Cancer: In Lifestyle vs. ‘Bad Luck’ Debate, DNA Errors Aren’t The Biggest Culprits

Errors in the DNA of human stem cells occur at a constant rate even in organs that have different rates of cancer incidence, researchers found. The study debunks the belief that the difference in cancer risk in different organs can be attributed to the number of errors during stem cell processes.

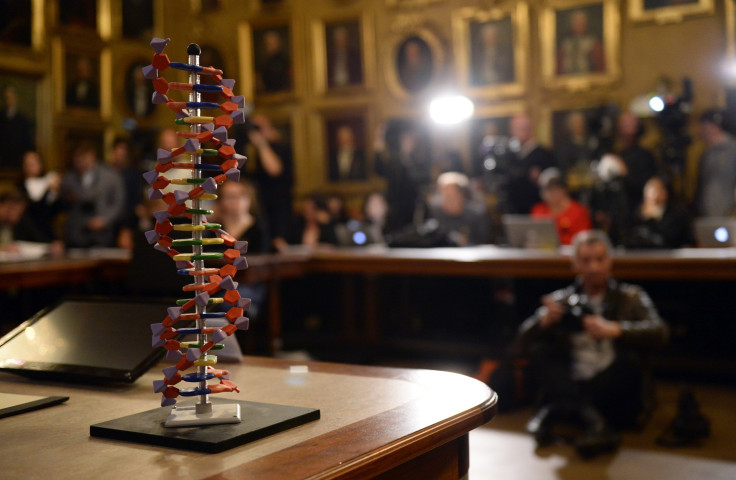

Our cells are constantly bombarded by external forces that damage the DNA whether it is cigarette smoke or the sun. As this damage accumulates over time, it can lead to cancer. While we can minimize our exposure to these external forces, sometimes, our own cells work against the body. Errors in cell division and other processes can result in ‘random mutations’ or ‘bad luck’ DNA mutations.

Previous research suggested that these ‘bad luck’ DNA errors accumulate over time and increase the risk for most cancers. This would indicate that organs that show faster rates of stem cell division would accumulate more errors and therefore the risk of developing cancer in these organs is far greater.

Researchers from the UMC Utrecht in the Netherlands analyzed stem cells left over from tissue samples collected during routine biopsies. These cells were gathered from the colon, liver and small intestines which have starkly different rates of cancer incidence. The cells belonged to patients from a varied age group ranging from 3 years old to 87 years old.

The study published Monday in the journal Nature is the first to directly measure DNA errors in human stem cells from different organs and from people belonging to different age groups.

“We were surprised to find roughly the same mutation rate in stem cells from organs with different cancer incidence,” Ruben van Boxtel, lead researcher of the team, said in a statement. “This suggests that simply the gradual accumulation of more and more ‘bad luck’ DNA errors over time cannot explain the difference we see in cancer incidence -- at least for some cancers.”

The team found that the DNA error accumulation in the different organs did not vary but remained at a stable 40 errors a year. This rate stayed stable irrespective of the organ or the age of the patient. There were, however, differences in the types of DNA errors between tissues, which could partly explain the increase cancer risk in some organs like the bowel.

“So it seems ‘bad luck’ is definitely part of the story,” van Boxtel said. “But we need much more evidence to find out how, and to what extent. This is what we want to focus on next.”

“Lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet can account for part of the difference in cancer incidence, but researchers don’t yet fully know why some types of cancer are more common,” Lara Bennett, Science Communication Manager at Worldwide Cancer Research which funded this research, said in the statement. “This new research by Dr van Boxtel and his group is important because it provides actual measured data on the rate of DNA error accumulation in human stem cells for the first time, and shows that perhaps not as much cancer risk is down to this type of ‘bad luck’ process as has recently been suggested.”