Experimental Immunotherapy Treatment Has More Than 90% Remission Rate With Advanced Leukemia Patients

A experimental cancer treatment seems to have swung for the fences in its first early phase clinical trial — achieving a 90 percent complete remission rate in 28 surviving patients whose advanced leukemia had either relapsed or proven resistant to earlier therapy.

The findings were published Monday in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

"In early-phase trials, you're continually learning. You don't expect results like these from early-phase trials,” said senior author Dr. David Maloney of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle in a statement. "That's why these response rates are so extraordinary."

The treatment is the latest example of a still-developing field of cancer medicine known as immunotherapy, which attempts to manipulate a person’s immune system into directly fighting off cancer cells through a variety of different methods.

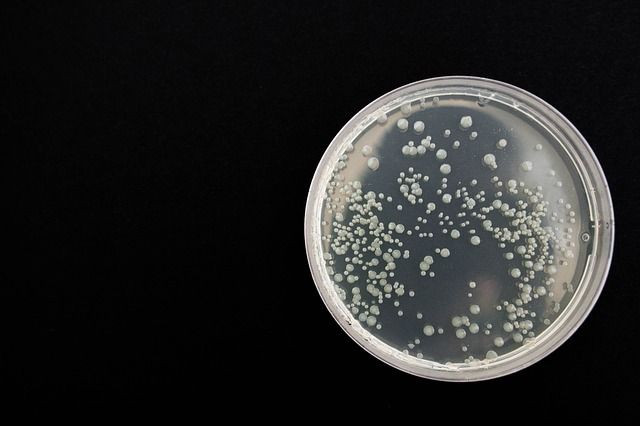

A potential avenue of immunotherapy has been to genetically engineer T-cells, one of the immune system’s primary lines of defense, to express an artificially designed protein known as a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR). Researchers take the T-cells out of the patients, modify them with the help of a virus, and reproduce them in the lab before reintroducing them to the patients. If these CAR T-cells are successfully accepted by the body and continue to multiply, they’ll be able to eradicate tumor cells that possess whatever specific antigens the researchers designed them to attack.

In this latest study, Maloney and his colleagues created CAR T-cells that would target an antigen commonly seen in leukemia cells, CD19, and gave them to 30 patients with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an especially fast-spreading and difficult to treat form of leukemia. While previous studies have used CAR T-cells to treat leukemia patients, this experiment took things one step further. T-cells can be broadly broken down into two major types — killer and helper — that work together to take down most threats to our body. Previous CAR experiments infused patients with whichever T-cells they could collect from them, but Maloney’s team made sure to give their group an even mix of both types. By combining the T-cells at a specific ratio, the researchers hoped to either boost the therapy’s effectiveness or at least better determine how it influenced the patient’s immune system.

“You can’t work out how to go forward if you don’t have any correlations between what you put into the patient and what happens to the patient,” lead author Dr. Cameron Turtle said in an accompanying news release produced by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. “If there’s an element of random effect in the dose of the stuff you’re giving or other things you’re doing, it’s very hard to make improvements.”

Remarkable as the findings are, they aren’t a miracle cure, at least not yet. Nearly all the patients suffered a side effect known as cytokine release syndrome, which triggers a severe and sometimes fatal inflammatory response throughout the body. Indeed, two patients died as a result of the therapy, one immediately after the infusion and the second after 122 days. As a result of the deaths, the researchers treated future patients with a lower dosage, which seemed to prevent any further severe complications.

And while the leukemia did appear to enter complete remission in 27 patients, it eventually returned with a fury for several patients. At least two developed a form of the cancer that contained no CD19 antigens, making any further attempts with this treatment fruitless. The bodies of the rest of the patients who relapsed proved resistant to additional infusions of the CAR T-cells.

These hurdles will take time and more research to overcome, though Turtle and his team are eager to take them on. "This is just the beginning," he said. "It sounds fantastic to say that we get over 90 percent remissions, but there's so much more work to do make sure they're durable remissions, to work out who's going to benefit the most, and extend this work to other diseases."

Source: Turtle C, Hanafi L-A, Berger C, et al. CD19 CAR–T Cells of Defined CD4+:CD8+ Composition in Adult B Cell ALL Patients. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2016.