FDA Approves Obesity Treatment Device Designed To Kill Hunger Signal Between Brain And Stomach

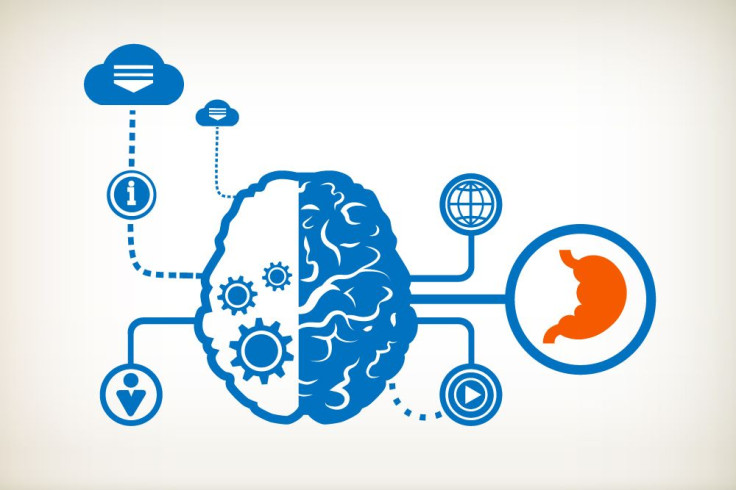

Obesity is finally being treated like a disease now that the Food and Drug Administration has approved a device to virtually stop hunger. The Masetro Rechargeable System is the first of its kind and was designed to treat obesity by cutting off the signal between the brain and stomach with electrical impulses. The FDA announced it was designed to help obese adults lose weight and decrease their risk of developing an obesity-related condition, such as heart disease.

The medical device, surgically implanted into the abdomen, works by shocking the abdomen’s vagus nerve, which tells the brain if the stomach is empty or full. The electrical stimulation emitted from the implanted device blocks the message the stomach tries to send to the brain, so “I’m hungry” never makes it to the brain. The long-term goal is to treat obesity, metabolic diseases, and even gastrointestinal disorders. There are already a variety of pills on the market intended to curb hunger and treat obesity, but none include a device with a battery-charged remote like this one.

“Obesity and its related medical conditions are major public health problems,” Dr. William Maisel, deputy director for science and chief scientist in the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a press release. “Medical devices can help physicians and patients to develop comprehensive obesity treatment plans.”

Researchers studied 233 patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 35 or higher and implanted the device into 157 of them. A person’s BMI is calculated based on his weight and height, and is often seen as controversial among the medical community. However, a BMI of 30 or greater is considered obese, meaning those used in the study have far exceeded the weight of a healthy “normal” weight.

Within a year, patients who used the Maestro device lost 8.5 percent more weight than the 76 patients who didn’t use the device as intended. What’s even more encouraging about the results are about half of the patients using the device lost at least 20 percent of their excess weight, and another 38.3 percent of the patients lost at least 25 percent of their excess weight. At first, it may sound strange to treat an obese person's weight with a device, but its innovative approach can be likened to a pacemaker, which may have also seemed like a precocious step in medicine when it was first introduced over 60 years ago.

Finally Treating Obesity As A Disease

This device has the potential to go a long way in a country with 78.6 million obese adults. That’s more than one-third of the nation, and with it comes a laundry list of obesity-related conditions. Being obese puts a person at risk for heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes, certain types of cancer, high cholesterol and blood pressure, infertility, sleep apnea, and more, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Treating obesity is not just about improving the quality and quantity of life, but also relieving some of the burdening medical costs. An obese person’s medical costs were $1,429 higher than the costs for a person of normal, healthy weight in 2008. In 2013, the American Medical Association voted to officially recognize obesity as a disease in order to change the way physicians, society, and the obese think about this life-threatening health condition.

“I think you will probably see from this physicians taking obesity more seriously, counseling their patients about it,” Morgan Downey, an advocate for obese people and publisher of the online Downey Obesity Report, said after the AMA made its decision. “Companies marketing the products will be able to take this to physicians and point to it and say, ‘Look, the mother ship has now recognized obesity as a disease.’”

FDA Approving The First Of Its Kind

The device has had to jump through a lot of hoops to get approval. Stockholders even revealed their concern when stocks dropped in 2013, while EnteroMedics were in the process of working with the FDA. Originally, the researchers wanted to see the group that used the device lose at least 10 percent more excess weight than the other group. The experiment continued for a total of 18 months, but they still didn’t achieve the goals they originally set out for.

“We are very encouraged by the responsiveness of the FDA and are confident in our ability to address their questions in a timely manner,” EnteroMedics’ President and Chief Executive Officer Mark B. Knudson said in a press release of filings from 2013. “We will continue to work closely with the FDA throughout this process. We believe that the Company continues on track for a panel in late Q4 2013/Q1 2014 with approval decision in the first half of 2014.”

The FDA Advisory Committee eventually decided because the device kept the weight off and had more benefits than risks, it was worth releasing onto the market. However, as part of the deal the EnteroMedics must conduct a five-year post approval study that will include at least 100 patients to see how the device functions in the “real world.” The FDA will require them to provide additional information on weight loss, adverse effects, surgical revisions or possible removals. Currently, the only adverse events that have been reported from the clinical study included nausea, heartburn, problems swallowing, chest pain, pain at the implant site, vomiting, and surgical complications. Any surgery performed on an obese person automatically puts him at risk for surgical complications.