Celebrity Endorsements: Why They May Not Be As Successful As Advertisers Believe

Whenever you find yourself in a waiting room or a salon, you probably end up thumbing through one or another of the magazines lying around the place. So what happens when you happen to see two separate advertisements with the same celebrity endorsing different products — do you remember one product and not the other? An hour later, have you forgotten both?

Coming upon two ads featuring the same celebrity, you will in all likelihood forget a product if it is only moderately associated with a celebrity’s fame, a team of marketing researchers discovered. If, however, the product is either a good fit — or a wildly bad one — you will remember the advertised information. The research appears in Psychology and Marketing.

The cult of celebrity may represent the worst in human nature or simply be an example of the need for occasional amusement. After all, are most of the celebrities mentioned in the titles of articles glimpsed before we open our email relevant or admirable to us? In many cases, most of us would answer "no." Yet, these celebrities are paid to endorse products simply because they have captured, if not our own attention, then that of the media.

What, then, is the true effectiveness of a celebrity endorsement? Dr. Katie Kelting, assistant professor of marketing at University of Arkansas, and Dr. Dan Hamilton Rice, marketing professor at Louisiana State University, enlisted the help of 235 undergraduate students to explore this issue.

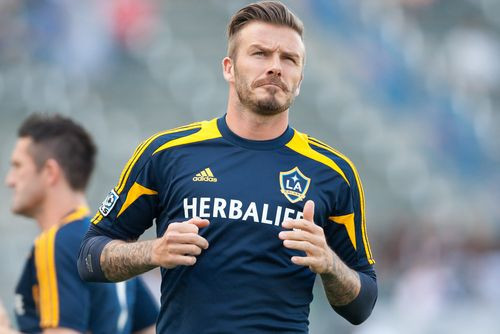

For their experiment, the researchers presented eight print advertisements to each of the study participants. Of these ads, six were filler material, identical for all the participants, while the remaining two ads ads — one “interfering” ad and one “target” ad — were key to the experiment. While the so-called filler ads featured fictitious brands of bourbon, cologne, dog food, gum, a sports utility vehicle and a watch, the interfering and target remaining ads were both endorsed by the same celebrity, in this case professional soccer player David Beckham. In the interfering ad, three separate groups of students saw Beckham endorsing either a sports drink, an MP3 player, or a baseball bat, while in the target ad, he was always seen endorsing a camera.

How likely were participants to remember the target ad? Depending on which interfering ad a participant saw, their recall for the camera ad was affected. For instance, when later asked which products Beckham advertised, the students were less likely to remember the camera when also shown the sports drink — a high match for Beckham’s celebrity — and the baseball bat — a low match. However, when participants were shown the MP3 player ad, which had only a moderate connection to Beckham’s celebrity, they were more likely to remember the camera ad.

Kelting said this experiment demonstrates how different brands in a celebrity’s “endorsement portfolio” compete with each other when the celebrity is used by consumers as a memory retrieval cue. Brands that have either a high or low match with a celebrity’s reason for being famous, win the mental retrieval competition and end up blocking a consumers’ ability to remember information in ads that are only a moderate match with a celebrity.

Previous studies have focused on consumer attitudes toward a celebrity to gauge possible effectiveness; the most likeable celebrities, it has been assumed, win the most attention from consumers no matter what product they endorse. But, as Kelting and Rice prove here, attitude and certain memories do not always predict effectiveness. For example, the Energizer bunny initially backfired because, even though the ad was popular and memorable, consumers could not remember which brand the campaign advertised. Energizer eventually solved the problem by placing an image of the bunny on its packaging.

“Our findings demonstrate that marketers should think hard, or at least be strategic, about using celebrities to sell their products,” Kelting said in a press release. “They shouldn’t expect consumer memory to be accurate, especially when the famous face endorses other brands. If consumers like a celebrity ad featuring LeBron James when they see it but cannot remember which brand of insurance he endorsed when they are later in the market for car insurance, then what was the point of hiring LeBron James in the first place?”

Source: Kelting K, Rice DH. Should We Hire David Beckham to Endorse our Brand? Contextual Interference and Consumer Memory for Brands in a Celebrity's Endorsement Portfolio. Psychology and Marketing. 2014.