A 'Grenade' For Killing Cancer Uses Heat To Target Cells, Release Cancer-Fighting Drugs

Normally, grenades are bad for your health. They explode, spreading shrapnel and other incendiaries into a thousand different directions, with only one purpose: causing maximum harm to anyone unlucky enough to be within the blasts’ radius. Fortunately, the grenade we’re talking about today does more good than bad, as it targets and kills cancer tumors.

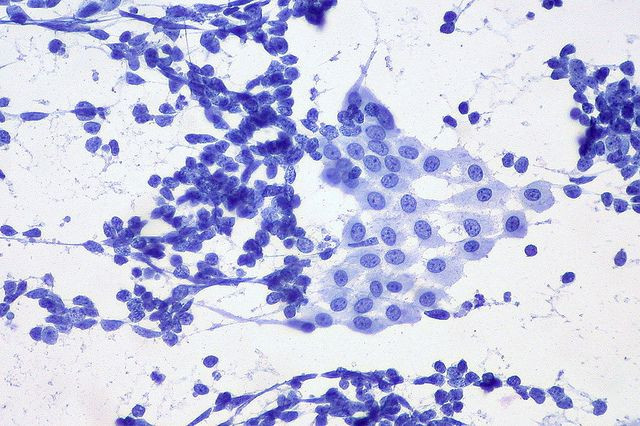

Researchers from the University of Manchester will present two studies at the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI) Cancer Conference in Liverpool that describe cancer drug-packed “grenades” with heat-sensitive triggers that allow for the direct treatment of cancerous tumors. The “grenades” are actually liposomes — small, bubble-like structures built out of cell membrane — and they’re used as packages to deliver drugs into the cancer cells. The challenge the researchers faced was being able to target tumors with the cancer drug-carrying liposomes, while also keeping healthy tissue intact.

The two studies show how the team managed to clear this hurdle by giving the liposomes heat-activated triggers. Testing the liposomes in a cell culture and lab mice, the team found that by slightly heating the tumors with warm water baths and heating pads, it was able to pinpoint the exact place where cancer resided — the “grenades” could then detonate and release the drugs.

"Temperature-sensitive liposomes have the potential to travel safely around the body while carrying your cancer drug of choice," said Kostas Kostarelos, study author and professor of nanomedicine at the University of Manchester, in a press release. "Once they reach a 'hotspot' of warmed-up cancer cells, the pin is effectively pulled and the drugs are released. This allows us to more effectively transport drugs to tumors, and should reduce collateral damage to healthy cells."

The researchers set the thermal triggers of the liposomes to 42 degrees Celsius (107 degrees Fahrenheit), which is slightly higher than normal body temperature. But, according to Kostarelos, “this work has only been done in the lab so far; [however], there are a number of ways we could potentially heat cancer cells in patients — depending on the tumor type — some of which are already in clinical use."

These studies open up a "range of new treatment avenues," said Professor Charles Swanton, chair of the 2015 NCRI Cancer Conference, in the press release. "This is still early work, but these liposomes could be an effective way of targeting treatment toward cancer cells while leaving healthy cells unharmed."

Source: Kostarelos K, et al. National Cancer Research Institute Cancer Conference. 2015.