CDC Issues Guidelines For Pregnant Women During Zika Outbreak

CHICAGO (Reuters) - The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on Tuesday issued guidelines for doctors caring for pregnant women who might have been exposed to Zika virus, a mosquito-borne infection that can cause brain damage in a developing fetus.

The new guidelines, first reported by Reuters, lay out recommendations for doctors whose pregnant patients have traveled to areas with Zika virus transmission.

They follow a travel advisory issued by the CDC on Friday warning pregnant women to avoid travel to 14 countries and territories in the Caribbean and Latin America affected by the virus.

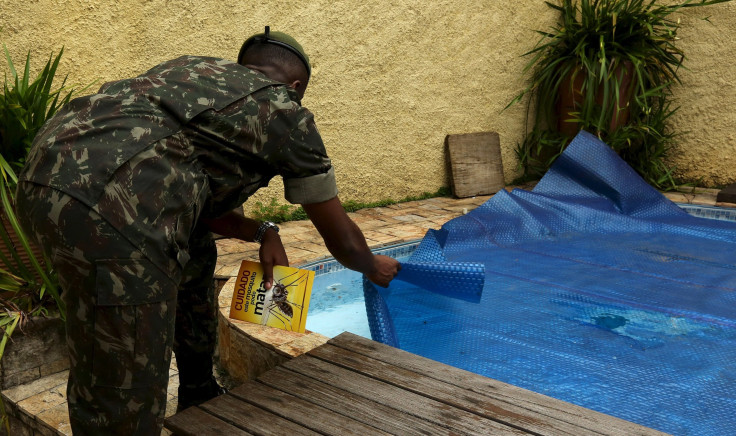

In Brazil, Zika has been linked to a rising number of cases of microcephaly, a condition associated with small head size and brain damage. Tourism officials in that country have tried to play down the risks as the country gears up for Carnivale and the 2016 Olympics, the first in South America.

On Saturday, health officials confirmed the birth of the first baby born with microcephaly in the United States attributed to the virus. The child was born in Hawaii to a mother who had become ill with Zika virus while living in Brazil last May.

There is no vaccine or treatment for Zika, which causes mild fever and rash. An estimated 80 percent of people infected with the virus have no symptoms at all, making it difficult for pregnant women to know whether they have been infected.

In its latest to doctors, the CDC urges providers to ask pregnant women about their travel history. Women who have traveled to regions in which Zika is active and who report symptoms during or within two weeks of travel should be offered a test for Zika virus infection.

Those who test positive should be offered an ultrasound to check the fetus's head size or check for calcium deposits in the brain, two indicators of microcephaly. These women should also be offered a test of their amniotic fluid called amniocentesis to confirm the presence of Zika virus.

Pregnant women who traveled in areas where Zika is active but have no clinical symptoms should also be offered an ultrasound, and women whose fetus shows signs of microcephaly should also be offered amniocentesis. Those with no positive findings should be offered frequent ultrasounds to check for changes in the baby's head size.

Pregnant women with laboratory-confirmed evidence of Zika infection should be offered ultrasounds every three to four weeks to monitor fetal anatomy or growth. The CDC recommends that these women be referred to a maternal-fetal medicine or infectious disease expert with expertise in managing high-risk pregnancies.

EARLY DETECTION

While there is no treatment for microcephaly, early detection might offer some women the option of terminating their pregnancies or to have specialists on hand at delivery, said Dr. Laura Riley, president of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, who has been working with the CDC on the guidelines.

Riley, an expert in high-risk pregnancies who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said she is writing practice guidelines for the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, which will be released in partnership with The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Riley said the guidelines could be released as early as Wednesday.

"We're going to be recommending people get an ultrasound. If that is normal, great, but it needs to be followed up," Riley said.

Since the CDC issued its travel advisory, Riley said she has had several calls to her practice from families asking whether they should cancel their travel plans.

She also has had calls from worried patients who have already traveled to countries with Zika outbreaks.

The guidelines will give doctors like her some answers for those patients. Even so, there are many unknowns, Riley said.

For example, it is not clear how accurate a test of amniotic fluid would be in detecting Zika infections, especially those that might have occurred earlier during the pregnancy. In addition, even though a child might show signs suggesting a smaller head size on an ultrasound, that does not give doctors a clear picture of whether the child will have extensive brain damage, Riley said.

And testing could be an issue. Currently, there are no commercially available diagnostic tests for Zika infection. Tests to confirm Zika will require advanced laboratory capabilities beyond what is available in most local hospitals.

According to the guidelines, testing for Zika virus will be performed by the CDC and several state health departments. Doctors are urged to contact their state or local health department to arrange for testing or to interpret results.

Despite the advice, experts admit there is still much about Zika infections that is unknown.

"People are making educated guesses," said Paul Roepe, co-director of the Center for Infectious Disease at Georgetown University Medical Center.

For example, he said it is not clear how common Zika infection is in pregnant women, or when during a pregnancy a woman is most at risk of transmitting the virus to her fetus.

"Does it happen in first few weeks for the first trimester?I'm not sure anybody really knows," he said.

(Reporting by Julie Steenhuysen; Editing by G Crosse and Jonathan Oatis)