A-Fib Patients Face Increased Dementia Risk If Blood-Thinning Medication Not Dosed Correctly

Patients suffering from atrial fibrillation, or more commonly known as “A-fib,” may face a heightened risk for dementia if the dosing range for their blood-thinning medication is too high or too low, a new study finds.

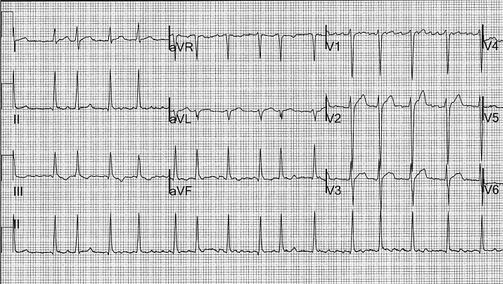

Due to the nature of A-fib’s arrhythmia — meaning the heart’s irregular beat pattern, disrupting consistent blood flow — sufferers must often take anticoagulant medication that lowers their risk for stroke. But according to the new study, incorrect dosage can lead to alternate consequences: clotting if the doses are too low, and bleeding if they are too high. While the exact mechanism for upping dementia’s risk is unknown, researchers believe these errors may contribute a large portion.

“The most common anticoagulant used worldwide is warfarin, and we now know that if warfarin doses are consistently too high or too low, one of the long-term consequences can be brain damage," said Dr. Jared Bunch, lead author and director of electrophysiology research at the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute, in a statement.

Bunch and his colleagues combed through the medical records of more than 2,600 A-fib patients to assess their dementia risk. What they found was that frequency of improper dosing directly related to the chances a person would suffer from dementia. For example, someone whose medication was right only 25 percent of the time faced a 4.5-times greater risk than someone who took the correct amount 100 percent of the time. That risk dropped as frequency increased. Overall, the risk for dementia was about 4.1 percent.

Nearly 10 percent of the U.S. population will suffer from atrial fibrillation at some point in their lives, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The real number is somewhere around 2.7million, and the CDC reports that by 2050 it will have risen to as many as 12 million. Characterized by a jumpy, irregular heartbeat, A-fib is the most common form of heart arrhythmia in the world. Its causes can range from alcohol use and hypertension to heart attack and coronary artery disease.

As Bunch describes, warfarin is the most popular anticoagulant used to counteract the clotting that can result from A-fib. However, the current study raises concerns over how often warfarin is correctly dosed to patients, given the tenuous balance between a dosage being harmful or appropriate. When warfarin is first prescribed, physicians take into account age, body size, smoking habits, and other medications the patient may use. Prescribing too strong a dosage could result in disruption of those other meds.

“Patients on warfarin need very close follow-up in specialized anticoagulation centers if possible to ensure their blood levels are within the recommended levels more often,” Bunch explained. "Second, these results also point to a potential new long-term consequence of dependency on long-term anticoagulation medications.”

Avoiding the risk for dementia is of particular concern, prior research suggests, as the overall rate is slated to triple by 2050. This is partly due to the fact people are simply living longer. In decades past, when disease would wipe out adult populations before their 70th birthday, people weren’t living long enough to be exposed to mental health risks. Now that modern medicine can keep people alive past the 100-year mark, brain diseases are emerging in troubling numbers.

However, even with the risk presented by incorrect A-fib dosing, chief executive of Alzheimer’s Research UK believes there isn’t a reason to panic. “An intervention to delay the onset of Alzheimer's by five years,” she told reporters in Dec. of 2013, “could halve the number of people who die with the disease, having a transformative impact on millions of people's lives.”

Researchers from the Intermountain Medical Center Heart Institute will present the findings of their study at the 2014 Annual Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Session on Friday, May 9, in San Francisco.