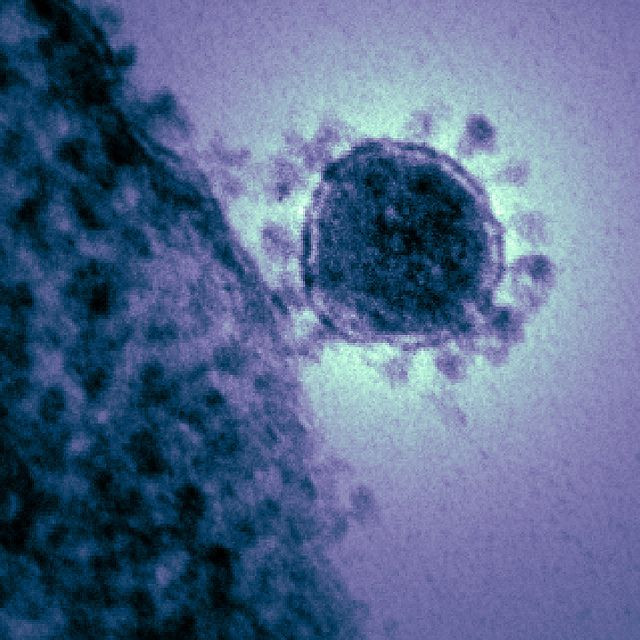

Engineered Strain Of MERS Coronavirus Could Serve As Basis For Vaccine; Mutated Strain Isn't Able To Infect Host

First reported in Saudi Arabia in June 2012, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) has already claimed 108 victims, of whom nearly half have died. The virus easily spreads from those who are ill to others with close contact, however, there may be a vaccine soon enough. Scientists at The Autonomous University of Madrid have engineered a strain of the virus that they say could serve as the basis for a safe and effective vaccine.

Luis Enjuanes, co-author of the study, which details the engineering of the strain, applied 30 years of experience in the molecular biology of coronaviruses to create an infectious clone of the MERS genome. They then combined the synthesized viral chromosome with a bacterial artificial chromosome, which allowed them to test different mutations on its genes. One gene at a time, they tested how mutations affected the virus’ ability to infect, replicate, and re-infect cultured human cells.

These tests showed that disabling accessory genes 3, 4a, 4b, and 5 (responsible for functions unessential to the organism’s replication, maintenance, or transfer), did nothing to stop the virus from growing at comparable rates to the normal MERS coronavirus. However, when they mutated the envelope protein (E protein), which is responsible for helping the virus enter hosts, they found that the virus could replicate its genetic material but it couldn’t infect nearby cells.

For a vaccine to work, the engineered MERS coronavirus would have to be able to grow — something it can’t do without the E protein. To grow, so-called “packaging cells” would be able to express the missing E protein in the virus. When these cells are injected with the engineered strain, genes within the cells’ chromosomes would encode the E protein while remaining separate from the viral genes of the engineered strain. “Therefore, in these cells, and only within them, the virus will grow by borrowing the E protein produced by the cell,” Enjuanes said in a statement.

“When the virus is administered to a person for vaccination, this person will not be able to provide the E protein to the defective virus,” and the virus will eventually die once the body’s immune system fights any antigens the virus produces.

Although a vaccination from this strain sounds promising, the missing E protein is only one safeguard that prevents the virus from growing. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires at least three safeguards for a recombinant live attenuated vaccine strain—a weakened virus used for vaccination — Enjuanes says, adding that more work remains before they can begin clinical trials.

Meanwhile, a therapy involving two anti-viral drugs to treat MERS coronavirus on lab monkeys was successful on Sunday. The two drugs, interferon-alpha 2b and ribavirin, are normally used together to treat hepatitis C. The drugs “should be considered as an early intervention therapy,” researchers wrote in the journal Nature Medicine, according to Fox News.

MERS coronavirus is a severe respiratory illness. It causes fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Although most cases of the infection have been in areas close to the Middle East, including Jordan, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia, its fatality rate and the way it spreads is what’s so alarming to public health officials.