Eye Exams May Predict Future Mental Decline

The retina at the back of the eye may offer insight into the health of the brain, according to a new study.

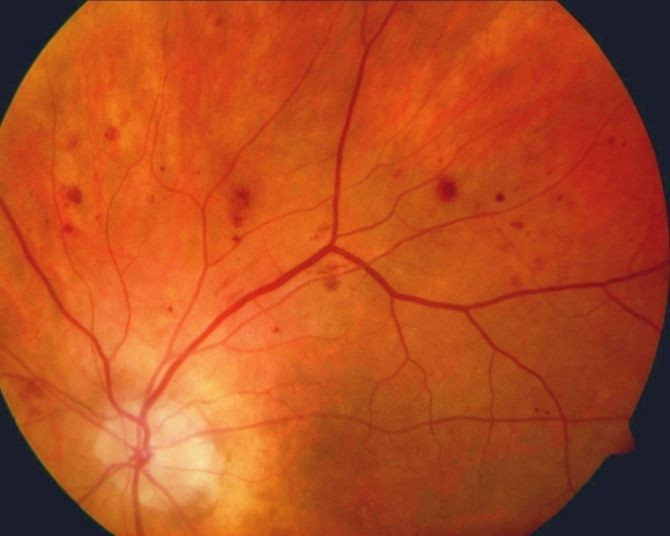

Researchers found that even people with minimal damage to blood vessels in the retina have a higher chance of cognitive decline because poor blood supply that affects the eye may also be affecting the brain.

Patients with retinopathy, a common condition often caused by Type II diabetes and uncontrolled high blood pressure and the leading cause of blindness among U.S. adults, may have a higher risk for memory and thinking declines, according to researchers at the University of California in San Francisco.

Researchers examined data from a large study called the Women’s Health Initiative that consisted of 511 women with an average starting age of 69 who were followed for 10 years. Each year the women had taken a cognition test measuring memory and thinking processes, and they had all received two eye exams to assess their eye health during the fourth and brain health in the eighth year of the study.

Researchers found that 7.6 percent of the women had retinopathy, and while their vision was not significantly worse than women without the disease, these women had significantly lower average scores on memory and thinking tests. Brain scans had also revealed that they had more blood vessel damage in their brains.

Women with retinopathy had more ischemic lesions and damaged brain tissue than women without the condition.

Researchers suggest that a simple eye exam could serve as a marker for future cognitive changes related to vascular disease, and may allow early diagnosis and treatment to reduce the progression of cognitive decline to dementia.

"Lots of people who are pre-diabetic or pre-hypertensive develop retinopathy," said the lead author of the study Dr. Mary Haan, professor of epidemiology and biostatistics, in a news release on Thursday. "Early intervention might reduce the progression to full onset diabetes or hypertension."

Researchers noted that there was only a small proportion of patients with retinopathy in their study, and larger studies are required to confirm that their findings could be used as a clinical test for declining cognitive function.

They noted that while there was no evidence suggesting dementia in any of the patients, brain decline is an early sign of the disease.

“As the authors point out, there was a decline in cognitive performance before retinopathy was evaluated. It is certainly possible that those individuals with retinopathy would have been identified as having retinopathy had they been evaluated sooner, but the strongest clinical utility of retinopathy evaluation would be if it clearly identified individuals before they developed cognitive decline,” Dr. Rebecca Gottesman of Johns Hopkins Medicine said in an accompanying editorial.

“Treatments for dementing illnesses, when they become available, are most likely to be of benefit in individuals in the preclinical stage of the disease, and markers that identify those at risk for subsequent cognitive decline are most critical. Although this emphasis on preclinical biomarkers is primarily a concern for neurodegenerative dementias such as Alzheimer disease, it is also relevant for cerebrovascular disease,” Gottesman added.