Heart Transplant Breakthrough Revives Dead Organ Before Giving Patient New Life

A team of Australian scientists made history Friday when they announced success in reviving dead hearts and transplanting them from cadavers into awaiting patients. The operation was a success in large part because of the perfusion-based machine that re-animated the still organs.

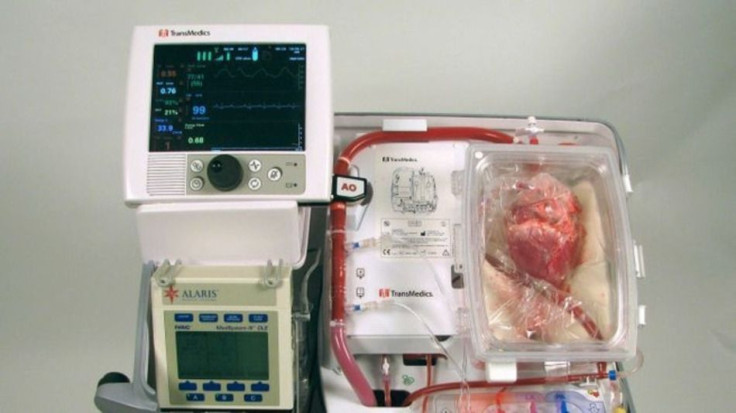

Doctors from St. Vincent Hospital in Sydney say the hearts had stopped beating for a full 20 minutes before they resuscitated them and installed them inside a machine that supplies the non-beating heart with steady supplies of oxygen, which they’ve dubbed the “heart in a box.” The team estimates the new method, one that has been in development for over 12 years, could potentially save 20 to 30 percent more lives.

Perfusion isn’t a new concept. There’s a good chance if you’ve ever needed the help of an EMT, part of the checklist in measuring your vital signs was seeing how fast the capillaries under your skin refilled with blood, going from white to pink. This replenishing is the perfusion. And it’s what makes transplanting a dead heart possible in the first place.

After the heart gets back up and running inside the machine, branded by TransMedics as OCS HEART, doctors remove the organ and inject it with a preservation solution, designed to keep the heart fresh, essentially, as it makes a new home in the patient’s body. “So those two things coming together [the console and preservation solution] almost like a perfect storm, have allowed this sort of transplantation of a heart that's stopped beating to occur," Professor Bob Graham told ABC News. Graham is the executive director of the Victor Chang Institute, the facility behind the preservation solution. “Before that it wasn't possible.”

In a world first surgeons at St Vincent's have transplanted a heart that had stopped beating .#9NewsAt6 pic.twitter.com/sIU1oRUI34

- Mark Burrows (@MarkWBurrows) October 23, 2014The breakthrough comes just over a year after another world-first, when transplant specialists at University Hospitals Leuven, in Belgium, performed a double transplant that involved a patient’s lungs and liver. In performing a routine lung transplant, doctors noticed acute liver problems. The patient then slipped into a coma, forcing doctors to remove the lungs and then the liver, because a liver transplant requires a healthy set of lungs.

But instead of putting the lungs on ice, as common practice would dictate, they turned to OCS LUNG — the same (and only) perfusion-based machine capable of keeping the organs alive. On ice, they would last no more than six hours. Inside OCS LUNG, they stayed healthy for 11 hours.

Over in Sydney, the most recent patient marks the third success story within a few months. The first was a 57-year-old woman named Michelle Gribilas, who was bedridden before the surgery but now says she feels like she’s in her 40s. The second was Jan Damen, a 44-year-old father of three. And the third, and most recent, patient is still recovering.

Though the perfusion-based technology is commercially available only in Europe and Australia, where it’s also being used in clinical settings, doctors say the technology is under investigation in the United States. In the meantime, the Victor Change Institute said in a statement that the breakthrough represents “a paradigm shift in organ donation” and has the potential to “result in a major increase in the pool of hearts available for transplantation.”