Domestic Violence Affects Boys And Girls Differently: Why One Reacts And The Other Recedes

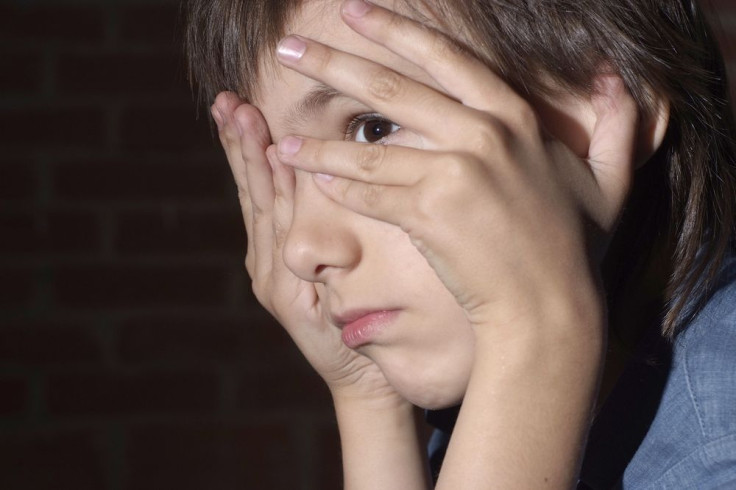

The quiet horror of intimate partner violence — physically aggressive acts between couples — sticks with kids for years. A new study finds it also sticks with them according to their gender, as many boys who witness their parents fighting tend to project their aggression outward, while girls keep their feelings inside and withdraw.

Mounting evidence in psychology research shows individual snapshots of kids’ behavior don’t capture the state of their mental health. A lot can happen between preschool and kindergarten — a turning point that can have dramatic impacts on a child’s academic performance and social skills. When parents fight, these turning points can turn to concrete parts of their personality.

“It’s this carryover effect,” Megan Holmes, assistant professor at Case Western University, told Medical Daily. Holmes is the lead author of the new study and an expert on domestic violence, particularly as it disrupts healthy childhood development. “Kids aren’t just affected when it’s immediately happening, but there is this chain effect that’s happening in the later years.”

In the latest investigation, Holmes and her colleagues looked at data on 1,125 children referred to Child Protective Services for abuse or neglect, whose cases were housed in a federal database. They tracked how often kids were exposed to male-led partner violence, including fathers and non-biological figures, and how kids’ behaviors shifted from preschool to kindergarten. While most children fell in the normal ranges for social development and aggression, in preschool 14 percent of kids showed aggressive tendencies and 46 percent lagged in social skill development. By kindergarten, aggressive tendencies had risen to 18 percent and social skill lags dropped to 34 percent.

Falling on traditional gender lines, boys and girls displayed varied responses to parental violence. Boys tended to mirror their fathers’ aggressive behaviors, becoming more verbally abusive and quick to turn on their peers. Girls, meanwhile, channeled their inner difficulties into their social skills. They had trouble interacting with other kids and became more anxious or depressed, Holmes says. “That may be why we’re not necessarily seeing the effect of aggressive behavior for girls.”

Looking at the big picture of childhood development isn’t all that new for Holmes. In 2013, she published a study describing a so-called “sleeper effect.” Again, investigating intimate partner violence, she found that kids who were exposed to the violence at an early age showed no behavioral effects directly after, but they seemed to lay dormant until the child reached school age. Then the sleeper effects re-emerged and played out as expected.

In both this study and the more recent one, she says, magnification with time is an all-too-prevalent factor. And while the data samples exclude violent mothers, much of the research into domestic violence already tilts the proportion heavily toward victims being female. Each year, roughly 1.3 million women experience physical assault by an intimate partner, making up approximately 85 percent of the total victim pool. Worse, when kids witness the behavior, they are more likely to adopt it themselves once they grow up.

Given these sleeper effects, Holmes says the best course of action is to curtail aggressive or antisocial behavior early. Moving from preschool to kindergarten isn’t just a matter of a birthday. It’s a big step from a classroom based on cultivating social skills to one focused on academics. It’s up to observant teachers and school officials, she says, to make sure the only baggage kids are carrying during that time are the school supplies on their backs.

Source: Holmes M, Voith L, Gromoske A. Lasting Effect of Intimate Partner Violence Exposure During Preschool on Aggressive Behavior and Prosocial Skills. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2014.

Published by Medicaldaily.com