Ebola Virus: Facts And Figures To Quell Your Fears

With the news of a possible case of Ebola virus in Canada, many people have begun to wonder, What is this disease? Can I catch it?

The Ebola virus is named after the Ebola river in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is near one of the first of two simultaneous outbreaks that occurred in 1976. Ebola virus causes severe viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF), according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Symptoms include sudden fever, intense weakness, muscle pain, headache, sore throat, vomiting, and diarrhea. A rash, containing blood, may appear over the patient's entire body as the eyes and genital become swollen. Next, a patient may develop kidney and liver impairment, and in some cases, begin to bleed both internally and externally. In some cases, patients bleed from their eyes, ears, and nose; often they bleed from the mouth and rectum. No vaccine or drug has been created to treat the virus. The fatality rate may rise as high as 90 percent of all who develop VHF.

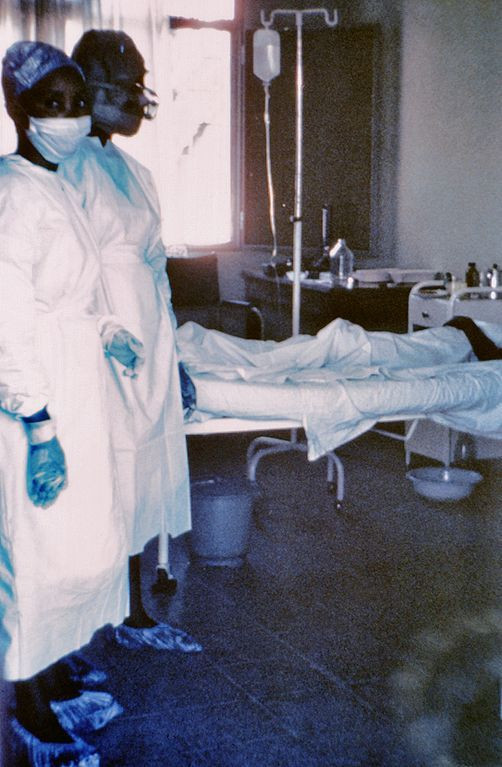

Outbreaks primarily occur near tropical rainforests in remote villages in Central and West Africa. There are five distinct species of Ebola virus: Bundibugyo, Ivory Coast, Reston, Sudan, and Zaire. These separate Ebola viruses are able to live in infected animal hosts, but humans can contract the viruses from animals. After this initial animal-human transmission, the viruses can spread from person to person through contact with body fluids, including blood and other secretions, or contaminated needles. (Health care workers have often become infected, according to the WHO.) The incubation period varies widely, as short as two days from first exposure to as long as 21 days. Worse, laboratory tests suggest that people may be infectious for up to 61 days after their symptoms begin. Because there is no real treatment, people diagnosed with Ebola virus generally are quarantined and then are treated for symptoms and complications, if possible.

Naturally, the case of the Canadian man who fell seriously ill after returning from a trip to West Africa, where a recent outbreak has already sickened over 80 people, sparked general fear. Over the weekend, Saskatchewan public health officials reported his symptoms strongly resembled a hemorrhagic fever. Today, the BBC reported that tests confirmed he does not have Ebola, while also clearing him of Marburg virus, Lassa fever, and Rift Valley fever. According to WHO, the man, who is still quarantined and in a critical condition, may be sick with a severe form of malaria.

Although his case of possible Ebola virus has been adequately disproven, some people have nevertheless begun to question their assumptions about disease and how diseases spread. It happened so fast. Aren't people traveling all over the world all the time? Why don't more people bring back strange illnesses with them? To answer these questions, it's important to think about disease generally.

Most of us unquestioningly think about disease as a simple contagion that somehow disrupts our body’s ability to function normally. Disease, though, may be better seen as an interaction between a host and a pathogen. For this reason, the way a disease affects one person may be radically different from how the same disease affects another. In addition, many factors influence the spread of infectious diseases, including the natural health and resistance of each individual who comes in contact with the pathogen causing it. For this reason, there may be natural barriers to certain diseases spread in areas of the world where most people are strong and healthy, while other areas of the world suffering from general poor health might be more susceptible.

Scientists understand, however, that a disease appearing even in the remotest area on Earth can spread anywhere within a day. And a new infectious disease may appear at any time. Perhaps the only possible form of self-protection is continuously strengthening your immune system by eating correctly and exercising.

Published by Medicaldaily.com