Genetics And Neurobiology: The Future Of Bipolar Disorder Treatment And Diagnosis

Patients with bipolar disorder experience recurrent episodes of mood disturbance, ranging from extreme elation (mania) to severe depression. The disorder is thought to affect roughly 2 percent of the world's population in its most pronounced forms (bipolar I and II), with milder forms of the disorder affecting another 2 percent.

Today, The Lancet has published a new series of three papers that examine the genetics, diagnosis, and treatment of bipolar disorder. The authors outlined future challenges and debated imminent changes to the criteria for diagnosis of the illness, along with additional commentary assessing proposals for mental disorders specifically associated with stress in the International Classification of Diseases-11.

"Bipolar disorder is not just about the extremes of emotion: it is also about the individual who exists both at, and between, those extremes," wrote the series' editors. "The psychiatrist of the future must be able to ally human and scientific understanding; to collaborate meaningfully and respectfully with patients in planning care; and to be confident and pragmatic, but receptive to new discoveries that may challenge the very basis of his or her understanding of mental illness."

Series Paper One

Bipolar disorder is currently diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms, such as alternating periods of depression and mania. The contribution of environmental and social factors toward an individual's risk of developing bipolar disorder should not be underestimated, yet studies of families and twins show the importance of genetic factors affecting susceptibility to bipolar disorder. Scientists' growing knowledge of the contribution of genetics to bipolar disorder nonetheless leads to the tantalizing possibility that scientists might be on the verge of being able to identify some of the biological systems that lead to illness in bipolar disorder, which could in turn lead to substantial improvements in diagnosis and treatment of the illness.

"The association between genotype and phenotype for psychiatric disorders is clearly complex," wrote Professor Nick Craddock, one of the paper's authors. "The key point is that most cases of bipolar disorder involve the interplay of several genes or more complex genetic mechanisms, together with the effects of the environment, and chance."

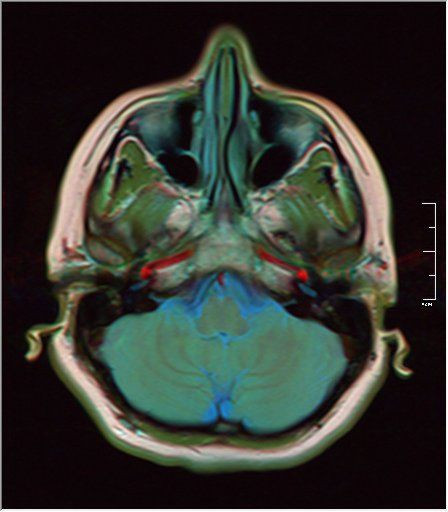

The authors emphasized that bipolar disorder research now needs to follow up genetic studies with imaging and psychological studies in order to try and unravel the complex biological mechanisms involved in bipolar disorder, and bring biological understanding closer to the experience of the patient.

Series Paper Two

Substantial difficulties complicate the diagnosis of bipolar disorder, which refers to a group of affective disorders. These affective disorders include bipolar disorder type I (depressive and manic episodes: this disorder can be diagnosed on the basis of one manic episode), bipolar disorder type II (depressive and hypomanic episodes), cyclothymic disorder (hypomanic and depressive symptoms that do not meet criteria for depressive episodes), and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (depressive and hypomanic-like symptoms that do not meet the diagnostic criteria for any of the aforementioned disorders).

Depressive symptoms are considerably more prevalent than manic symptoms over the course of the illness for most people with bipolar disorder, and people are more likely to seek treatment for depressive symptoms. There is an average delay of five to 10 years between the onset of bipolar disorder and diagnosis, and misdiagnosis of the disorder as unipolar depression is common. Most importantly, the medicine for unipolar depression could exacerbate the manic symptoms.

"Identifying objective biomarkers that differ between bipolar and unipolar depression would not only lead to more accurate diagnosis but potentially to new, personalized treatments, yet very little research has been undertaken in this area," said Professor Mary Phillips, one of the paper's authors. "For instance, very few neuroimaging studies have been done in which the brains of people with bipolar disorder have been compared to those of people with unipolar disorder, and further research into this area is urgently needed."

The authors further suggested that innovative combinations of neuroimaging and pattern recognition approaches might better identify individual patterns of neural structure and function that accurately diagnose a patient's precise affective disorder.

Series Paper Three

Lithium, first introduced in 1949, remains the best long-term treatment for bipolar disorder, but its benefits are restricted and alternatives are often needed for lengthy treatment. There have been no fundamental advances in the search for more effective treatment for bipolar disorder in the last 20 years. "Combining psychosocial treatments - which can include not just psychotherapy for the patient, but family therapy involving education for their family or caregiver - with mood stabilising drugs might well be one of the most promising lines of treatment for bipolar disorder," said Professor John Geddes, one of the paper's authors.

Treating bipolar is complex because the same treatments that alleviate depression can cause mania or mood swings, and treatments that reduce mania may cause rebound depressive episodes. The development of future treatments should consider both the neurobiological and psychosocial mechanisms underlying the disorder. "Drug and psychological treatment studies have largely proceeded independently of one another, and research including both would help to move the field forward," said Geddes.

Additional Commentary

The World Health Organization is currently developing the International Classification of Diseases, version 11 (ICD-11), a comprehensive, internationally-recognized diagnostic guide for all major diseases, including psychiatric illness. Members of the ICD-11 Working Group outline the reasoning behind some of the updates, including a substantial tightening of the description of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and the addition of "complex PTSD" and inclusion of "prolonged grief disorder."

An updated version of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is due to appear this month. Professor Gin Malhi of the University of Sydney, Australia, expressed concern that the inclusion of a "mixed states specifier" in the criteria for bipolar disorder may lead to diagnostic confusion, and complicate treatment implications.

The Lancet. 2013; 381:9878, p 1597-1686. http://www.thelancet.com/themed/bipolar-disorder. Accessed May 10, 2013.

Published by Medicaldaily.com