Cervical Health Awareness Month: Everything You Need To Know About Preventing And Treating Cervical Cancer

Thirty years ago, cervical cancer was one of the most common causes of cancer death among American women, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). Today, however, the ACS finds the cervical cancer death rate has plummeted by more than 50 percent — it’s now considered one of the most preventable types of cancer.

The disease is preventable when women adhere to cervical cancer guidelines. Like with breast cancer, however, this can be easier said than done. Guidelines are under constant evaluation in order to ensure they reflect the most recent research and data on effective detection and treatment methods. Yet, perhaps unintentionally, the new versions often create gray areas wherein there is information opposite or contradictory to what women have been led to believe and practice.

Enter Cervical Health Awareness Month. According to the National Cervical Cancer Coalition (NCCC), the United States Congress designated January the month to "highlight issues related to cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV) disease, and the importance of early detection."

So, we turned to Fred Wyand, director of communications for the American Sexual Health Association/NCCC, to do just that.

Preventable and Curable

There are five main types of gynecological cancer: cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Of these five, cervical is the easiest to prevent with regular screening tests and follow-up; it’s also "highly curable when found and treated early."

All women have a certain risk for cervical cancer, but it occurs most often in midlife, between the ages 35 and 55. The CDC reports each year, an estimated 12,000 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer in the U.S. Cervical cancer rarely affects women under age 20, and approximately 20 percent of diagnoses are made in women aged 65 and older, according to Wyand.

There are, however, some racial and ethnic disparities. Wyand found the highest rates of cervical cancer are found in Hispanic women, followed by African American, white, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Asian/Pacific Islander women. "In fact, the cervical cancer incidence rate is 64 [percent] higher among Hispanics and 34 [percent] higher among African Americans than among whites," he said.

In terms of death rates, black women are more likely to die from cervical cancer than any other racial or ethnic group, followed by Hispanics, white, Asian Pacific/Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native, Wyand added. Black women are reportedly twice as likely to die from this cancer than white women.

What’s interesting about these death rates are that black women also have the highest rates of recent pap testing to screen for the disease, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). What could account for the paradox? KFF suggest it could be this population of women "has limited access to treatment and diagnosis at later stages of disease progression, as well as cost, lack of physician referral, and cultural barriers."

Cervical Cancer And HPV

HPV causes 99 percent of cervical cancer cases, Wyand said. Women have a higher risk of contracting the virus, which is passed from one person to another during sex, if they start having sex at an early age and/or have sex with several partners — or someone who’s had several partners. While the CDC reports at least half of sexually active women will have HPV at some point in their lives, few women will get cervical cancer.

The virus strains that lead to cancer are considered high-risk HPV types, Wyand explained; overall, there are over 100 different types of HPV. More than 70 percent of cases are attributable to high-risk types known as HPV-16 and HPV-18.

"Most forms of HPV clear up on their own, without causing any health problems," Wyand said. "In fact, it is estimated that 90 percent of HPV infections become undetectable within approximately two years (more on this later)."

In addition to HPV, the ACS lists smoking, young age at first pregnancy, family history, diet, and oral contraceptives as possible risk factors for cervical cancer, while other studies have suggested untreated chlamydia and persistent oncogenic HPV infection can also increase risk. Not smoking makes it easier for the immune system to respond to infection, Wyand said. Moreover, a 2008 study found a diet rich in fiber, vitamins A, C, E, and otherwise fruits and vegetables was associated with 40 to 60 percent reduction in cervical cancer risk.

"It’s true that studies indicate an increased risk among women who take oral contraceptives for five or more years (the risk declines once OC use is stopped)," Wyand said. "Keep in mind that the risk of cervical cancer is still very small, and that regular, appropriate screening is the key to preventing the disease. Also, pregnancy is hardly a benign condition! So women should talk to their health care providers to weigh the slightly increased risk of cervical cancer while keeping in mind what are their best options for contraception."

Get Tested

Precancerous cervical cell changes and early stage cervical cancer do not cause symptoms, Wyand said, but more advanced cases might. Possible symptoms of more advanced disease may include abnormal or irregular vaginal bleeding, pain during sex and/or pain unrelated to menstruation, vaginal discharge, increased urinary frequency, and/or pain during urination.

"These symptoms could also be signs of other health problems, not related to cervical cancer." Wyand warned. "If you experience any of the symptoms above, talk to a health care provider." That cervical cancer is so difficult to detect is why women are recommended to get regularly screened through pap and HPV tests.

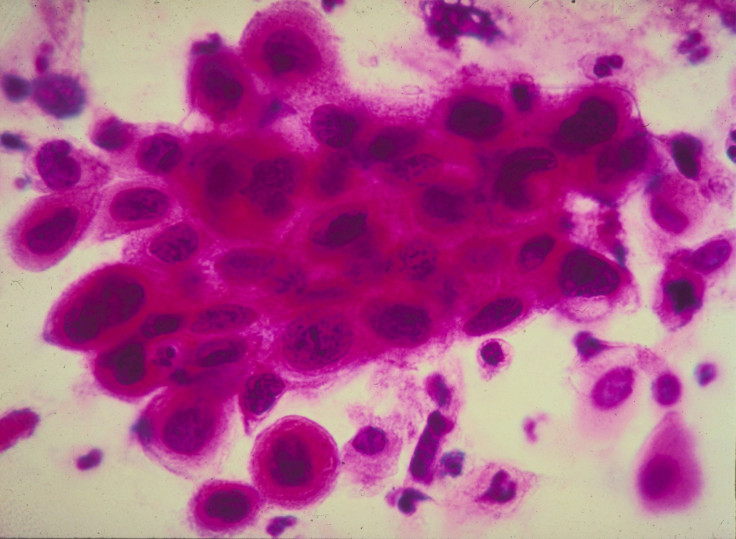

The pap test (smear), which only tests for cervical cancer and no other gynecologic cancer, collects cells from the surface of the cervix and vagina in order to identify abnormal cervical cells that can lead to cancer if left undetected, Wyand said. At this time your doctor can also choose to collect samples of fluid around the cervix to test for chlamydia and gonorrhea.

On the other hand, the HPV test is designed to detect only the virus; Wyand said it can detect any of the high-risk types of HPV most commonly found in cervical cancer. Both the pap and HPV test are typically done at the same "by using a small soft brush to collect cervical cells that are sent to the laboratory, or the HPV testing sample may be taken directly from the pap sample."

Right around here is where it starts to get tricky. It used to be that women turning 21 would make an appointment for a pap smear, and return each year until the age of 65. But guidelines under the Preventive Services Task Force suggests women get a pap smear every three years instead. According to a study published in Canadian Family Physician, this change has inadvertently led to a decrease in STD screening as well.

"Women suffer more frequent and serious complications from [STDs] than men," Wyand said. "These consequences can include pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic pain, and cancer. In fact, approximately 24,000 women become infertile each year from undiagnosed and untreated STDs."

In the latest CDC report on STDs, cases of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis have reached an all-time high in the U.S., and rising rates seem to be most prevalent for young people.

HPV Vaccines

HPV is the main cause of cervical cancer, as well as the leading sexually transmitted infection. The CDC found 80 million Americans are currently infected, and yet the uptake of the HPV vaccine in the U.S. is falling short of the Healthy People 2020 goal of 90 percent coverage.

Gardasil is a vaccine available for both males and females, Wyand said. Developed by Merck, data shows Gardasil "is close to 100 percent effective at preventing infection associated with low-risk types 6 and 11 (also types associated with 90 percent of all genital warts), as well as the aforementioned high-risk types, plus many anal, vulvar, and vaginal cancers."

This may be the vaccine series you hear about most, but it’s certainly not the only one. There are two other vaccines, one called Cervarix and Gardasil 9. Cervarix was made just for women, but boasts the same efficacy rate as the original Gardasil. The other major difference is it was made to protect against high-risk types of HPV.

As for Gardasil 9, a vaccine just approved in December 2014, it covers nine HPV types, Wyand said — "the two low-risk types that cause most cases of genital warts (HPV 6 and HPV 11) along with seven high-risk types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) found in a number of cancers, including about 90 percent of cervical cancers around the world as well as most anal, vulvar, and vaginal cancers."

The HPV vaccine is administered in three doses, the first of which the CDC suggests adolescents receive at either age 11 or 12 so young kids have a chance to build immunity before they become sexually active — a measure some don’t agree with.

Some people, largely anti-vaxxers, warn against the severe side effects of the HPV series, from increasing risk for multiple sclerosis to death. But Wyand hasn’t found this to be the case.

"Tested in thousands of people in many countries, both Gardasil and Cervarix have proven to be safe and well tolerated; the most common side effect has been soreness at the injection site," he said. "Virtually all [prescription] medications and/or vaccines on the market could possibly cause a serious problem, such as a severe allergic reaction. However, the risk of any vaccine causing a serious injury, or death, is extremely small."

Two states actually mandate young women get vaccinated — Virginia and Rhode Island — as well as Washington, D.C., according to KFF. Outside of the country, Australia launched an HPV vaccine program for women in 2007, and in 2014 for men. The vaccine is offered free in all schools at ages 12-13. Wyand said the program is currently associated "with large decreases in both genital warts and high-grade cervical precancer."

"They have much higher coverage than we do in the U.S. — 2014 data show about 73 percent coverage for females through age 15," he said. "2014 data from the U.S. show less than 40 percent of girls ages 13 to 17 have had all three doses."

Action Plan

It’s not just that women are weary of the vaccine; Wyand cited some women need more information and a proper provider recommendation. Providers themselves have noted barriers to HPV vaccines include concerned parents, costs, and also a disconnect on the need for male vaccination.

"Potential solutions include patient and provider outreach and education, of course," he continued. "Also reduce the ‘missed opportunities’ so that vaccines are offered as a normal part of the adolescent slate of immunizations."

To Wyand, HPV vaccines shouldn’t be treated as something different from other vaccines, or set aside with an asterisk. Instead, it’s just "what we do along with the others."

So during January, and every month after that, women should take full advantage of offered screenings and vaccines. Cervical cancer is preventable, and modern technology provides "a very real chance to eliminate certain types of cancer."

"The women most at risk are those who aren’t accessing these effective prevention tools," Wyand concluded, "so spreading the word and ensuring access are critical."

Published by Medicaldaily.com