Cancer Cells Devise Way To Survive Chemotherapy

Cannibalism among cancer cells is one of the major causes of chemotherapy resistance.

Resistance, which occurs when cancers that have been responding to chemo suddenly begin to grow, is normally associated with the massive production by cancer cells of p-glycoprotein pumps, gene amplification and the repair of DNA breaks caused by some anti-cancer drugs such as doxorubicin, among others.

But cannibalism does exist and while uncommon, adds to the burden of curing or mitigating cancer via chemotherapy.

A new study from Tulane University suggests some cancer cells survive chemotherapy by devouring their neighboring tumor cells in a ruthless bid to withstand chemotherapy. This cellular cannibalism is thought to give predatory cancer cells the energy they need to stay alive. It also allows them to begin tumor relapse after the chemotherapy treatment is completed.

Chemotherapy drugs, among them doxorubicin, kill cancer cells by damaging their DNA. Unfortunately, cancer cells that survive the initial treatment give rise to relapsed tumors.

This is an especially thorny problem in breast cancers that retain a normal copy of a gene called TP53. This protein acts as a tumor suppressor. This means it regulates cell division by keeping cells from growing and proliferating too fast or in an uncontrolled way.

Some cancer cells generally stop proliferating and enter a dormant but metabolically active state known as senescence, instead of dying due to chemotherapy-induced DNA damage. Senescent cancer cells also produce large amounts of inflammatory molecules and other factors that can promote the tumor’s regrowth.

Chemotherapy-treated breast cancer patients with normal TP53 genes become prone to relapse and have poor survival rates.

“Understanding the properties of these senescent cancer cells that allow their survival after chemotherapy treatment is extremely important,” Crystal A. Tonnessen-Murray, a postdoctoral research fellow at James G. Jackson’s laboratory at the Tulane University School of Medicine, who led the research team, said.

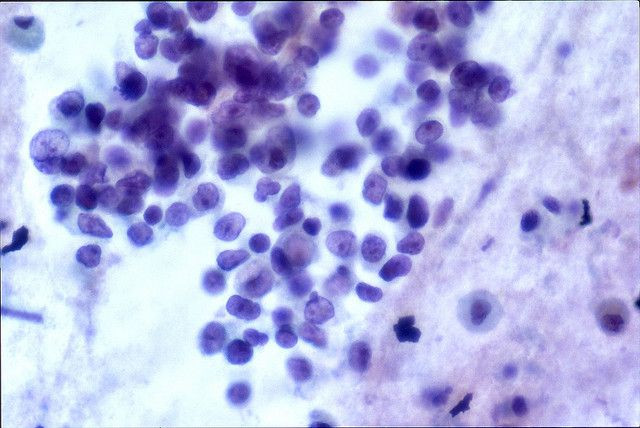

Her team also discovered that senescent breast cancer cells frequently engulf neighboring cancer cells following exposure to doxorubicin or other chemotherapy drugs. Researchers observed this surprising behavior in cancer cells grown in the lab and also in tumors growing in mice.

They also found that lung and bone cancer cells are also capable of engulfing their neighbors after becoming senescent.

Tonnessen-Murray and her colleagues found that senescent cancer cells activate a group of genes, which are normally active in white blood cells, that engulf invading microbes or cellular debris. They saw that after “eating” their neighboring cancer cells, senescent cancer cells digested them by delivering them to lysosomes, which are acidic cellular structures highly active in senescent cells.

But the most important finding was that this process helps senescent cancer cells stay alive. Senescent cancer cells that engulfed neighboring cells survived in culture for longer than senescent cancer cells that didn’t.