Conspiracy Theories Still Thrive 50 Years After Kennedy Assassination: Psychologists Explain Why These Notions Stick

Does widespread belief in conspiracy theories exist today? According to a poll conducted by the Public Polling Policy (PPP) last spring, which asked 1,200 voters, the answer would be ‘yes’.

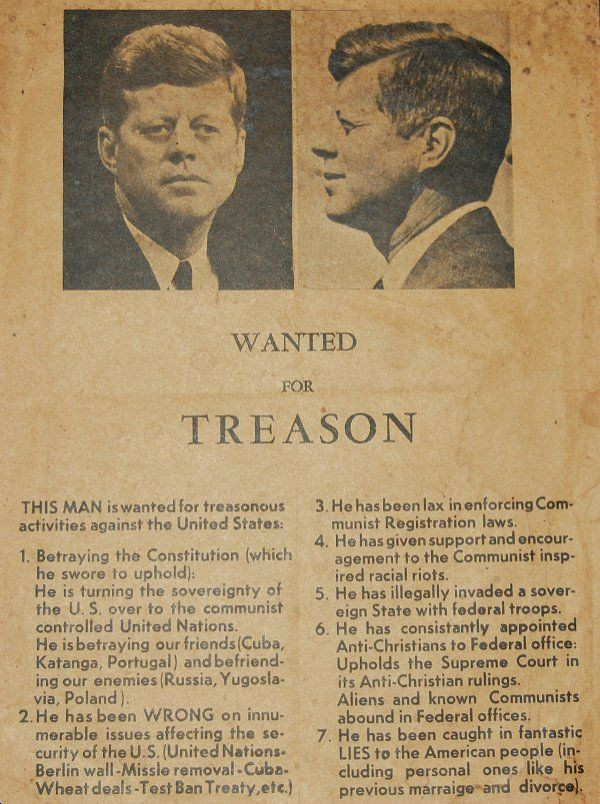

During the days leading up to President Kennedy’s fateful visit to Dallas 50 years ago, thousands of flyers were distributed around the city claiming that Kennedy was carrying out numerous acts of treason. The leaflet blamed Kennedy for “turning the sovereignty of the U.S. over to the communist controlled United Nations,” and giving “support and encouragement to the Communist inspired racial riots” among other things.

This handout seemed to reflect the mindset of many people in Dallas at the time. A mindset that then UN Ambassador, Adlai Stevenson, found when he encountered mass ire upon his visit to the city not long before Kennedy’s.

The PPP poll found that 28 percent of voters “believe that a secretive power elite with a globalist agenda is conspiring to eventually rule the world through an authoritarian world government, or, New World Order.” Over half of Americans (51 percent) apparently believe that there was a larger agenda being carried out in the JFK assassination, while 25 percent think Lee Harvey Oswald acted alone.

Unsurprisingly, conspiracy theory beliefs fall along political lines. When asked about global warming being a hoax, 58 percent of Republicans considered it a conspiracy, while 77 percent of Democrats disagreed with the statement. With regard to the Bush administration intentionally lying about weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, in order to justify the war, 72 percent who agreed with the statement were Democrat while 73 percent who disagreed were Republican.

Interestingly, the PPP poll found that voters who agreed with one conspiratorial statement were more likely to support other ones as well. A belief in the JFK assassination being an elaborate scheme often went hand-in-hand with thinking that a UFO crashed in Roswell in 1947, and that the CIA intentionally brought down city communities by introducing crack cocaine.

In a 2009 study about conspiracy theories, published in the Journal of Political Philosophy, Cass Sunstein and Adrian Vermeule explain that continually believing in plotted hidden agendas stems from a form of isolated echo-chamber effect. “Most people lack direct or personal information about the explanations for terrible events, and they are often tempted to attribute such events to some nefarious actor, in part because of their outrage,” they write. “The temptation is least likely to be resisted if others are making the same attributions.”

The authors added that conspiracy theories can be made impermeable by their “self-insulating quality”. They write: “The very statements and facts that might dissolve conspiracy cascades can be taken as further evidence on their behalf. These points make it especially difficult for outsiders, including governments, to debunk them.”

In other words, there is a catch-22 whereby refuting a conspiracy theory can end up further legitimizing them.

Stephan Lewandowsky, a University of Bristol psychologist who specializes in conspiracy theories, explained to Mother Jones that conspiracy theorizing is related to the psychological phenomenon of “motivated reasoning.”

In Mother Jones, writer Chris Mooney explains that this psychological process stems from how “people’s emotional investment in their ideas, identities, and worldviews bias their initial reading of evidence, and do so on a level prior to conscious thought.”

In his book, Kluge: The Haphazard Evolution of the Human Mind, New York University psychologist, Gary Marcus, argues that the human brain has evolved in such a way that makes us all vulnerable to being credulous to notions regardless of any evidence to the contrary.

Marcus defines motivation reasoning as our “tendency to scrutinize ideas more carefully if we don’t like them than if we do,” and views it as a complement to confirmation bias, which is “an automatic tendency to notice data that fit in with our beliefs.”

As a consequence, our minds are selectively open to notions that fall in line with certainties while being careful to reject ideas that challenge those convictions.

If you add our propensity to be influenced by irrelevant information to confirmation bias and motivated reasoning, “you wind up with a species prepared to believe, well, just about anything,” Marcus writes.