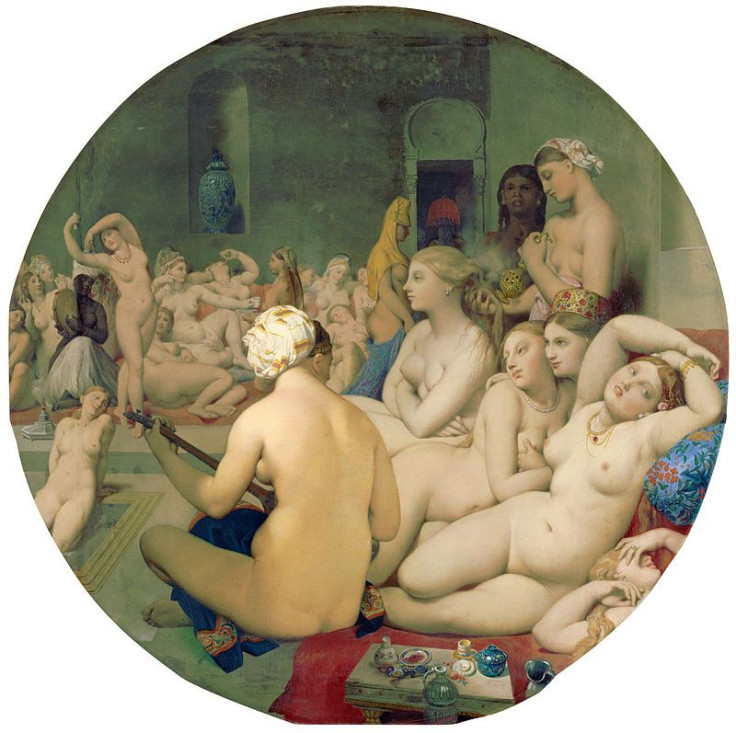

1829. After a hiatus, public baths began to reopen in the 1800s. The first modern public baths were opened in Liverpool, England, in 1829. And a renewed interest in ancient Roman and Turkish baths, such as those used by the Ottoman Empire, spurred the Western world to open its doors to cleaner versions of these public bathhouses.

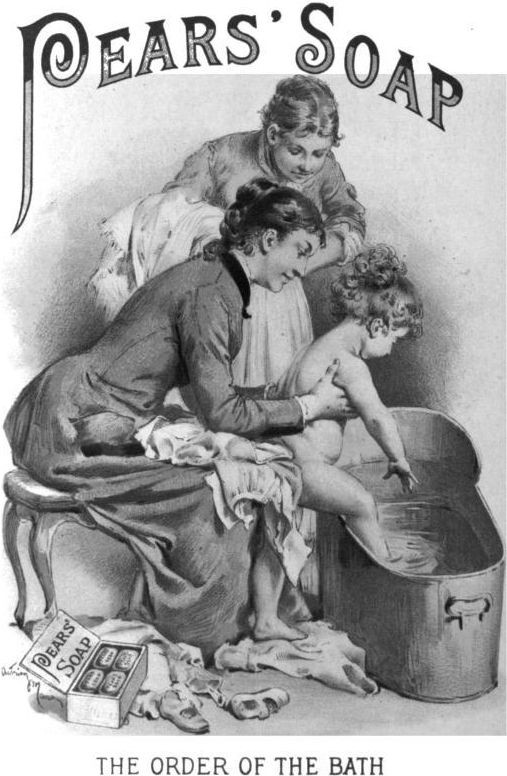

1861. By now, the idea that a lot of diseases could be prevented by sanitation and good hygiene had begun to take hold. In 1861, the U.S. Sanitary Commission was created as a relief agency to help wounded soldiers during the Civil War, and it pioneered a new era of sanitation after discovering that by simply washing patients, their clothes, and the walls of their rooms, doctors could save many more people from disease. Perhaps it was in this era that Americans began their obsession with cleanliness, daily washing, the best shampoos, perfumes, and soaps — and even white teeth.

“ Before the war, Americans had been just as dirty as Europeans, and they came out of the war thinking cleanliness is democratic… It’s progressive. It’s forward-looking. It has wonderful results,” Katherine Ashenburg, author of The Dirt on Clean: An Unsanitized History , told Salon . “They quickly thought this is yet another way in which life in the New World is so much better than life in the Old World. The invention of modern sophisticated advertising, which began in America at the end of the 19th century, achieved an enormous success, often by advertising things like toilet soap and deodorant.”

Early 1900s. A typical Saturday night in the early 1900s involved American family members fetching and carrying loads of water into the kitchen, heating it, then filling a bath with it. Usually, the father of the family bathed first, followed by the mother, then the children, with the youngest last. Saturday night bathing rituals were a way to prepare for the laborer’s Sunday of rest.

Today, the average working American showers daily, sometimes twice a day — typically after waking or before going to sleep. Showering or taking baths are now private affairs, but it’s not hard to see that bathing in general can have health benefits beyond removing dirt and germs from our skin’s surface. Taking baths in particular can reduce stress, improve cold symptoms through the steam, relax muscles, and aid in better sleep. Mixing that with exercise and a good intellectual conversation can only make it better — the ancient Romans and Ottomans were certainly onto something when bathhouses were centers of cultural and social gatherings.